Out of the Furnace fueled by fiery performances

Every encounter with meth head mountain man Harlan DeGroat (Woody Harrelson) constitutes a near-death experience. From his death’s head grin to his ice-cold stare and Vesuvian temper, Harlan is the stuff of Ned Beatty’s post-Deliverance nightmares, a man-shaped monster with a sadistic streak a mile wide and a low animal cunning worthy of Charles Manson.

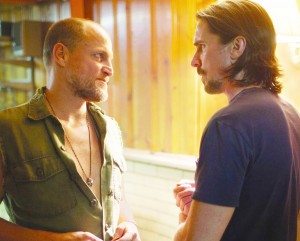

Family business · Woody Harrelson (left) is Harlan DeGroat, a cunning meth-addicted mountain man with a volcanic temper. Harrleson’s performance as DeGroat is his best since 1994’s Natural Born Killers. – Photo courtesy of Relativity Media

He’s also the best part of Scott Cooper’s Out of the Furnace, an overgrown genre picture galvanized by powerfully realized performances and a believably gritty depiction of a dying Rust Belt town and the poor souls doomed to inhabit it. The film, Cooper’s sophomore effort after casting Jeff Bridges as a whisky-clogged country troubadour in Crazy Heart, stars Christian Bale as Russell Baze, a steel mill welder struggling to keep his kid brother Rodney (Casey Affleck) out of trouble following the latter’s return from his fourth tour of duty in Iraq.

Haunted by the things he’s seen and done for his country, Rodney finds that he is unable to hold down a regular job, instead drifting further and further into the world of underground street fighting, numbing his mental and spiritual anguish with regular doses of physical punishment. After weeks of continually hounding his manager/loan shark Petty (Willem Dafoe) for bigger fights and better opponents, Petty grudgingly introduces the angry young man to Harlan, the mad-dog Appalachian bruiser who runs the New Jersey chapter of the fight club when he’s not tending to his own burgeoning meth empire. When Rodney fails to return home after a particularly brutal match, it falls to Russell to seek justice.

The success of Out of the Furnace hinges on the fraternal bond between Bale and Affleck’s characters, and both are tragically convincing as siblings who have seen more than their fair share of heartache and strife.

Bale’s Russell is older but only marginally wiser. After finishing a stint in prison for a manslaughter charge that cost him both his longtime girlfriend (Zoe Saldana, underused save for one devastating scene on a bridge) and his last chance to pull his brother back from the abyss, Russell is slaving away in the same mill that gave their father cancer. Meanwhile, Affleck’s Rodney is dead behind the eyes, a walking corpse who plans to atone for his sins by living out his days as little more than a human pitbull.

For a story so unrelentingly bleak, there are also moments of startling visual beauty, most of them having to do with the on-location setting of Braddock, Pa., where even the farthest horizon is dotted with erupting smokestacks and lined with the molten glow of steel mills. It’s a harsh, unforgiving landscape, one that wouldn’t be out of place in a John Hillcoat movie, but its decaying grandeur gives the viewer a sense of admiration for the hardworking men and women who still dare to live there. In many ways, Out of the Furnace is a western, and cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi (The Grey, Silver Linings Playbook) frames every shot like he’s filming in Monument Valley, especially during the operatic final act, which sees Russell transform from blue-collar schmoe to avenging angel.

The film also benefits from a supporting cast that seems curiously overqualified, especially given that most of their roles are little more than Screenwriting 101 archetypes. Dafoe succeeds in adding a few paternal wrinkles to Petty the Fixer, while Forest Whitaker radiates noble frustration as an honest cop who admits that there are certain pockets of Appalachia that exist beyond the realm of traditional law enforcement. Perennial bad-ss Sam Shepherd meanwhile legitimizes every scene he appears in as Russell and Rodney’s pistol-packing Uncle Red-— even if the character hews a bit too close to the riverfront hermit he played in last spring’s far-superior Mud.

It’s Harrelson, however, whose presence haunts every frame of Out of the Furnace. Sure, deranged hillbilly characters are a dime a dozen, but Harlan DeGroat is an exceptionally nasty piece of work, a frothing-at-the-mouth lunatic who seems to have the devil’s luck for never getting caught.

The scene in which he attempts to act human in front of Affleck and Dafoe is almost more chilling than the casualness of his later bloodletting. This is unquestionably the actor’s finest work since Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers: a potent, terrifying reminder of his range as a performer, especially for viewers who only know him as the lovable drunk Haymitch Abernathy in The Hunger Games. Long after the rest of Cooper’s film has receded from your memory, Harlan DeGroat will still be there. And he’ll be smiling that death’s head grin of his.

Follow us on Twitter @dailytrojan