Ivory Tower questions the cost of a college education

Ivory Tower, a documentary directed and produced by Emmy-nominated filmmakers Andrew Rossi and Kate Novack, examines a question that is hauntingly relevant to college students: is the value of a university education worth the cost? The documentary, which will air on CNN on Nov. 20 at 9 p.m. and 11 p.m. exposes both the alarming statistics concerning student debt and the problematic issues surrounding the idea of a relatively cheap (or even free) education.

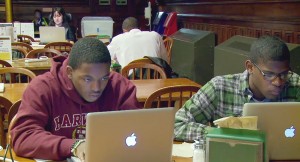

Covering all the bases · Ivory Tower presents the mind-boggling numbers associated with student debt in the country today. It also shows the stories of those who have pursued alternative paths for post-secondary experiences. The draws from both ends of the college debate. – Photo courtesy of CNN

On one hand, Ivory Tower makes a point of challenging the viewer to think outside of the box of a standard, expensive college education. The film details sobering facts, such as the facts that the national student loan debt surpasses $1 trillion and that the price of college has increased more than any other good or service, such as food or healthcare, since 1973. To complement these statistics, interviews with educational authors and professors discuss the issue of whether a student’s tuition is actually connected to his or her quality of education. The film mulls over issues of the higher education arms race for prestige, and how that race for better facilities and high-profile faculty financially impacts student tuition. In an interview, Anya Kamenetz, author of DIY U: Edupunks, Edupreneurs, and the Coming Transformation of Higher Education, states that college is a mysterious “black box” and that “we’ve never examined, closely, the ingredients of the box.” With these formidable statistics and a discussion concerning the actual destination of an individual’s tuition, Ivory Tower urgently prods the viewer to examine those ingredients.

The documentary also follows the stories of those who dare to step away from a standard post-high school experience. For example, a couple scenes focus on the Thiel Fellowship, which essentially pays its fellows $100,000 to drop out of college, live at an Education Hackerhouse in Silicon Valley and work on their own start-ups with mentors. This choice is labeled as “hacking one’s education.” The documentary takes a fairly neutral stance on this anomalistic situation, choosing to include both zealous statements by the Thiel Fellowship mentors, who state that a college education is simply an overpriced “mythical large bundle of things” and a tempering statement by the president of Georgetown University, who points out that the prodigies who are successful without a college degree, are the “exceptions to the rule” — that “the safest bet” is to invest in a college education. The film also notes that median lifetime earnings with a high school diploma are about $1,304,000, while a bachelor’s degree would produce about $2,268,000.

Ivory Tower continues this balanced style of narration by contrasting shocking financial statistics with the grim reality of the alternative to a costly college education. The documentary follows the story of Cooper Union, a college that had a mission of providing free tuition for every student up until last year. Ivory Tower follows the rousing quest of protesting students who occupied the university president’s office, insisting education, as a human right, ought to be free. Despite this, interviews with the president of Cooper Union expose the practical, unavoidable problem of making education free — or, at the very least, cheaper — when constructing a new university building costs more than a luxury hotel.

The documentary also follows the stories of start-up companies that provide free online courses, which are recorded from world-class universities such as Stanford. Though these courses drastically reduce the cost of attending a university, the results that Ivory Tower presents are acutely disappointing — one university that tried such an online program ended up with a 50.5 percent pass rate, with only a 25.4 percent pass rate at college algebra.

Ivory Tower does initially criticize America’s higher education with statistics and interviews, but it also refuses to idealize the alternatives to a costly four-year education. In fact, its exposure of the issues surrounding recent attempts to provide free education is equally biting. At one point, the film documents a speaker at Cooper Union who points out the debate about whether education should be free or not doesn’t actually exist: the real issue at hand is who is willing to pay for education. This question is the backbone of Ivory Tower’s themes: if education’s cost is to be alleviated, who else is going to pay for it, and how can quality and prestige be sustained?

At times, Ivory Tower undermines its own attempt to maintain a neutral tone: the statistics spliced into the documentary rarely come with a citation of a specific study, and in order to emphasize a certain point, the narrative focus of the documentary hones in on overwrought statistics and case studies. For example, the film quotes a study that found that its population studied “less than five hours per week” while attempting to describe the potential uselessness of a college degree. Though procrastination and unproductivity aren’t alien phenomena for the standard college student, such a statistic might sound more outlandish than widely representative. Such melodramatic moments in the documentary impair the diplomatic shifts between opposed viewpoints — the frank balance that is supposed to make Ivory Tower interesting and compelling.

Overall, however, Ivory Tower is a refreshingly fair look at the issue of college costs. On one hand, it details the absurd cost of college and dares the viewer to closely inspect the expensive product he or she is purchasing. It notes the alternatives beyond society’s pre-packaged answer of a four-year education. Ivory Tower, however, simultaneously refuses to be shy about the flaws embedded in such alternatives, and the painful necessity of a college diploma for the majority of future members of the work force. Just as the interviewed authors and professors repeatedly emphasizes that a college environment should be democratic, the film provides the viewer with several perspectives on the cost of college and leaves its conclusion undefined.