Study finds possible treatment for alcoholism

Research from the USC School of Pharmacy has found a potential new drug treatment for treating alcohol use disorder through using a common anti-parasitic medicine.

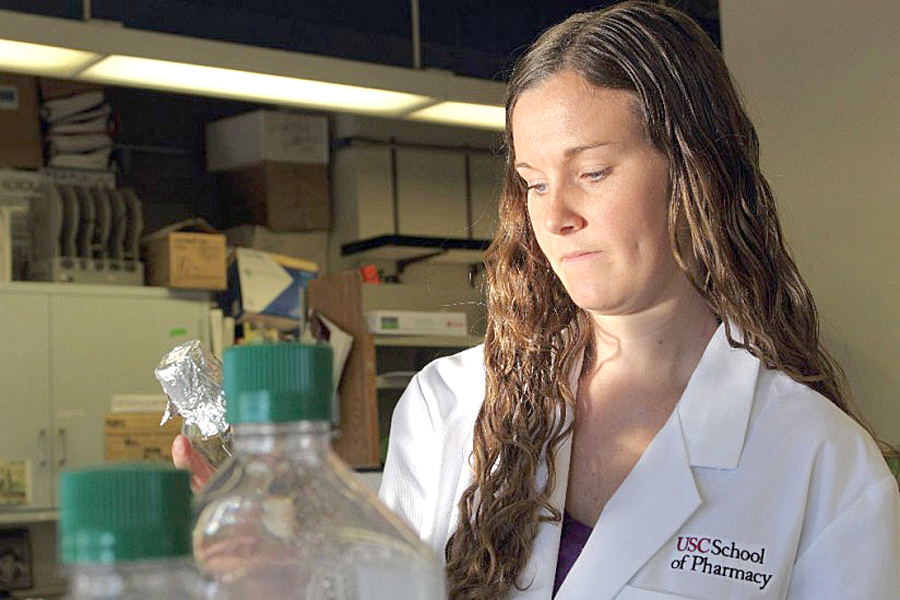

Trojan science · Ph.D Candidate Megan Yardley has been a member of the research team for five years and says human trials are “promising.” – Phillip Channing | USC News

The drug, ivermectin, has traditionally been used to treat parasitic infections in humans and animals.

The results of a five-year animal study by the school, however, reveal that it may be able to do more than just that.

Using mice, the research team discovered that giving 30 milligrams of ivermectin to the rodents reduced their alcohol intake, both in social drinking models and binge drinking models.

Megan Yardley, who will receive her Ph.D. from the School of Pharmacy this August, joined the research team when they first began animal studies five years ago. She noted that the animal data has been very promising, and the FDA has approved the team to continue the research with human subjects.

“Everything is sort of lined up to start the human studies as soon as possible,” she said.

Yardley mentioned it is still too early to tell what the potential results will be from the human trials, but the possibilities of the drug will be clearer in the months to come.

“Hopefully in three months we’ll have a much better idea on how it works — whether it decreases cravings or the pleasurable effects people feel when they consume alcohol,” she said.

One of the team’s biggest apprehensions is the potential side effects of ivermectin when used on a regular basis. Currently, the drug is only taken a few times a year, but alcohol use disorder is a much more chronic issue and would need to be treated often.

“[Ivermectin] might open some doors, but again, we still have to do a lot more toxicology studies to make sure this chronic exposure to ivermectin isn’t going to be problematic,” Yardley said. “It seems really promising, and the human studies will be able to tell us a lot.”

Some of the promising attributes were that ivermectin doesn’t cause anxiety and doesn’t have rewarding properties — two characteristics that if existed, would be problematic to treating an alcoholic population.

If this treatment proves successful in humans, it could come as a welcome relief to the reported 18 million people in the United States who suffer from alcohol use disorders.

Statistics from the World Health Organization stated that there were 3.3 million deaths from alcohol consumption in 2012 alone.