As an oil drilling operator attempts to restart operations following a 2013 shutdown, local activists are stepping up.

Community organizers rally on 23rd Street to prevent AllenCo from reopening at a public protest on Sept. 8, 2018.

Most nights around 1 a.m., Carolina would sense the odor of gasoline in the air, drifting through the windows of her home in University Park, just north of USC. She started to feel a dryness in her throat, a tightness in her chest and her daughter developed a persistent cough.

Carolina, who asked that her real name be withheld out of privacy concerns, has lived in the neighborhood for 20 years, and she's not sure exactly when these problems began.

But five years ago, other residents and neighborhood activists traced the odors back to an oil drilling site on 23rd Street, hidden behind vine-covered walls and a manicured lawn.

"It came with the breeze," the 77-year-old said in Spanish. "I'm afraid to live here because of how it affects me."

Carolina closes her windows and uses a ventilator to protect her grandson, 4-month-old Kevin Guerro, from petroleum odors near the AllenCo drill site.

The site, operated by AllenCo Energy, shut down in 2013 after community organizers connected health problems in the neighborhood to the company's oil drilling activities. In the years that followed, the City of Los Angeles sued AllenCo, and residents put pressure on the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which owns the land the oil well sits on, to shut down the site permanently.

Despite these efforts, the oil company is trying to restart operations.

Over the past several months, the company has conducted pressure and safety tests at its 23rd Street site in an attempt to meet the city's standards for reopening.

Carolina, who asked that her real name not be used out of privacy concerns, smelled gasoline and experienced throat problems while the AllenCo site was in operation.

The idea worries community organizers like Nancy Ibrahim, the executive director and board president of local nonprofit Esperanza Community Housing.

"If this company is ever allowed to open again, they are going to have another opportunity to poison the same families," Ibrahim said. "This is an issue of grave concern."

Diana Kruzman | Daily Trojan

University Park was, quite literally, built on oil.

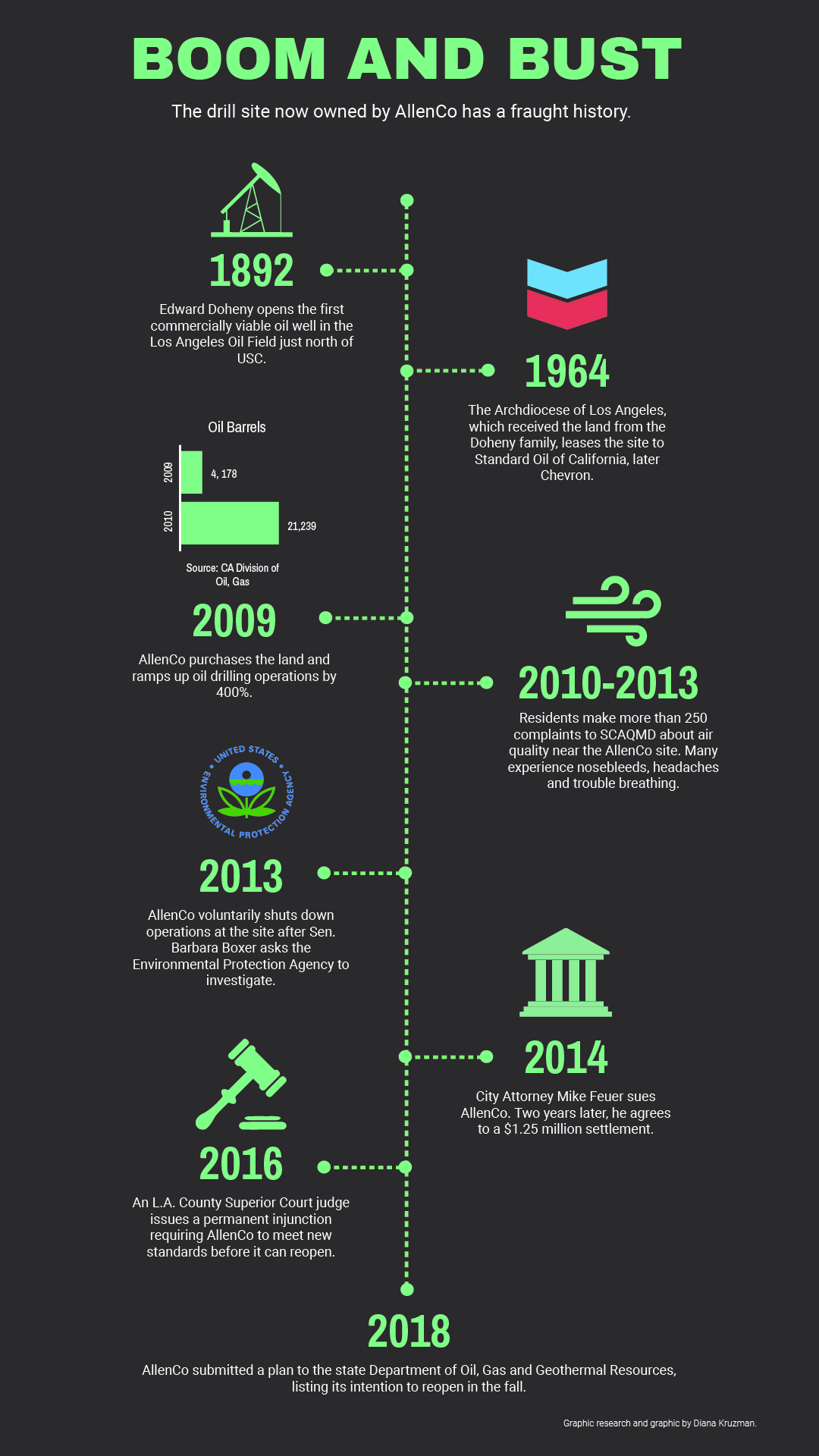

The entire neighborhood sits just south of a four-mile-long oil field stretching from Dodger Stadium to Vermont Avenue, one that Edward Doheny — who funded USC's Doheny Memorial Library — opened up to drilling in 1892. The Doheny family donated the land that now houses the AllenCo site to the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which leased the site for drilling to Standard Oil of California in 1964.

Diana Kruzman | Daily Trojan

Oil production slowed to a crawl in the 1990s, and the site remained mostly unused until AllenCo took over the lease in 2009. The company promptly ramped up drilling activities, producing five times as much oil in 2010 as the year before, according to figures from the state's Division of Oil, Gas & Geothermal Resources.

That's when Ibrahim and others in the University Park community began to notice strange odors and experience sudden health problems.

As reports of adult-onset asthma and nosebleeds trickled in, Ibrahim's organization took a public health approach to the issue, conducting community surveys to document symptoms and encouraging residents to call the South Coast Air Quality Management District to report complaints.

The "People Not Pozos" campaign used models of human heads with painted-on nosebleeds to demonstrate the effects of noxious gases in the air near the AllenCo site.

The AQMD assured them the air around the site was safe after samples found low levels of noxious gases. But as residents' symptoms persisted, Ibrahim kept calling different agencies — the Fire Department, Public Health Department, DOGGR — and said she received little information in return.

"We didn't know what we were being exposed to," Ibrahim said. "That really indicated a very deeply broken and entirely inadequate and non-protective regulatory environment, where the community's needs were either obfuscated or ignored, disrespected by the entire process."

Over three years, University Park residents made more than 250 calls to air quality officials about health problems in the vicinity of the AllenCo site, Ibrahim said. But Esperanza Community Housing's public awareness campaigns and the Los Angeles Times' reporting on the issue caught the attention of former Sen. Barbara Boxer, who asked the Environmental Protection Agency to investigate. Several EPA officials fell ill after visiting the site, and AllenCo voluntarily suspended operations later that year.

In 2014, City Attorney Mike Feuer filed a lawsuit against AllenCo, accusing the company of ignoring warnings issued by regulatory agencies, which cited the company for failing to properly deal with hazardous materials, among other violations.

Community organizers rally on 23rd Street to prevent AllenCo from reopening at a public protest on Sept. 8, 2018.

Two years later, a Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge granted a permanent injunction that required AllenCo to pay $1.25 million in civil penalties and meet new requirements before it could reopen. These included installing a health and safety monitoring system with an independent expert who could shut down operations at the site if emissions of methane, hydrogen sulfide and other gases exceeded safe levels.

AllenCo did not respond to multiple email requests for comment.

Jill Johnston, an assistant professor in the department of preventative medicine at USC, has been conducting air quality studies in the area immediately adjacent to the AllenCo site since 2016. So far, she has only been able to collect data while the wells have been closed, but she plans to repeat the study if they reopen — and, Johnston added, closed oil sites can still emit potentially noxious gases.

She said that many chemicals commonly used to operate and maintain oil wells have potentially harmful side effects. Hydrogen sulfide — a colorless, flammable gas found naturally in petroleum — causes inflammation of the mucous membranes, leading to nosebleeds and headaches. And some petroleum products, known generally as volatile organic compounds, can contribute to a higher risk of childhood leukemia, as well as cause headaches and dizziness.

These chemicals can leak into the air, Johnston said, traveling up to three miles from their source in ideal conditions.

"We don't understand enough about how these chemicals are traveling," Johnston said.

For local activists like Hugo Garcia, shutting down oil drilling operations at AllenCo is an issue of social justice. Garcia runs the "People Not Pozos" — referring to the Spanish word for oil wells — campaign for Esperanza Community Housing.

Esperanza Community Housing, a neighborhood organization, has organized public awareness campaigns — such as "People Not Pozos" — to try to shut down the AllenCo site permanently.

The area where he works near the drill site is home to a mainly low-income, immigrant community with large numbers of undocumented and monolingual Spanish-speaking residents. These populations, Garcia said, are particularly vulnerable to health issues because they may not know how to fight back.

"It's not a coincidence that you have these facilities operating in communities of color," Garcia said. "There's a lot of ground we need to make up. We think it's about time."

No tests have concretely proven that fumes from AllenCo sickened residents, but officials have found some evidence that volatile chemicals have seeped into the air surrounding the drill site.

In January 2011, 13 people fell ill at the Doheny Campus of Mount St. Mary's College, next door to the AllenCo site, after hydrochloric acid fumes escaped the oil wells, according to the city's 2014 complaint against the company. And in August of that year, air samples from a wastewater tank discharge line found hydrocarbons — which can be toxic — at 10,000 times the concentration of the surrounding air, the AQMD reported.

Hugo Garcia, an organizer for Esperanza Community Housing, has worked with residents to develop a public awareness campaign and demand that AllenCo close down its operations

For Ibrahim, however, it's not a question of whether AllenCo can reduce its emissions down to "safe" levels. She believes oil production is fundamentally incompatible with the needs of a residential community.

"We wanted the City Attorney's office to protect our community by shutting them down," Ibrahim said. "What we were talking about was not only a nuisance, but a burden of illness that in many cases has created permanent injury for folks."

Because AllenCo leases the 23rd Street site, activists have focused on pressuring the Archdiocese to sever its relationship with the oil company, particularly because of the neighborhood's strong Catholic ties.

"There is an incredulity that the Archdiocese will not be more protective of its parishioners — a sense of dismay and disappointment and betrayal," Ibrahim said.

Garcia hopes that the Archdiocese can find an alternative use for the site, such as a park or an affordable housing complex.

The AllenCo oil field sits behind a tall fence, half a mile north of the USC campus and immediately adjacent to schools and residences.

"It would be a win-win scenario — one that's in the community's best interest," Garcia said.

But the Archdiocese maintains that it doesn't legally have the right to shut down the site. According to Archdiocese attorney Ed Renwick, the lease allows oil drilling operations to continue as long as AllenCo has equipment present.

"We have no objection to see if this property can be repurposed for something else," Renwick said. "We are not tied to it as a drill site. But we have no power over it because the lease is to continue so long as AllenCo is making use of the property."

Various city officials have also tried to shut down the site. City Councilman Gil Cedillo suggested in 2017 that the city could cancel oil drilling districts that were no longer considered active. In September, he directed the city attorney to report on all legal options that could prevent AllenCo from reopening.

While Petroleum Administrator Uduak-Joe Ntuk said that AllenCo's oil drilling district could not be considered "inactive," the City Council could just repeal the drilling district altogether.

AllenCo doesn't appear to be deterred by these efforts. The company has spent $700,000 upgrading the site to meet regulations, Renwick said, and in September it submitted a written plan to DOGGR describing its plans to restart operations at the facility. The proposal detailed plans for around-the-clock supervision and an emissions monitoring system, but federal, state and city officials will have to sign off on the changes before production operations can begin, according to an email from DOGGR media relations manager Don Drysdale.

Community organizers rally on 23rd Street to prevent AllenCo from reopening at a public protest on Sept. 8, 2018

Drysdale could not provide an estimated reopening date, but said that AllenCo has been conducting pipeline and tank integrity testing under the supervision of state regulators.

For Ibrahim, the return of full operations at AllenCo would signal disaster. In alignment with environmental justice organizations, she wants to enact a 2,500-foot safety buffer between oil production facilities and residential communities in Los Angeles.

And in University Park, she hopes to assure residents that they can live without fear of sudden health problems — as they have since AllenCo suspended operations in 2013.

"For five years, our community members have been able to open up their windows and have a cross-breeze in their apartments," Ibrahim said. "The severe symptoms that occurred during the heyday of oil extraction have largely abated."