Counterpoint: Professors’ political views cannot alienate students

By the fourth week of classes, students are more familiar with their professors, and know more about their teaching style, rigor and, in many cases, political views. While understanding their professors can help some students navigate their classes, it can also deter others.

Some believe classroom settings should remain politics-free. And yet, keeping classes this way would not only be ineffective, but would also hinder class discussions. While professors do not need to explicitly state their political views, discussions of current events and political issues will typically take place anyway. Even non-humanities professors can be eager to share their political views, perhaps in a discussion during office hours.

Talking politics with professors has several benefits: It can expose students to new viewpoints, encourage students to open their minds and even question their own views.

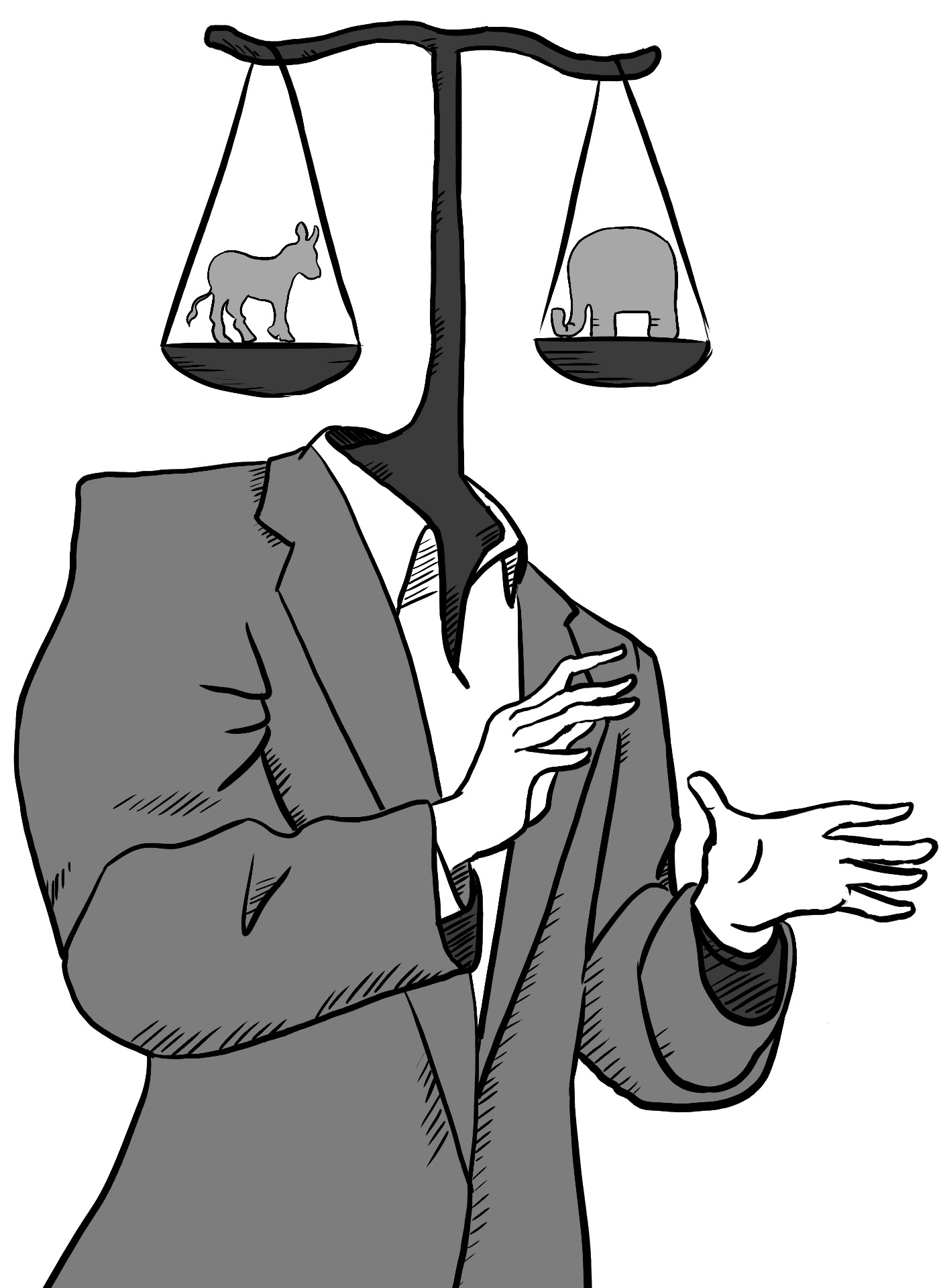

While a professor’s political affiliation is not something to fear, their political bias is. Of course, not every professor is politically biased against those who disagree with his or her points of view — to say so would be absurd. But to say that none are is equally wrong.

According to a 2016 Washington Times study, liberal professors outnumber conservative ones at 40 of the nation’s most prestigious universities by a 12:1 ratio. Of five departments the study analyzed, economics was the friendliest field to conservative students with the liberal-conservative professor ratio at 4.5:1. In contrast, liberal history professors outnumber conservatives by a 34:1 ratio.

Of course, the numbers expose the overwhelming liberal majority and lack of political diversity at elite universities. This is a problem independent of the political bias question. After all, even if the liberal to conservative ratio were 1:1, it would not eliminate skewed opinions about students of opposing viewpoints.

There is little to no data on political bias because many of its impacts cannot be recorded concretely. Since bias is subconscious, it is hard to show the observable implications with numbered data. Indeed, grades may be the exception, but political bias generates discomfort among students with different opinions, who may be reluctant to participate in discussions or unwilling to attend office hours.

Do we want to have meaningful political debates and conversations in class? Of course. But there are two prongs that must be achieved for such conversations to take place. First, professors must share their political views. Second, students must be willing to share their own views as well.

While igniting political conversations can start class discussions, not all students will chime in. Typically, only students who share the same viewpoint as the professor speak up.

But should students who fundamentally disagree with the professor be expected to voice their opinions? Idealists would say yes. Realists know this usually isn’t the case.

Students with opinions that differ from the majority’s may be deterred from sharing their point of view. And it’s hard to blame them. They have far more to lose — the respect of their peers in some cases, the judgment of their professors and maybe even their grades.

Let’s face it — all professors and students have political opinions; nobody is politically neutral. And professors should be free to share their views. However, they should not expect outward disagreement and intellectual debate to ignite automatically. Instead, professors ought to make clear that they welcome disagreement. If they truly want their classrooms to be considered civil places for debate, they must facilitate the conversation neutrally and keep their grading separate and objective.

Shauli Bar-On is a freshman majoring in political science. “Point/Counterpoint” runs Wednesdays.