The Six Billion Dollar Man: How Nikias is engineering the future of USC

President C. L. Max Nikias doesn’t care much for fiction.

It’s not that he doesn’t like reading or he finds the tales too fanciful; he is well known as a voracious reader, and fantastical tales from the Greco-Roman era form the benchmark of his cultural references.

Non-fiction, however, is where he argues the real lessons of leadership are learned. In his free time you can find him devouring an eclectic list of past leaders, a bit of Machiavelli here and Lyndon B. Johnson there. A recent foray into Alexander Hamilton had him channeling the past Founding Father into his daily life, though he hopes, of course, they share different fates.

But upon first meeting “Max,” any preconceived notion of stiff academic or armchair philosopher quickly disintegrates. It is not Nikias the sage but rather Nikias the entertainer, and for that moment, one may wonder if they haven’t already met him before.

His eyes light up, a smile slips from cheek to cheek and a quick hand shake delivers more of a “how have you been?” than a “nice to meet you.” One might think it was rehearsed if it didn’t appear quite so genuine.

“He has a deep sense of human connection and warmth,” said Willow Bay, director of the Annenberg School of Journalism. “He is truly unusual in that way — in his ability to connect.”

It is a connection and commitment that has bled through all walks of campus life, and in the six years that Nikias has served as the University’s president, USC has only accelerated its meteoric rise from a second-choice commuter school to an internationally recognized research university of the 21st century.

The president, in many respects, has had the luxury of leaping off the shoulders of university giants before him. His predecessor, Steven Sample, has often been credited with engineering the University’s dramatic academic transformation during the late 1990s and the early 2000s, leading its rise during his 19-year tenure from 51st to 26th in the U.S. News and World Report rankings of national research universities.

Nikias’ own jump, however, has been anything but ordinary. The hallmarks of his inaugural vision — a $6 billion fundraising campaign and the construction of the 15-acre retail and residential USC Village — were deemed equal parts ambitious and foolish by respective circles of higher education when first announced. They are now both mere months from completion, with the campaign sitting nicely at $5.7 billion and the Village set to open next fall.

As he continues to push the boundaries of what this University can do, interviews with nearly a dozen top-level administrators appraise Nikias as taking both himself and USC on an Icarus-like rise without any of the fall. The question now is how the Trojan flag bearer hopes to maintain the upward momentum that has defined him since he first arrived to the University 25 years ago.

—————

In some ways, the presidency still surprises him.

“It was never in my wildest dreams that I was going to be a president of a university,” Nikias said, sitting at a table of dark wood in the President’s Dining Room while portraits of past university leaders stare down on him. “In fact, it wasn’t even in my wildest dreams when I came to USC as a professor. I had no aspiration for any university leadership position.”

When looking at his career trajectory, his assertion can be hard to believe.

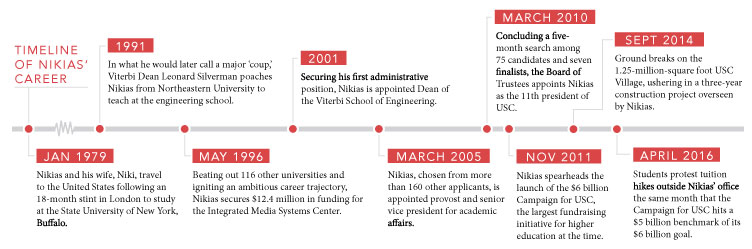

First arriving to USC in 1991, he served as a professor of electrical engineering for the Viterbi School of Engineering. Soon after the turn of the millennia, Nikias was dean of that very school. Four years later, he was elevated to provost and chief academic officer, second in command to the president. Within another five years, the administrative ascent was all but complete — he would assume the presidency of the University in 2010.

With a resume that would be the envy of every national college administrator, Nikias exudes the mythical sanctity of the American Dream. Born on the island nation of Cyprus, where he served in the Cyprus National Guard and then attended the National Technical University of Athens in Greece, he made the leap to the states in 1979 in the oft-repeated search of greater opportunity.

“I came to America with my wife to pursue a better life through better education,” Nikias said, his Cypriot-accent still strong and words ringing with all the air of a Horatio Alger novel.

It wouldn’t take long before his New England beginnings would shuffle out West. While teaching at Northeastern University in the early 1990s, the then dean of Viterbi Leonard Silverman poached him to teach at the engineering school (Nikias would later succeed him as dean in 2001). Like his presidential rise, his mark on USC would come swiftly.

By the mid-1990s he was appointed Viterbi’s associate dean of research, and in that capacity Nikias led an ambitious effort to secure what was known as the Integrated Media Systems Center, the country’s first national engineering research center for multimedia. At the time, the Internet was newly commercialized, and the decade ushered in the information technology revolution. It was a fresh frontier, and the competition for multimedia research of this nature spanned across 117 different universities looking to win the favor of the National Science Foundation. Among those competing were the likes of the University of California, Berkeley and Columbia University.

An initial attempt was rejected. He modified the original ideas and courted greater support from West Coast companies, the kind of academic salesmanship that would predict his future fundraising acumen, and it ultimately worked. In 1996, USC won the $12.4 million funding — boosted by $34 million in corporate contributions and government sources contingent on the win — in a victory that forever altered the future of not only Viterbi, but also Nikias’ stature within the University.

“Max came to a very special prominence around USC when he got that grant,” said Geoffrey Cowan, a now University Professor who served as the dean of the Annenberg School from 1996 to 2007. “A lot of who Max became at the University was the trajectory that began with that.”

It would prove to be both Nikias’ training ground and the turning point of his career; he attributes his time heading the center to be where he learned how to both conceptualize a vision and implement the strategy to see it through.

To many he worked with at USC at the time, his future rise through the University would no longer be a question of if, but when. Yannis Yortsos, the now dean of the Viterbi School, witnessed Nikias in 2001 — when Nikias was dean and Yortsos was an associate dean — already displaying the telltale sign of a talented university administrator; he was a bona fide visionary.

“He had the talent to not only stay with a vision, but engage and attract other people to the vision,” Yortsos said. “The moment you are able to do that, it creates critical mass that then accelerates the progress of that vision, and pretty much every part of his tenure here at USC you see that again and again and again.”

—————

Willy Marsh, the USC director of capital construction, sits in a drab conference room in the construction office for the USC Village. Sketches of the project’s different iterations decorate the front wall, and the building’s lack of frills are buoyed by Marsh’s childlike excitement for the University’s largest expansion project to date.

One would be hard pressed to find someone more invested than Marsh in the detailed intricacies of the Village, the future home of 2,700 undergraduates next fall. That is, of course, until Marsh mentions Nikias.

“I just never thought he would be as intimately involved with something like the tree selection,” Marsh said, eyes and mouth agape in surprise.

Down the hall in Marsh’s office, next to pictures of his wife and children, sits a portrait of the president standing triumphantly over the rubble of the old University Village shopping center. If asked, Marsh could go on and on about the president’s unusual devotion to the project, from the specific selection of stain glass windows to the entire exterior facades.

“Did he mention how I was a micromanager?” Nikias joked later when asked about Marsh.

The joke is often made that the Village is Nikias’ “baby,” and it is not far from the truth: Original plans for the old University Village shopping center called for it to be leased to a private developer for 50 years, complete with a shopping mall and apartments. When Nikias became president, he scrapped it.

“I changed all the plans,” Nikias said, with a quip that Stanford went the private developer route in a similar tract of land they had. “I made the case to our Board of Trustees. I did my homework for six months. I didn’t know if they were going to approve it. But I wanted them to know that we needed to build the Village on our terms.”

In many respects, much of the Village — with its neo-Gothic architecture, neatly manicured greenery and organized residential colleges — is the physical embodiment of Nikias’ vision to transform the University into a future epicenter of elite higher education. Though it’s Gothic Revival aesthetic screams old academia, he stiffens when others say USC is trying to become a Stanford of Southern California or Ivy of the West; for him, it is not about aspirational facsimile, but future academic benchmark: to become the USC of USC.

“It is very simple, and it hasn’t changed,” Nikias said, his voice slowing down in an effort to emphasize nearly each syllable. “What I want is for this University to enter the pantheon of the academically elite and most influential of the world — that is the vision.”

Daily Trojan File Photo

To new heights · Nikias signs the commemorative beam at the halfway mark for the USC Village in January during the spire ceremony.

It is an ambitious feat, no doubt. While the University has steadily been climbing in academic rankings, its global influence still falls short of the Ivy League and other more established universities. But when prodded to compare USC to the likes of Northwestern University or Harvard, he smirks as if he’s the only one of them who can see into the future, one where USC is the academic hub for a Pacific Rim-dominated world increasingly tilting away from the Atlantic.

That is not to say he lacks some comparison in mind. As a man of history, it comes as little surprise when Nikias delves into the annals of the past for inspiration. His fascination with Troy is well known, and he has continually painted the University as the spiritual successor to the fabled civilization. But while much of his references are usually seeped in Greco-Roman origin, his hope for USC is much closer to the modern era.

In the fashion that Oxford University educated both the citizens of the United Kingdom and the members of the global commonwealth just over a century ago, he imagines USC will mirror that same role for not only those of the United States, but the entire Pacific Rim.

“These students will become the ambassadors — the influential ambassadors that are going out there to change the world,” Nikias said of future graduates. “The smaller private competitors don’t have the numbers on their side. We could become as a university the intellectual and cultural engine of the age of the Pacific.”

Nikias’ heavy emphasis on USC’s choice location in the 21st century carries much of the vision of Sample, his predecessor, who saw Los Angeles as the de facto capital of the Pacific Rim and USC playing a central and global role in that. As fanciful as Nikias’ aspirations may sound, it’s a vision that many of his closest administrators have bought into, stating they continually channel his trailblazing energy into their own departments.

“If I get tired, I know I can’t possibly be tired, because I’m never going to work as hard as he works,” said Thomas Sayles, vice president for university relations. “It encourages all of us to really put our best foot forward.”

Asking his top lieutenants if their leader will ever be satisfied returns either a curious look or quick chuckle. In their mind, the word has simply never been in his vocabulary.

“The minute we cross things off, he puts a couple more on. It’s always the future that’s driving him,” said Provost Michael Quick. “In terms of him saying, ‘I’ve accomplished things and now I can step away,’ I don’t think that’s how he thinks at all.”

—————

“Nikias, step off it, put students over profit!” demonstrators chanted in the shadow of the Bovard Administration Building last April, hoping to get the attention of the president’s office inside.

The small group of students was protesting recent tuition hikes which drove up the cost of attendance to over $50,000 — not including the roughly $14,000 in room and board — for the first time in the University’s history. It’s a price tag that can stand in stark contrast to the president’s defining philosophy that education is the greatest equalizer of society.

When asked on the issue of college affordability, Nikias will methodically recite five leading causes of tuition’s rising cost without hesitation; it is clear that the topic is one he discusses often. At any university, no amount of vision will amount to much without the continual buy-in of the student body. Accordingly, Nikias, whose own total compensation bottoms out the top 10 highest in the nation for private college presidents at $1.42 million, often must justify to both future and current members of the Trojan Family that the benefit of a USC education is well worth the cost.

He traces the escalating price of attendance at both USC and universities nationwide to a few core reasons: the higher demand for information technology and digital media infrastructure; the expansion of financial aid (“If I were to remove financial aid completely, the cost of tuition would drop by 33 percent,” he said); the recruitment of top faculty; the maintenance of a small 9:1 teacher to student ratio at USC; and the widespread demand for first-class services.

“This may surprise you, because it was a surprise to me when I became president,” Nikias said, arms crossed and leaning heavily back in his chair. “But the students, their parents, the faculty, they expect — they demand — the very best infrastructure. Look at the University today — it’s a city within a city. You have to make sure the experience of the student is first class, and that’s expensive.”

Student qualms regarding university tuition is but one example of an undergraduate populace that often craves greater attention from their academic head of state. But at an institution where student constituents number in the tens of thousands, individual attention is more a privilege than the norm. This lack of connection often worries him.

“I wish they knew that I do care a lot about them,” Nikias said. “I always try very hard to make sure we have the right environment for them to provide the very best education possible. If you ask me what preoccupies me most, it’s this.”

Daily Trojan File Photo Halfway point · Attendees listen to Nikias’ speak about the success of the USC Village in January.

When he discusses Nikias’ relation to students, Vice President of Student Affairs Ainsley Carry, arguably the administrator who serves most readily as the liaison between the president and the students, sees a man sometimes misunderstood as too distant or unapproachable. While he commends the student body’s resolve to have their voices heard by the very top of campus authority, he stresses the reality: This isn’t a small liberal arts college, but rather a private university with the population of a large state school.

“Everyone wants to knock at the door of head of the University, no matter what your issue is — many of our kids have come from a private school setting where the headmaster is like that,” Carry said. “But this is a multibillion dollar enterprise, it’s large and a lot of people want the president’s attention.”

To combat a fate of being holed up in a proverbial Ivory Tower, Nikias has select ways to maintain his relationship with students. Just last week, the president hosted a Thanksgiving dinner at his presidential mansion in San Marino for nearly 400 students who could not make it home. Also, this weekend he will host a holiday get-together at the same residence for residential advisors and various student leaders.

And more regularly, over the course of his tenure, he has held afternoon teas with a diverse group of roughly 20 students one to two times a month chosen by his staff in order to tap into the pulse of campus opinion. In the unstructured meetings, students are asked to share one thing they like about the University and one area where they think it can improve.

“I’ve never worked anywhere where a president had these open unstructured conversation with students,” Carry said, who has previously been at five different universities.

At one tea in particular, a member of the USC Trojan Marching Band brought up concerns about the size of space allocated for his group. The student noted that the band is often showcased as the face of the University, but their space is hardly enough to accommodate even their instruments and uniforms. The observation led the president to tour the space — in the basement of Stonier Hall — where he agreed that yes, the area was much too small for the Spirit of Troy.

“I was shocked,” Nikias said, recalling the tour. “So I’ve got news for you, by this summer, they’re going to move into a much bigger space. I already approved it.”

—————

He rarely chooses to harp on the past, but if asked, Nikias will tell you with little hesitation about the darkest day of his presidency — the day when two Chinese students were shot and killed just a mile northwest of campus in 2012. It is a rare moment when the president’s tone weakens and his usual boastful timbre no longer radiates throughout the room.

“It was the lowest moment in my six years,” Nikias said, going on to also reference the death of another Chinese student, Xinran Ji, in 2014. “The way I feel about the students is no different from my children, and they were members of my Trojan Family. It was a shocking event for me.”

For a man characterized by boundless energy and an almost brazen vibrato, humility is a rare treat. But when it comes, it reveals a restraint and empathy that ultimately may be the key in keeping him from getting a bit too close to the sun.

“There’s no pretense about him,” said Al Checcio, senior vice president for university advancement. “He’s just Max.”

only facing the truth makes truth better. USC was not a very competitive school to get into and not a lot of students consider USC their priority school until Sample boosted the school’s reputation. Nikias is just inheriting a well transformed USC and putting more stuff onto it. Like more decoration and more attraction to applicants. It might be a good move to decrease the acceptance rate and increase student quality. On the other hand, USC is neglecting the rigor of the grad division. Grad division is growing exponentially. It seems the school’s population is not well balanced. It might be that the school is still at its rapid development stage. But I hope that the quality of grad division can be more consistent.

USC was NEVER a second choice commuter school. It has always been a very special place. Fight On! (My father-class of 1950, me-class of 1979, my child-class of 2015.)

This is the most well-written piece I have ever read in the DT. Well done.