By the time I graduated high school in 2021, I was ready to get the hell out of the Coachella Valley. I hated the scalding 120 degree summers and the suffocating nature of knowing everyone somehow. Not to mention, being locked in my house for a year and a half during the coronavirus pandemic didn’t exactly inspire positive feelings about my hometown.

It’s been nearly three years since — something hard to conceptualize — but I’ve slowly rehabilitated aspects of my relationship with the valley as I’ve grown older. Now, the annoying two degrees of separation don’t feel as polarizing.

I won’t lie, this appreciation for the familiarity of the valley is a rather recent development for me, and it inspired me to write something for Hispanic Heritage Month. As we all know, Los Angeles saw a day of heavy, continuous rain during Hurricane Hilary and, luckily, minimal damage. However, the desert I call home didn’t fare as well — by a long shot. My sister, who works at the hospital, sent me footage of the parking lot-turned lake and pictures of the emergency room, which flooded four times.

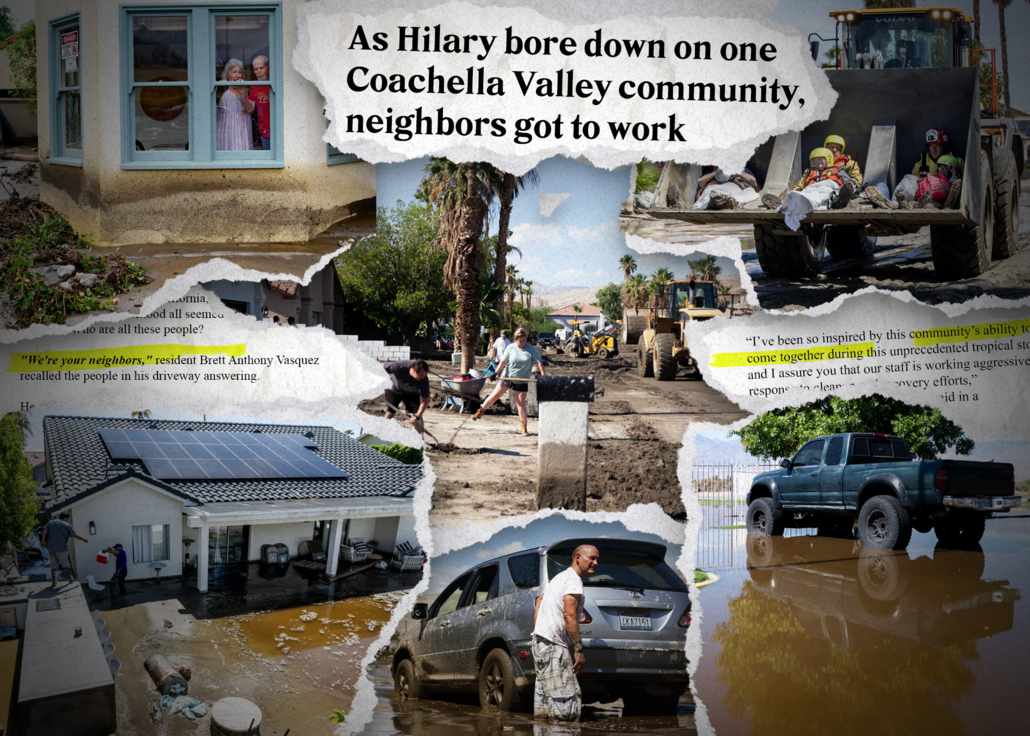

Initially, this didn’t surprise me, as our storm drain infrastructure is easily subpar to any other place that gets more than three inches of rain each year. But this was unlike any storm that the CV had seen in nearly 50 years — Hurricane Hilary inflicted upward of $126 million of damage across Riverside County, and it was painfully evident. Main roads in Cathedral City and Palm Springs, such as Date Palm Drive and Vista Chino, were unrecognizable under multiple feet of mud. Stranded vehicles littered the streets and Interstate 10.

Residential streets in Cathedral City suffered extreme losses after the water made its way into peoples’ homes. After the flood, up to four feet of mud were left inside for homeowners to shovel out themselves. However, they didn’t have to do it alone.

Nearly 90% of my high school classmates were Latine — I, along with essentially all of my hometown friends, am Mexican. In my childhood and adolescence, I was undoubtedly spoiled by the care and affection of my family, friends and friends’ relatives — and I have no other explanation other than it’s just what Latines do. They want to see you safe, happy and successful, and will do most anything to see it through.

Knowing that this is the quality of people in my town, I wasn’t surprised when I found out about the community wide effort to help those affected by the hurricane.

Ellisa Mendiola and her family’s home was one of many on her street in Cathedral City who found themselves at a loss over how to clear their home of several feet of mud. Mendiola suggested that her family reach out to the community for help over social media.

“We were just hoping for 10 people … We probably had 20, 25 people per day, so it was a great amount of people,” Mendiola said. “Just having that many people show up for us — it was amazing.”

The shoveling effort went on for nearly a week following the storm, Mendiola said, with volunteers helping out from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Upon reflecting on the experience, Mendiola stressed an appreciation for her fellow Latines: “It’s made me feel more grateful for the Latine community … and just so proud of where I came from.”

Another community member and one of the organizers of this effort, Topaz Mejia, recounted the immediate aftermath that motivated her to mobilize the community: “It was so much worse than we could have imagined … Some of the rooms [in the flooded houses] had mud past my knees.”

Mejia’s resolve was strengthened after some of the residents mentioned that, due to the circumstances of the flood and the semantics of their policies, some insurance companies were either resisting paying out or flat-out not covering the damages. With this, Mejia spent an entire day passing out flyers by hand and then began promoting the volunteer effort online. Despite the unfortunate circumstances that brought everyone together, both women said the volunteers had a heartwarming, upbeat attitude throughout the laborious week.

“We were all joking, laughing — even a couple of the guys were joking, ‘Oh, when are we gonna do the tequila, haha? And it was pretty good spirits,” Mejia said. “It was uplifting and definitely hard work.”

I found myself tearing up as I interviewed Mendiola and Mejia, feeling guilty about the immature comments I’ve made about my community without truly taking stock of the moments of support that actually mattered — moments like these.

Community isn’t just support in exchange for a photo op or a chance to clear your conscience; it’s born out of a genuine concern and love for one another — considering how USC is smack dab in the middle of a thriving Latino community in South Central, we could learn a thing or two about incorporating a strong cultural obligation to care for one another in our campus community as well.