USC researchers develop brain implant to improve memory

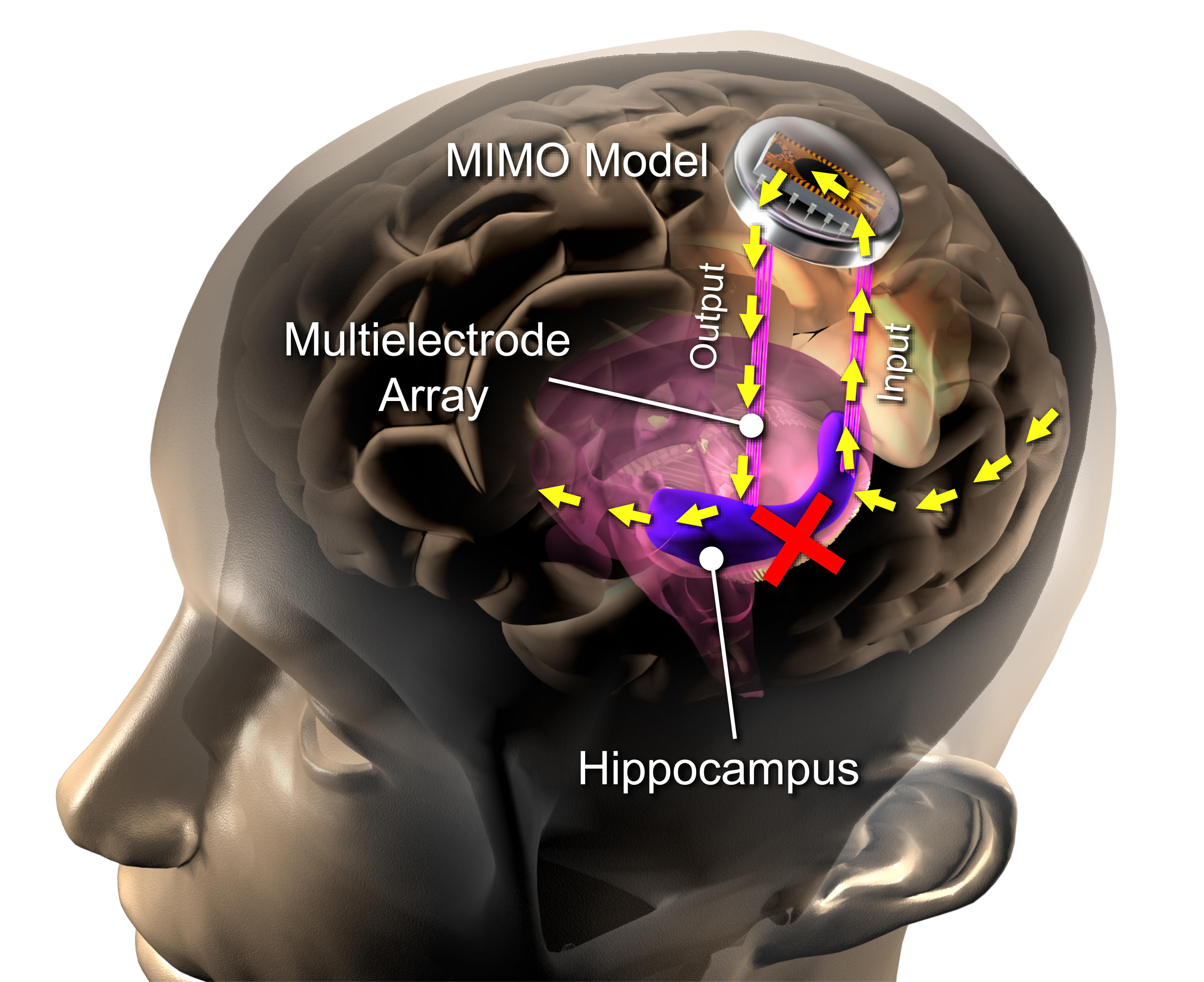

A team of university professors tested a brain implant that could improve long-term memory of humans. Diagram courtesy of Dong Song

USC researchers recently demonstrated how brain implants can be used to improve the long-term memory of humans, which has the potential to treat damaging diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

At the Society for Neuroscience conference in Washington, D.C. earlier this month, USC professors Dong Song and Theodore W. Berger and Wake Forest University professors Robert Hampson and Sam Deadwyler presented findings about the brain implant device from the past three years.

The overall goal of the project, which has been going on for over 20 years, is to construct a “memory prosthesis” device that restores the memory function of the brain through the hippocampus, a part of the brain that is critical for the formation of long-term memory. According to Song, patients with brain-impairing diseases or injuries were each found to have a malfunctioning hippocampus.

“Even though these patients can remember some old memories, they can no longer generate new long-term memory, [and] can remember things for only a short period of time,” Song said. “We are trying to fix that using an engineering approach, so we built a mathematical model to describe how the hippocampus processes information.”

Song said the device starts by recording the brain’s activity patterns. After processing this information with a computational model, the implant predicts what the correct signal should be, and through small electric shocks that stimulate the hippocampus, it mimics normal brain activity and writes in that signal back to the hippocampus.

“The hippocampus is much like a bridge back to the neocortex [which regulates conscious thought], and what we achieved now is basically proof of that principle,” Song said. “We recorded from the stimulation of a very small number of neurons, [and] we showed that the memory functions at a certain level.”

With this device, the researchers conducted hundreds of trials with 20 epileptic patients who had implanted brain electrodes. In each trial, the team had patients perform a simple memory task. First they were introduced to an image, which ranged in complexity from standard clip art to something more abstract and difficult to name. This image then vanishes, and after a variable delay, which increased with every subsequent trial, patients were then shown several images, from which they had to select the correct one.

“Based on the performance, [we got] the forgetting curve of the patients’ memory — from a certain length of delay, patients have good memory, [but with] a longer delay, [their memory] is not as good,” Song said. “From this device, we are trying to prove that we can get this curve to go upwards, and the percentage of the correct response was higher.”

According to the team’s study, the device can boost memory performance by up to 30 percent, but Song believes that this is only the starting point in the team’s research. He hopes the team will be able to develop a clinical, wired device that patients can wear or have implanted into their brains to improve and restore long-term memory for the rest of their lives.

“I personally want to solve a problem, like fix a certain disease,” Song said. “We need to make the device more general, more powerful, [and be able to] last longer, do multiple memory tasks and be truly implantable, so it’s still a long way to go.”

Interesting research being conducted.