Nick Cave and the mythology of the rock star onscreen

From the ferocious Birthday Party concerts of the 1970s and ’80s to the release of last year’s soothingly sorrowful Bad Seeds album Push the Sky Away, Nick Cave has always been an artist whose work defies easy categorization.

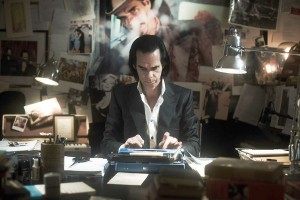

Cave man · The new film 20,000 Days on Earth presents a fictionalized day in the life of post-punk musician Nick Cave. It deliberately plays with fan expectations creating an artisitic whirlwind of a film. – Photo courtesy of Drafthouse Films

The Australian rocker’s fearsome appearance — think Elvis Presley reincarnated as a fire-breathing, Goth-punk troubadour with a voice so deep it’s practically bottomless — belies an incredibly eclectic range of influences: the puckish poetry of Leonard Cohen, the soul-baring ballads of Nina Simone, the death-haunted last testaments of Johnny Cash. His lyrics suffused with a heady brew of the sacred and profane, Nick Cave can transform himself from lecherous lounge lizard to sulfur-tongued preacher over the course of a single song.

Cave, a notoriously elusive presence offstage, would at first seem an unlikely subject for a documentary. Thankfully, the new film 20,000 Days on Earth, now playing in select theaters, isn’t interested in simply venerating him, dissecting his creative process or even peering into his private life as a family man and recovering heroin addict. Instead, the movie, helmed by first-time feature directors Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard and featuring scenes scripted by Cave himself, ambitiously blends fact and fiction to form a freewheeling, hallucinatory account of the musician’s twenty-thousandth day of life, the same day he began recording Push the Sky Away. The end result is simultaneously an extension of Cave’s own self-styled mythology, a daring exploration of the limits of artistic control and a fluid meditation on memory’s ability to imbue existence with the semblance of meaning.

While 20,000 Days on Earth’s approach is certainly unique, it’s hardly the first documentary to use the power of cinema as a way to inflate the legend of a particular musician. Richard Lester’s 1964 classic A Hard Day’s Night purported to be an average week in the lives of the Beatles, following the Fab Four from their hometown of Liverpool to a televised gig in London. Released at the height of Beatlemania, the movie was responsible for popularizing the character traits of the group’s individual members — Paul is the cute one! Ringo is the funny one! — and continues to influence the way certain bands are packaged to this day. The most memorable element, aside from the songs of course, is Paul’s “very clean” fictional grandfather, played by Irish character actor Wilfrid Brambell.

D.A. Pennebaker’s Dont Look Back [sic], arguably the first true “rockumentary,” followed Bob Dylan on his 1965 U.K. concert tour and featured a raw, unfiltered look at the legend in his cool, charismatic prime, as well as his occasionally fraught interactions with then-girlfriend Joan Baez, former Animals keyboardist Alan Price, fellow folk singer Donovan (his friendly competition with Dylan is a powerful reminder of the difference between talent and genius) and a small army of hangers-on. The film is also notable for its iconic opening scene, which finds Dylan crafting the music video for “Subterranean Homesick Blues” — the earliest of its kind — with the aid of Beat generation guru Allen Ginsberg and several dozen cue cards. Today Dont Look Back is rightly considered the benchmark by which all other rock docs are forever judged.

Other documentaries have been far less kind to their subjects, choosing instead to wallow in the pettiness and jealousy the rock star lifestyle often breeds. Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s Metallica: Some Kind of Monster revolves around the members of Metallica in the turbulent months leading up to the release of their 2003 album St. Anger. The movie is a fascinatingly candid depiction of a once great band brought low by a toxic combination of in-fighting and creative exhaustion in the wake of the abrupt departure of bassist Jason Newsted and lead singer James Hetfield’s struggles with alcoholism.

20,000 Days on Earth, which won awards for directing and editing at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, deliberately plays with audience expectations for this type of movie, interspersing Push the Sky Away rehearsal footage with enigmatic conversations about weather diaries and ghostly visitations from the likes of actor Ray Winstone and pop star Kylie Minogue, the latter of whom collaborated with Cave on the 1995 hit “Where the Wild Roses Grow.”

All these esoteric nods make sense when you consider the musician’s previous dalliances with film. In addition to a wonderfully weird cameo in Wim Wenders’s Wings of Desire and composing the original scores for John Hillcoat’s The Road and Andrew Dominik’s The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford with his Bad Seeds bandmate Warren Ellis, the multitalented Cave also penned the screenplays for Hillcoat’s The Proposition, quite possibly the greatest western of the past two decades, and the engaging but uneven 2012 bootlegging drama Lawless.

20,000 Days on Earth isn’t a documentary so much as a mystical reverie centered on the life of the creative mind, the cinematic walkabout of an artist determined to take control of his celebrity before it takes control of him. As Cave himself observed during a recent interview with Rolling Stone, “The more attention you absorb, the more monstrous you become.”

Landon McDonald is a graduate student studying public relations. His column, “Screen Break,” runs Wednesdays.