Fisher Museum exhibit comprises Holocaust survivor testimonies

The USC Fisher Museum of Art and the USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education opened its Fall 2019 exhibit “Facing Survival,” an interactive testament to Holocaust survivors, Wednesday.

The collection, which will be held at Fisher until Dec. 7, includes 14 paintings by international artist David Kassan and the “Dimensions in Testimony” holograms, or interactive biographies, of Holocaust survivors Eva Schloss and Pinchas Gutter, which can each answer questions about their experiences inside concentration camps during World War II.

According to Executive Director of the USC Shoah Foundation Stephen Smith, several USC faculty and staff members have been working hard to make “Facing Survival” a reality. Smith said the project was conceived seven years ago when he conferred with a colleague who had a vision for the foundation’s role in a frightful near future where Holocaust survivors’ stories became lost and forgotten history.

“[At the gallery’s opening ceremony] 10 Holocaust survivors were here, we got to speak to them, then they can tell us that story personally,” Smith said. “When they are no longer able to do that, how will you continue to [get visitors] deeply engaged? The idea behind [“Dimensions in Testimony”] is they can still tell their story.”

While the USC Shoah Foundation continues to add to its video archive of over 50,000 Holocaust survivor testimonies, “Dimensions in Testimony” aims to replicate a similar emotional connection through an interactive medium. This process is meant to be intimate, forcing visitors to think, ask questions and make connections between survivors’ experiences and injustice in the world today.

Smith said that the Schloss and Gutter interactive biographies are programmed to answer comprehensive questions about their history and that their responses are nothing like what students can find in a traditional textbook. When visitors speak into the exhibit microphone to ask their questions, they should feel as if they were having a conversation with a survivor who had just sat down to tell their tale, Smith said.

“I noticed in my own research that when survivors were telling their story, [students] would ask, ‘Do you hate the Germans? What they did to you? How do you feel when you see racism in the world today?’” Smith said. “And the questions were about the consequences.”

Each interactive biography was made using 360-degree video footage. The virtual images of Schloss and Gutter will be available at Fisher on a rotating basis.

Similar interactive biographies in “Dimensions in Testimony” created by developer Conscience Display have been exhibited in the Swedish History Museum and the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles. Selma Holo, director of the Fisher Gallery and a professor of art history, said visitors need to remember stories about the Holocaust because genocide and persecution are not things of the past.

“There’s been a whole change in the way people understand history,” Holo said. “There is the distance and the danger of forgetting.”

“Facing Survival” aims to make history accessible to a generation faced with diminishing eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust.

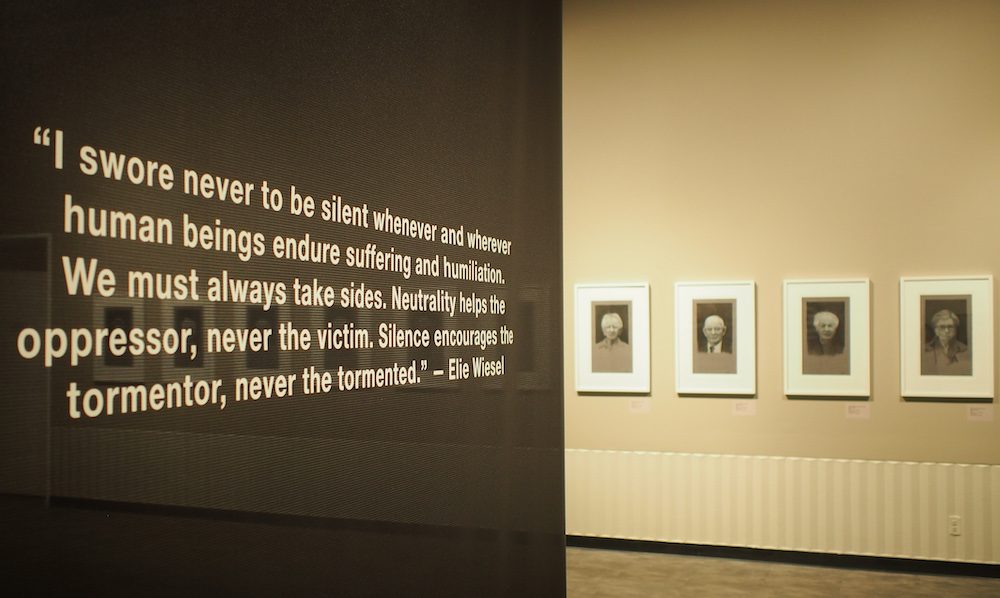

Kassan’s paintings, which fill most of the gallery space, represent another type of testimony in “Facing Survival.” Smith said that Kassan’s work affects viewers in part because it follows Shoah Foundation methodology and incorporates survivors’ stories into his work.

“He would sit with the survivors, talking, working with film and photographs — that is exactly what we do,” Smith said. “And in his case, the output is a piece of art. He gets the intensity of that story, which I think speaks through the artwork, because of his engagement with the survivors … I think he’s done justice to their legacy.”

Kassan started painting Holocaust survivor portraits when he asked a colleague if he could paint her parents; the project later grew into the series now on display at the Fisher Gallery. Kassan said that a single painting can take between two months and two years to complete.

“I just take my time,” Kazan said. “I’m not making products, I’m making paintings. They’re more about the experience as opposed to making something to sell. There’s a saying: the brushstroke lasts longer than the hand that made it, so these things are hopefully going to outlive me. And then if it takes me an extra month or a year to finish a painting, that’s worth it, because they’re going to live on way past me.”

Kassan, whose earlier work has been featured in the Smithsonian, does not think of himself as a portrait artist but rather as a painter with a wide range of interests who combines abstract and impressionist backgrounds with raw human figures as the subjects. He plans to continue painting Holocaust survivors because, as he says, listening to survivors’ testimonies makes painting them an intimate process.

In attesting to the power of these testimonies, Kassan said that Eva Schloss’ story highlights how giving testimony has helped Holocaust survivors make peace with their own pasts.

“There’s the whole spectrum of humanity, or how people deal with things,” Kassan said. “Some people lock it away. Other people were very angry, and they weren’t able to talk about it early in the 1960s and 1970s. And then when they started to talk, they lost that anger, and they actually became more compassionate human beings because they were able to discuss what happened.”

Kassan and the USC staff and faculty who worked to bring “Facing Survival” to the museum want students to share the experiences they gain at the exhibit with others, including those on campus who have never visited the Fisher Museum.

Currently, the Fisher Gallery is the only place visitors can interact with Schloss’ and Gutter’s interactive testimonies. Fisher will hold a series of remembrance and social justice events related to the Holocaust throughout the semester as part of its “Facing Survival” programming. The gallery is open to the public.

“This is not your mother’s, your father’s or your grandparents’ museum,” Holo said. “If you come here, you’re going to see how we have embraced technology, how we’ve taken ancient techniques to portraiture and then made them come alive with the [interactive biographies]. It’s very powerful.”