Power and Privilege

Straight to Troy: Pipelines of power

USC athletes have world-class talent. But they are often recruited from just a few elite, private institutions.

By Hailey Tucker

6:00 a.m. weight training sessions. 8:30 a.m. class. 12:00 p.m. lunch. 2:30 p.m. watching film. 3:30 p.m. practice.

This schedule sounds standard for an NCAA student-athlete, but what about for a high schooler?

Elite athletic departments like USC are utilizing intense high school athletics to find top recruits around the country.

Steven Kramer | Daily Trojan

For redshirt junior baseball player Angelo Armenta, the college-like atmosphere of his high school propelled him to the Division I level.

“I think it was good because we did a lot of morning lifts, it wasn’t really like high school, it was more like college-based practices and stuff,” Armenta said. “We would lift in the morning, we would practice for a couple hours and everything was really organized and the coaches were pretty on top of their stuff.”

Along with the advanced training of athletes, the connections that high schools develop with universities can impact where athletes play at the next level. Connections are nothing new for the Trojan Family, and athletics are no different. For sophomore linebacker Oluwole Betiku, who grew up in Nigeria, the connections brought him to USC. Betiku is one of nine current football players who attended Junipero Serra High School, also known as Gardena Serra, in Gardena, Calif.

“Man, it’s like a lot of players from there go to USC and the players who go to USC make it to the NFL and they get a good education, too,” Betiku said. “You just hear good stories about the program, so being at Serra and seeing those guys come back all the time and hearing their stories just makes you want to be a Trojan also.”

High schools are putting more money into their facilities, resources toward preparing their students in the classroom and hours into training them on the field, but producing successful athletes on a large scale requires one thing — money.

USC recruits athletes globally, but has established pipeline schools within the area. The three high schools with the most athletes at USC currently are all private, extending the University’s exclusivity.

The USC Athletic Department declined to comment for this story.

Establishing a pipeline

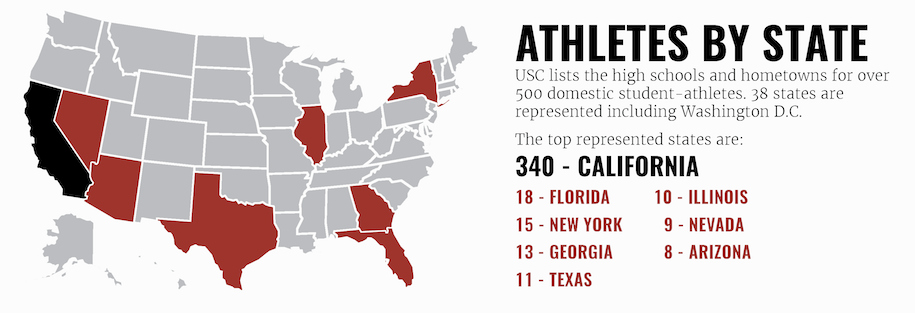

For USC, California is the big-picture pipeline. Nearly 70 percent of domestic student-athletes hail from the Golden State, compared with only 42 percent of the admitted freshman class of 2017.

Armenta and Betiku come from Loyola High School and Gardena Serra High School, respectively. Loyola and Gardena Serra are the second- and third-most represented high schools among athletes, with Loyola producing 10 and Gardena Serra nine. The only high school with more athletes at USC is Mater Dei High School, in Santa Ana, Calif., which has 19.

USC isn’t targeting these schools because they are private, but because they produce nationally acclaimed athletes. The schools have the resources to produce these athletes because of their money.

“Private schools, not that they have limitless resources, but we don’t have to worry about getting a bus for the team or other things that a lot of public schools have to scrape by with,” said Chris O’Donnell, athletic director at Loyola High School. “A lot of private schools don’t struggle for the basics. We may have to decide what to concentrate our resources on, but it’s not the basics.”

Founded in 1865 — 15 years before USC — Loyola is the oldest high school in Los Angeles. The Jesuit, all-boys school boasts on its website that 100 percent of its graduates pursue higher education. Similar to the lifelong loyalty that Trojan alumni show, at Loyola, there is a tradition of legacy.

“I was pretty much going to go there no matter what unless I didn’t get in,” Armenta said. “My dad went there too. So that was basically why I was going to go there. There’s a lot of grandparents and dads that go there.”

O’Donnell said such stories aren’t unusual, adding that alumni have called him and said they plan to move back to Los Angeles from the East Coast so that their sons can attend the school.

An advantage private schools have is that they can pull students from all over without worrying about the boundaries of a school district. Loyola serves over 200 ZIP codes, according to its website.

“Mira Costa [High School] only gets students from a small area,” O’Donnell said. “We get students from a large area of ZIP codes so we can get the best of the best. If we were a local school, we would be limited to the people who lived around us.”

Advantages on and off the field

While the top three schools are all private, they are followed by Mira Costa, in Manhattan Beach, Calif. There are currently eight student-athletes at USC from Mira Costa.

Although it is a public school, the affluent community that Mira Costa serves has allowed it to provide services and facilities reminiscent of a private academy. The school recently passed a $39 million bond that will create a new facility for gymnasium sports and training facilities, in addition to a $6 million synthetic turf field.

“When the community is putting $39 million into the gym and $6 million into the field, the argument is that we have to do our job with the athletes as well,” said Glenn Marx, the athletic director at Mira Costa. “The reason is, you are competing with the private schools in affluent areas. People who move into our community are affluent and we want them to feel that they can stay local and get a good education at our public school.”

In addition to the athletic facilities, student-athletes have more resources on the academic side to help them get to college. At Mira Costa, Marx and vice principal Stephanie Hall head up a College Recruiting Advisory Program. The program focuses on making sure that the athletes are meeting all of their core class requirements to qualify for college on top of advising them on some of the trickier aspects of the recruiting process, such as visiting campuses and managing offers.

This contributes to the success of student-athletes coming out of Mira Costa, but Marx also says it has a lot to do with the community and family life.

“Because of the affluent community, there is a desire for kids to go to college and keep up their grades and go to a school like USC,” Marx said. “It’s a combination of the affluent community — kids are more likely to take AP classes and get tutors — and the facilities, which enhance performance along with the influence of the club circuit.”

At a private school, those things are taken for granted. For Loyola, athletics isn’t the main focus, though it comes along with having wealthy and talented students from across Los Angeles.

“Having scholarship athletes is not the main course of the meal, but it is a spice that makes the meal taste that much better,” O’Donnell said. “Not that we don’t want our athletes recruited — it just isn’t the end-all-be-all. We want them to get better and get into college. If they can get into a college that they want to because of their athletics, that’s what we want. And if they get money on top of that, it’s even better.”

Loyola has 11 counselors who help guide students through the college application process.

“We put a lot of effort into our kids going to college and where they are going to college,” O’Donnell said.

The resources that private schools can put into their students don’t stop in the classroom. Armenta said he played on teams outside of school that were organized by his high school coaches.

“Our coaches had connections so they would hook us up with travel teams, club teams, so we would get extra work on the weekend,” Armenta said. “We’d face different players who were going to go to the next level on the weekends, so it was good to prepare us for college.”

Administrators said that generally those who can afford a private school can afford club teams and private coaching. It speaks to the advantage that athletes from wealthy backgrounds have in their early playing days.

“If they can afford $20,000 tuition, they can probably afford private hitting coaches, trainers and afford travel ball,” O’Donnell said.

This all contributes to the likelihood that these athletes will have the opportunity to go on to play in college. Not only is there advanced training, but there are also extra opportunities to earn a scholarship.

“We had a club team run by a different coach,” Armenta said. “We went to Arizona for the Junior Olympics. We played there to get looked at by college coaches. We’d have practices with college coaches there so they could see us. Just more exposure, basically.”

USC’s top ten athlete feeder schools are all in Southern California.

The top three are private schools.

All in the family

For many high school athletes, playing at the collegiate level is on their mind from the time they get their varsity letters. However, for Betiku, the dream of playing football for USC came from an entirely different place.

“Honestly, just looking at a program, an education and what the school had to offer besides football, I just felt like USC was the best place for me to develop as a person, as a man,” Betiku said. “Coming from Nigeria, going to a good school like this was just a dream, something that I never saw happening.”

Betiku didn’t step onto a football field until his sophomore year of high school. Under the guidance of former NFL player and guardian LaVar Arrington, however, Betiku received top-notch coaching both at home and at school. The draw to USC made sense for him and he was exposed to it early and often in his playing career. Throngs of Serra players have gone on to become Trojans, such as Deontay Burnett, Rasheem Green and John Houston Jr., whom Betiku played with in high school.

“My senior year I would always come here to hang out with them every other weekend,” Betiku said. “I already had a feel for the team and the guys who are around.”

The sentiment was the same for Armenta, who was able to connect with former teammates who went on to play at USC, such as former Trojan Corey Dempster.

“He told me what to expect and I was prepared more because of that,” Armenta said.

These connections can be invaluable for creating lasting relationships between USC and the high schools it recruits from.

Despite pulling athletes from 38 states, USC has 340 student-athletes from California. Five of the top-10 represented high schools are private. The advantages of attending a private high school are significant, but attending a public school in a wealthy neighborhood adds up to a lot of the same resources. Armenta says there is a clear advantage in going to a private school, if you use of all the extra resources that are available.

“It helps a lot being from a private school,” Armenta said. “You have more resources, but once you get here [USC], it’s just the same.”

Money and power follow Cardinal and Gold in the classroom and on the field. Athletes come from everywhere and USC finds top-notch talent regardless of what neighborhood a kid grew up in.

However, as far as patterns over time are concerned, affluency leads to success, and it starts well before anyone steps on campus.