From the Editors

The “University of Spoiled Children” is just one of many unfortunate monikers for USC. It’s easy for outsiders to poke fun at our school culture and the associated stereotypes, which have changed slowly as USC evolves both socially and economically.

As USC’s student body continues to diversify through initiatives designed to increase accessibility for low-income and first-generation college students, the administration has prioritized the pursuit of several ambitious projects — many of which have a high price tag. Included among these are the university’s expansion into the surrounding community through the $650-million construction of The Village as well as President C. L. Max Nikias’ $6 billion Campaign for USC.

Though the conversation about money at USC often centers on the cost of tuition, perceived wealth of the student body and the physical growth of our campus, especially compared to the greater community in which USC is located, finances play an integral and often unseen role in many other aspects of the university.

Though student loan debt and budget cuts for universities remain significant national issues, questions of money and finance are multifaceted on all college campuses. Students have recently questioned different aspects of their universities, ranging from how their schools invest endowments to tuition hikes across many of the nation’s public and private schools. At USC, students have played an active role in economic issues, such as advocating for hospitality workers, and even more recently, faculty have been a topic in USC’s financial climate, as some have mobilized efforts to start a union for adjunct professors.

In this special issue of the Daily Trojan, we hope to explore the lesser known stories of money at USC through various dimensions, from the personal to the university level. Though this is not a comprehensive analysis of the university’s financial information, we intend to provide a greater understanding of how the university operates and how students perceive money and finances on campus.

The Daily Trojan Staff

April 15, 2015

Adjunct faculty seek to unionize

By Kate Guarino

April 15, 2015

A few clicks was all it took for professor Rachel Roske to realize her health benefits would disappear the following semester. When Roske looked at the schedule of classes last spring, she was shocked to find that her name was listed next to only one course. Teaching just one class — rather than the two classes she’d taught for the prior two years — meant Roske would lose the health benefits the university provided her and her husband.

“I had to suddenly come up with an extra $450 a month to pay for affordable healthcare coverage,” said Roske, an adjunct professor of drawing and painting at the Roski School of Art and Design.

Roske is just one of a number of non-tenure-track faculty pushing for unionization at USC.

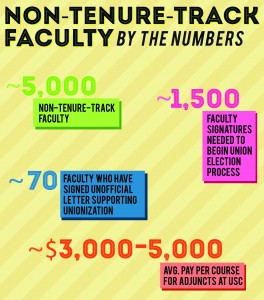

Recently, more than 70 USC faculty members signed an unofficial letter voicing their support for a unionization effort on campus. The document states that many East Coast universities including American University, Tufts University and George Washington University have formed successful unions that represent part-time and non-tenure-track faculty. These unions argue for pay increases, improved job security, fair and transparent evaluations and access to benefits on their behalf.

The movement is also gaining ground within the state of California. In January, the Service Employees International Union chapters in the Los Angeles area and in Northern California won faculty elections to represent part-time professors at several California universities. SEIU is now vying to represent faculty at USC.

A Long Way to Go

In order for SEIU to become the bargaining agent for contract negotiations at USC, the National Labor Relations Board requires a petition to be filed showing support from at least 30 percent of employees.

According to Vice Provost Martin Levine, there are approximately 5,000 non-tenure-track faculty at USC, including both part-time and full-time faculty. This means in order to meet NLRB requirements to begin the election process, roughly 1,500 non-tenure track employees would have to sign an official showing of interest.

The local 721 chapter of SEIU would not divulge how many faculty members have signed the showing of interest so far, but officials did say that the decision to call elections will be made by faculty leaders when they feel they have garnered enough support.

If a petition is filed, the NLRB will survey employment conditions at USC and determine who is able to participate in a vote to elect the union.

Some faculty have also launched a website with information about the movement. Last month, faculty and local union leaders attended a public forum in Exposition Park meant to garner interest in faculty unionization.

Among those who spoke at the event was Noura Wedell, an adjunct professor at Roski. Though she has a PhD from Columbia University, Wedell, who is in her 40s, said she lives with three roommates and moves in with her mother over the summer to help cut living expenses.

“I struggle to pay my bills,” Wedell said. “I don’t go out. I don’t buy clothes [and] worse, I’m really not as available to students because I have to do other work and I cannot buy the books and go to the conferences and do the research and travel that I need.”

Wedell said she is considering going back to school and potentially changing careers. She sees unionizing as the only way she can stay in her current position.

The Issues at Hand

The SEIU’s national faculty forward campaign is advocating $15,000 per course for adjuncts. The average salary for adjunct professors at USC is $3,000 to $5,000.

Though it has been common for part-time faculty to teach at more than one institution in the past, for many that is no longer an option.

Many adjunct faculty at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, the School of Cinematic Arts and the School of Dramatic Arts were required to sign “adjunct acknowledgment forms” (PDF) at the beginning of the spring 2015 semester.

The form stated that the university has a policy against part-time faculty teaching simultaneously at USC and other institutions because “instruction or course creation for other outside enterprises may be inconsistent with a faculty member’s responsibilities to USC.”

If faculty members wish to teach at more than one institution, they must seek approval from the dean of their particular school and “take responsible steps to ensure the proposed activity will not create conflict or the appearance of conflict with any USC program.”

Though the adjunct acknowledgement form’s legality has been called into question by some faculty members, its language does not completely prohibit other employment. It states that one must obtain permission to work elsewhere.

“It probably passes legal muster, [but] I do see that the agreement would be a great organizing issue,” wrote Bruce Harland, an attorney who has dealt with cases involving labor arbitrations and collective bargaining negotiations in an email.

Levine said that the university has long had a policy of not allowing adjuncts to teach at multiple universities but is hoping to clarify the policy in the coming year.

One adjunct, who wished to remain anonymous because of fear of repercussions, has two masters degrees, and says she is paid $4,000 per class in the fall and the spring. In addition, she was given a total of $4,000 to teach five classes online over the summer. She is the sole provider for her child and has worked at six other jobs over the course of her time at USC. She is leaving the university to take an undisclosed job that she says will pay six times as much.

The acknowledgment form also stipulates that part-time faculty are required to have a full-time job elsewhere, but for some professors in professional schools such as Cinematic Arts or Roski, working as an artist or screenwriter does not guarantee a steady source of income.

One cinematic arts professor, who wished to remain anonymous because of fear of repercussions, said she has taught at USC for more than 20 years and receives $4,900 per semester.

Non-tenure-track faculty said they are often left in the dark about program restructuring and changes to the schedule of classes.

“This is a common thing here that people just shake their heads and shrug their shoulders and wonder what’s going on and that to me is not very acceptable,” said Jamal Ali, a full-time non-tenure-track professor in the Middle East studies program.

Roske said when she and her colleagues inquired about why their course load had been changed, they were given a series of vague and contradictory answers. One of her colleagues, Roske said, took a semester off from teaching at USC to develop her artistic career but was never invited back again by the university. Roske added that another professor, who had attended USC as a student, was told the department was trying to hire fewer USC graduates, but the class her colleague lost was given to another professor who graduated from USC.

Roske and Wedell agree that the uncertainty of a semester-to-semester contract can make it difficult to mentor students and provide a promise of long-term support. Roske said she loves her students and gave up other teaching jobs to come to USC.

Still, Ali said many of his colleagues feel disheartened by the administration’s lack of transparency and support of the union.

“People are afraid that if they go public with their union support they’ll lose their job,” Ali said. “[But] the actual feeling that there needs to be change is pretty widespread.”

University Response

USC administrators became aware of SEIU’s effort on campus early in the spring semester, and the university’s response has been surprising to many faculty members.

“I hold USC to a pretty high standard and I expected them to be neutral on the movement to unionize, but unfortunately that has not been the case,” Roske said.

In a letter to faculty in February, Michael Quick, who was recently named provost and senior vice president for academic affairs, discouraged faculty unionization.

“The issue is whether a union is good for faculty at a particular university — our University of Southern California. My opinion is that it is not … We at USC have a strong system of faculty governance, which emphatically includes non-tenure-track faculty.”

The university launched a website aimed at providing information for non-tenure-track faculty about options for participation in the Academic Senate and noting some of the practices of SEIU. The website includes frequently asked questions with answers provided by Quick. In one answer, he said:

“USC’s peers nationwide are the 62 major research institutions that are members of the Association of American Universities (AAU). At only two of the 62 have adjuncts voted for the SEIU (Washington University in St. Louis and Boston University.) The SEIU does not represent faculty at any other AAU institution.”

Change from Within

The university has made strides to include non-tenure-track faculty in governance. Next year, for the first time in university history, the president of the Academic Senate — the body tasked with representing faculty interest on campus — will be a non-tenure-track faculty member.

Ginger Clark, president-elect of the Academic Senate, said the Senate works closely with Levine and Quick, and one of her goals as president is to increase part-time representation. She said as a non-tenure-track professor she hopes to provide insight to the governing body.

“I come in with knowledge that someone who comes from the tenure-track may not have about what it’s like to be non-tenure track faculty on campus,” Clark said. “I feel a great responsibility to make sure that they are represented along with our tenure-track colleagues, and I think it’s important that their issues be addressed.”

Currently, part-time faculty cannot vote in the Academic Senate. Voting in the Senate occurs by school. The 16-member Committee on Non-Tenure-Track Faculty Affairs is predominantly made up of full-time non-tenure-track faculty, but also includes some part-time faculty and tenure-track faculty. It is not a voting body.

Professor Eric Trules, who worked as an adjunct in the School of Dramatic Arts for 17 years and now works as a non-tenure-track faculty member, said he previously served on the CNTTFA, and during that time he often felt bullied by the faculty senate.

“The general opinion is that adjuncts are third-class citizens and [non-tenure track] are second-class citizens based on a dysfunctional and not very practical tenure track system that’s dying out,” Trules said.

Clark, however, disagrees. She said at times there was a “difficult melding” between tenure and non-tenure-track faculty, but the relationship has softened.

In a statement to the Daily Trojan, Quick said there will be a concerted effort to continue to better the experience of part-time faculty.

“USC has made tremendous strides over the past few years in improving the conditions of part-time and [non-tenure track] faculty, and we will continue to do more,” Quick wrote. “An SEIU faculty union would set up an adversarial model that I don’t think is good for our faculty.”

Clark said if faculty were to ultimately unionize, the school would adjust.

“Some of the challenges have to do with ensuring that everyone has the same access to resources; everyone has the same benefits and everyone is treated with the same level of respect,” Clark said. “I think we’re making good progress there but we definitely still have some work to do. If there is a union formed on campus among faculty members then we will adjust to it.”

Clarification: An earlier version of this article said that one of Rachel Roske’s colleagues was told by USC that her art career was putting a strain on her ability to teach and was let go. To clarify, USC didn’t tell explicitly tell her anything; she was never invited back to teach at USC after taking a semester off.

Workers Reflect on Wage Dispute

By Sarah Dhanaphatana

April 15, 2015

Whether it be a quick run to grab food at Seeds, or a sit-down lunch at Moreton Fig, students interact with workers from USC Hospitality and Auxiliary Services every day.

For the past nine months, UNITE HERE Local 11 labor union and the university have negotiated back and forth to reach a new five-year agreement that included a 75 cent raise from $11.00. The contract proposed an outline with reforms to create higher wages for university workers as well as increased hours, health care benefits and paid sick days.

On March 13, the university and UNITE HERE Local 11 reached an agreement advancing specific changes that met the needs of the university workers. The contract between university workers and administrators establishes higher wages and workers benefits, along with an incremental pay increase over the five-year period.

The fight began shortly after the workers’ previous five-year contract ended in June 2014. Prior to the contract, workers and university officials became involved in what seemed like a strained work dynamic consisting of irritated workers and university officials who said they were doing everything they could to take care of their employees.

“The union workers are part of USC Hospitality employees, they are part of the Trojan family, they are USC Trojan family members,” said Kris Klinger, director of USC Hospitality. “It’s business as usual. Even during the time that there was no contract in place, we still treated our employees as we always have, with respect and dignity and nothing changed during that process — before, during, and after, we’ll still do everything we can to make sure that we take care of our employees, that they earn a fair wage and are appreciated for what they do.”

According to the 2015 Auxiliaries and Athletics individual revenue center summary, direct revenues for undesignated hospitality funds have totaled $46,508.

Jim Kalen, assistant vice president of Budget and Finance at USC, discussed the way in which revenue and expenses correlate with Hospitality and Auxiliary Services.

“Hospitality services is a part of our Auxiliary Services and they’re a revenue center which balances their revenue from their expenses,” Kalen said. “So when there’s pressures from, let’s say, wage increases they would package their revenues to meet their expenses. So they’re wholly contained within their own unit. In other words, tuition dollars do not go to Auxiliary Services, other than what you pay for something at one of the restaurants.”

For nearly 30 years, workers at USC have been unionizing to create feasible change on campus. To many bystanders, the relationship between university officials and workers has been a mystery.

A Daily Struggle

Mario Perez, 47, has been a Housing worker at the university for more than eight years. He is an active member of the labor union and, prior to the amended contract, felt that he was bound to the terms included in the prior agreement.

Flash forward, and Perez now says that he is excited about what the future will bring with the new amendments to the former agreement. With the new terms of the agreement comes the ability for him to live with a lessened burden of burgeoning living costs in Los Angeles.

Perez said USC has had an impact on his desire to voice his passion toward fair and equal treatment.

“I am involved because we have a contract that sometimes the management does not respect,” Perez said. “They act like … we have to obey them … they use their power to pressure us and stress us… not all of them, but some of them.”

After working at the university for years, he has brought to light issues he felt were important in effecting change. Perez said some of the individuals working in management did not contribute as much time or effort they should have in helping the workers excel.

“We work and do things for students, and hope that students have a good experience when they are at USC, but this kind of management doesn’t care about what we think or what we do, they just want us to work,” Perez said. “We are part of the Trojan family, we do our job for future lawyers, future doctors, future athletes in football — we work with them every single day, so these are our concerns and if we have a contract we want management to respect it.”

Carmen Arredondo, 50, has had a similar experience. Arredondo has worked at the University Club on the University Park Campus for nine years. She enjoys her job and since she began working in the summer of 2006, she has witnessed the progression of increasing workers benefits.

“I am so lucky to be working for the University Club because I have the ability to serve the professors and deans of the university,” Arredondo said.

She became an active participant within UNITE HERE Local 11 at the beginning of her employment at USC, when she heard that her co-workers from separate Hospitality and Auxiliary Services divisions expressed similar concerns in terms of contract violation.

“I realized that someone had to do it [get involved],” Arredondo said. “We took the initiative to take the action to get more involved in the issues that we have as employees at the university. Although we have a contract, we have to go with the rules of the university and the rules we have in the contract.”

Arredondo commutes to and from work each day. For the past nine years, she has driven from Monterey Park to Los Angeles. Recently, the high costs of paying the fee for a parking pass has driven her to arrive to work extra early to find parking spaces on the street to save money. She also said many of her co-workers have found alternative methods to parking passes by using the Metro or bus.

Klinger said the division works to fully accommodate workers as best as they can, but sometimes it is difficult to make everyone happy. He did, however, say that the contract was a positive starting point because the terms of the agreement allowed representation for both the workers and the university.

“We really appreciate our employees and we do everything that we can to make sure that they are properly recognized and appreciated,” Klinger said. “We work really hard in that they also have the union representation in addition to USC Hospitality management. I think at the end of the day, we all worked together and came up with a positive final outcome that works for everybody.”

Fresh Start

Ofelia Carrillo, communications representative of UNITE HERE Local 11 and the main spokesperson for the labor union, works to represent 750 USC staff members. Carrillo said after the five-year contract ended on June 30, 2014, workers truly began to rally their forces.

“I think the agreement that was reached, most people are satisfied with,” Carrillo said. “Most people are happy with. It took a long time to get there. A lot of work behind the scenes had to be done to organize people to get public demonstrations on campus, to get students to align themselves with the workers.”

Even across several decades, many union workers have praised the most recent changes made to the new contract, as the most victorious contract they’ve seen.

“We got raises for all five years of the contract,” Carrillo said. “Total raises over the life of the contract is about $2.95, so within five years of the contract, all of the workers are going to be making about $3 more. In terms of our average, that brings average up to a little bit over it at about $15 hour for non-tip workers.”

The contract reached between the university and the workers reveals the willingness for the university to accommodate workers’ concerns, according to Carillo and many union workers.

“I think the power dynamic has definitely shifted,” Carrillo said. “Whereas before, the workers were kind of on their own, living the day-to-day on the university and in a way felt less empowered. I feel like now regardless of the unique treatment of the workers, the workers are sufficiently empowered with the support of the community, clergy and the students, which are extremely important in the fight. I feel like this alliance is so powerful that they have no choice but to recognize and respect the needs of the workers on campus.”

Arredondo said that movement for higher wages instilled a new sense of hope in many of the workers. She expressed her appreciation for student interaction during the various rallies and protests held, explaining that the labor union could not have done it without the students involved.

“As the days went by, I saw that we had more co-workers join us in our movement, as well as students,” Arredondo said. “That gave us a lot of hope — that this way we could have a better contract, which we did. The students supported us tremendously in every march and rally that we had. They were always there to support us. Sometimes, some of my co-workers could not miss an hour of work, so the support from the students meant a lot. They all work on a budget and they need to support their family. For us to see all of the student support was a joy to all of us.”

Currently, the new contract and the terms of the agreement have already taken effect. Workers have received their new wages, bonuses and health benefits. Though some workers still feel the necessity for an amended relationship between them and university officials, many are satisfied with the changes that have been implemented. Across each department, workers and officials alike both agreed that building strong relationships is difficult within any work environment.

“We are excited that both sides have come to an agreement that both sides are happy with… We are excited that we have come to that agreement and we can move forward and continue to provide the staff, students and faculty of USC with outstanding food and service,” Klinger said.

According to Carillo, there are no more foreseeable rallies and protests regarding details of the contract, but she said that workers are willing to protest if the university does not meet the terms of the agreement.

Pay for student athletes debated

By Darian Nourian

April 15, 2015

Last April, former University of Connecticut basketball player Shabazz Napier caught the attention of the nation when he publicly said that he would sometimes go to bed starving because as a student athlete, he couldn’t afford food. This seemed to be the case despite the fact that Napier led the school to a national championship, and Connecticut continued to make millions of dollars off him in an array of ways, including ticket and merchandise sales and television rights deals. The NCAA tournament alone produces more than $1 billion every year in advertisement revenues, while the NCAA reported a total revenue of $912.8 million in 2013.

“Sometimes, like I said, there’s hungry nights and I’m not able to eat and I still got to play up to my capabilities … When you see your jersey getting sold — it may not have your last name on it — but when you see your jersey getting sold and things like that, you feel like you want something in return,” Napier told reporters in 2014.

Shortly thereafter, the NCAA approved a rule change that would allow Division I athletes to receive unlimited meals and snacks, whereas before, they were limited to three meals per day.

According to a Forbes article listing the most valuable college football teams of 2014, the USC football program ranked 19th overall, raking in a profit of $29 million.

Jeff Fellenzer, a senior lecturer in the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, said the tremendous surplus in funds is related to a growing arms race between competing athletic programs and universities.

“The money that is coming into college athletics into schools is so enormous because of the media rights deals,” Fellenzer said.

The Pac-12’s current 12-year, $3 billion TV deal with ESPN and Fox is worth $250 million a year, and media rights deals altogether generate somewhere between $15 and $20 million annually for member institutions.

Using the tremendous influx of cash into school’s athletic programs as his justification, Fellenzer is a strong proponent for having a student athlete’s “full cost of attendance,” which covers more aspects of the student’s life, covered via an incremental raise of the stipend they receive.

“At the very least, the stipend that scholarship athletes should be increased significantly,” Fellenzer said. “If you’re paying coaches in the millions, building facilities and renovating other facilities, there’s really no way to justify not giving [student athletes] more.”

In June 2014, USC Athletic Director Pat Haden guaranteed four-year scholarships for all football and men’s and women’s basketball players. USC also pays for former student-athletes to come back to school and finish their degrees, which has allowed former football stars such as Marqise Lee and Robert Woods to return to USC during the off-season and finish their studies.

As for the full cost of attendance, USC provides the maximum allotment of health benefits, meals and stipends, per NCAA rules.

The USC Athletic Department generated a little more than $106 million in revenues for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2014, according to the annual Equity in Athletics report, which is filed annually with the U.S. Department of Education as a part of Title IX compliance.

This marked the first time the Trojans ever eclipsed the $100 million mark, which, according to Fellenzer, was because of its lucrative television rights deals with regional and national networks, as well as successful fundraising efforts.

On April 1, the university announced that USC Athletics had reached its goal of raising $300 million for the Heritage Initiative, which is considered the most ambitious fundraising effort in the department’s history.

Emon Saee, a former USC walk-on quarterback who spent three years with the program and graduated in 2013, said that fully covered scholarships are not enough compensation when institutions are making millions of dollars a year off student athletes by broadcasting and selling tickets and merchandise.

Saee is a firm believer that student athletes should be further compensated but thinks that this payment should occur following graduation with money being set aside for them in a trust fund, which would not only incentivize graduation but also prevent players from misusing the money while they are in school.

“A majority of student athletes have no awareness of financial management so therefore, I don’t believe that the stipend while in school should be increased,” Saee said.

He believes that schools like USC are investing a great deal of money and time into student athletes who are receiving scholarships upward of $240,000 over four years, but the main issue is that many of them are not graduating.

Many current student athletes also feel that they deserve compensation.

“[Student athletes] should get paid accordingly to their level of skill and productivity for the university because it’s like having a full-time job,” said a USC student athlete, who wished to remain anonymous to avoid repercussions from the university.

With the ongoing litigation in the O’Bannon v. NCAA case and student athletes attempting to unionize, the current state of amateurism at the collegiate level is in jeopardy more than ever, which perpetuates the ongoing dilemma of whether or not student athletes should be compensated in addition to the tuition scholarships they receive.

Last August, a U.S. district court ruled in favor of former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon, who filed on behalf of the NCAA’s Division I football and basketball players in the class-action lawsuit. The court found that the NCAA prohibiting student athletes to be paid for the commercial use of their likeness violated anti-trust laws and ordered that schools be permitted to offer athletes full cost-of-attendance scholarships and place up to $5,000 per athlete, per year of eligibility, into a trust, for the use of their images.

The NCAA is currently appealing the ruling.

The predicament at Northwestern University goes hand in the hand with the discussion of paying student athletes after the Wildcats football team voted to unionize in April 2014, following a National Labor Relation’s Board ruling that the Northwestern scholarship players were, indeed, university employees and had the right to unionize like any other worker.

USC sand volleyball head coach Anna Collier, however, is not in favor of student compensation.

“Disagree with that 100 percent,” Collier said. “College athletes come here to be student-athletes and notice ‘student’ is the first piece of that. If you are student athletes, you are going to college to get a degree, which you are going to use for a lot longer time than any athletic profession.”

The case is currently in a state of limbo, however, as a decision still awaits on Northwestern’s appeal of the board’s original ruling.

“The issue with unionization is that leadership is such an important part of it and with such a rapid turnover … it would be difficult to maintain union continuity,” Fellenzer said. “The other issue would be that of student-athletes maintaining amateur status.”

In May 2014, Pac-12 university presidents, including USC President C. L. Max Nikias. sent a letter to their counterparts at the other four major football conferences advocating for reform to the current model. In October, the Pac-12 passed sweeping reforms that would improve the overall welfare of student athletes.

The actual pay-for-play model, which carries an abundance of logistical issues such as who exactly will be paid and how much they will be compensated, continues to be up for debate.

Campaign hits goals in final years

By Emma Peplow

April 15, 2015

Design by Samantha Lee

The Campaign for USC, an eight-year, $6 billion fundraising campaign, has revamped and improved the fundraising and university advancement system at USC to garner historic results.

When the fundraising project was announced by President C. L. Max Nikias in 2011, it was the largest fundraising campaign ever attempted in higher education. According to Tracey Vranich, vice president of University Advancement, USC was raising around $284 million a year at the time. Since the campaign has kicked off, Vranich said this fundraising yearly average has increased to between $700 million and $800 million.

“The purpose of something like this is to really raise the bar on the fundraising activity of the university,” Vranich said. “We know we belong in this realm and that USC has the ability, has the prospects, has the branding, and has all these great things that come together and make USC a great place to be and a great place to give back to.”

This past year, USC ranked third in fundraising among American higher education institutions, raising just shy of $732 million, according to Council to Aid for Education’s annual survey. Harvard University ranked first in the survey, raising $1.16 billion with Stanford University following close behind with $928.4 million in fundraising gifts.

Vranich said that the university’s success in the campaign, which passed the $4 billion threshold back in January, centers on the changes USC has made to accommodate increased fundraising. These changes came in the form of hiring more fundraisers, centralizing business operations and even opening two regional offices, one in New York and one in San Francisco. The San Francisco regional office opened in October 2011, just over a month after Nikias announced the historic fundraising campaign, and the New York regional office opened in April 2011, five months prior to the launch of the campaign.

“If we are to fulfill our fundraising ambitions as we enter a historic campaign, it’s imperative that we have a presence on the East Coast to engage alumni and potential donors in their home communities,” Al Checcio, then-senior vice president of University Advancement, told USC News in 2011.

In addition, Vranich said that another component of the campaign that sets it apart from USC’s previous fundraising efforts is that the individual schools were allowed to be more goal-oriented, focusing more of their efforts on the hiring of people solely dedicated to fundraising for individual schools and the drafting of individual fundraising objectives for each school at USC, and less on the tedious business processes involved in fundraising.

“At the schools, you don’t have to worry about processing gifts or prospect research or any of these kind of back office things. That was built centrally and that didn’t exist before this campaign,” Vranich said. “We restructured [University] Advancement to be able to provide that further [aid] to [the individual] schools so they could focus on funding goals.”

According to Vranich, some of the processes that were reformed in University Advancement included the creation of a single online form for all donors to fill out, handling direct mail, direct marketing and depositing, and counting checks, among other processes.

“It’s those type of things that, don’t contribute much to the $4 billion [raised thus far], but they provide those services so the schools can concentrate on major gifts rather than all of these other little activities,” Vranich said. “Those activities need to be done, but let’s hire a major gift fundraiser at Viterbi School of Engineering instead of hiring three people to do direct mail or telemarketing.”

When donating to the campaign, donors are given the choice of giving to an endowment for faculty and research programs, which has a goal of $2 billion; an endowment for student scholarships, which has a goal of $1 billion; academic priorities, which has a goal of $2 billion; and capital projects, which has a goal of $1 billion and includes projects such as the $650 million USC Village, the $20 million Uytengsu Aquatic Center, the $54 million John McKay Center and the $59.3 million Wallis Annenberg Hall, among other facilities.

“The campaign is completely donor-centric,” Vranich said. “The donor gets to decide what is important to them, what they hold dear to their heart.”

Each of the individual schools at USC established a fundraising goal for themselves, in addition to university departments such as USC Athletics and USC Libraries. According to Vranich, the School of Cinematic Arts is within a few million of its fundraising goal of $175 million. Additionally, USC Athletics has recorded its most successful fundraising year in history, reaching its goal of $300 million despite past NCAA sanctions.

USC Athletics is the first program initiative to reach their fundraising goal for the campaign. The initiative focused mainly around student scholarships, the construction of capital projects and the endowment, and was co-chaired by former USC football coach John Robinson and Barbara Hedges, former USC associate athletic director and University of Washington athletic director. The fundraising efforts stressed the building of up-to-date facilities for student athletes, including the John McKay Center, the Uytengsu Aquatic Center and the renovations of Heritage Hall and Marks Tennis Stadium.

The campaign has also attracted well-known public figures that have boosted publicity of the fundraising. Some of these highly publicized contributions to the campaign have included the $70 million gift from Jimmy Iovine and Dr. Dre to create the Iovine and Young Academy, and Arnold Schwarzenegger’s initial undisclosed donation and subsequent commitment of $20 million to create the USC Schwarzenegger Institute.

The Campaign for USC has been the major priority of Nikias’ presidency, launching the fundraising initiative just one year into his term, which began in 2010. Nikias has publicly stated on several occasions that his main goal is to elevate USC in public perception as an elite American universities. From the beginning though, Nikias and the university have viewed the fundraising feat with confidence and optimism.

According to Vranich, Nikias and senior leadership, in accordance with University Advancement, worked together to assess the needs of the university and develop the fundraising goal for the campaign. Where it is often common for higher education fundraising campaigns to be assessed by outside sources that create a feasibility report based on the donor pool and needs of the university and economic climate, Nikias opted to gauge the logistics of the campaign internally.

“Knowing USC, we didn’t spend the money on that feasibility study; we had a pulse on our donors and our potential to begin with,” Vranich said.

Vranich said that the goal of the fundraising campaign was largely determined by what university administrators felt that they could accomplish, and University Advancement remains confident that they will achieve the campaign goals. Though she acknowledges that the remaining three years of the campaign will prove the most difficult, Vranich has no doubt that in the end the donors will pull through. Vranich said the university has forecasted prospective donors, where each donor’s money will go and when the money will come in, giving them a structured plan going forward for the last few years of the campaign.

“Failure is not an option,” Vranich said. “In fact, there is no reason to believe that we won’t be successful. There’s reason to believe that, quite frankly, we will go over [the $6 billion goal] by 2018.”

Through the campaign, USC has been ranking consistently in the top five in the ranking of the most fundraising achieved per year in American higher education. Yet USC ranked 21 in overall endowment last year, according to Forbes. If the campaign is successful, USC would be adding $2 billion to its endowment, increasing it from $3.86 billion to $5.86 billion. Looking at the current rankings for highest endowment, this $2 billion increase would move USC up five spots, putting it just ahead of 16th-ranked Emory University, whose endowment currently totals just short of $3.82 billion, and behind 15th-ranked Duke University, whose endowment is just over $6 billion.

The campaign is set to officially end at the conclusion of the 2018 fiscal year.

First generation: The story of NAI

By Daniel Gavidia

April 15, 2015

Viviana Padilla, a junior majoring in psychology, is a first-generation college student. Her father came to the United States from Mexico when he was 7 years old, and her mother was the daughter of Mexican immigrants. Because of a lack of resources, both of Padilla’s parents did not go to college.

“It’s a new experience for both my parents and I to come into the college life,” Padilla said. “Other students have parents that went to college and know the process, but my parents didn’t have the same knowledge.”

Padilla, aside from being a USC first-generation student is also one of many graduates of the Neighborhood Academic Initiative, an academic enrichment program that has actively challenged USC’s “University-of-Spoiled-Children” stereotype for the past 25 years. Established in 1989, NAI has worked with local schools to gear students toward college and, so far, 100 percent of NAI students have graduated high school, and 99 percent have gone on to college. In total, more than 700 NAI graduates have come out of USC. This success rate, however, has not been easily achieved.

The Story of NAI

NAI candidates apply to the program in the sixth grade. Besides favorable grades, candidates also require a faculty recommendation letter and need to write a personal statement. If accepted, they commit to come once a week to the USC campus for the NAI Saturday Academy. There, they engage in English, math and science courses as in regular school days, plus supplementary SAT preparation courses.

Once NAI students reach high school, the program becomes a daily time commitment. Apart from the Saturday Academy, students must now come to USC for the first two classes of the school day, after which they are taken by bus back to their respective high schools for their remaining classes.

“It is hard to get up for seven years on a Saturday and be here at 7:50 in uniform,” said Lizette Zarate, an NAI curriculum and instruction specialist. “Our kids are working extra hard to make sure that, by the time they become seniors, they are competitive and can apply not just to USC but to whatever college they desire.”

But Zarate, a USC graduate and once a NAI student herself, said the sacrifice is worth more than a ticket to college. Even though NAI graduates accepted to USC receive a full financial-aid package, they also learn what to do once accepted.

“Students end up being able to navigate through a college campus, which is one of our purposes as well,” Zarate said. “They are walking side by side with professors and college students, and it really becomes instilled in them that this is where they belong. So when our first-generation college students get to college, they feel comfortable.”

Zarate explained that NAI students have a strong bond with USC by the end of their seven-year journey. Despite these emotional ties and USC’s generous financial-aid possibilities, however, Zarate said that the NAI is by no means a controlling program.

“That’s what I mean with USC being a good neighbor,” Zarate said. “USC is not saying ‘we’re only preparing you only for USC and once you join in sixth grade you’re signing off your life.’ No. USC is preparing them to go to the university of their dreams, and sometimes USC is not the dream school for some of our kids. By the time our kids finish the program, they are the top students their school and have lots of choices. But they also know that if they pick ’SC, the university will keep its word.”

Giving Back

NAI’s Saturday Academy embodies the popular adage of giving back to the community. Even though all the English and science classes are taught by credentialed teachers from local schools, the math component is taught by USC student tutors. And most of these tutors are NAI graduates.

“This works in many ways,” Zarate said. “First of all, [our tutors] are brilliant, but they also are able to let the kids know that this works, you will get to college, we all did it, you have to keep going.”

Juan Ramirez, a junior majoring in global health, graduated from the NAI program and then became an NAI tutor. A high school valedictorian, Ramirez described that coming to USC was once a remote possibility.

“Before I started with the program in seventh grade, I heard the stories from older kids,” Ramirez said. “They said that some of the kids from the program went to USC. But the neighbors were usually like ‘there’s no way you’re gonna get into USC,’ but I thought that it might be a good way to get into the school.”

Ramirez is a first-generation student. Ramirez, whose mother did not graduate elementary school and whose father dropped out of high school in Mexico, felt in many ways disadvantaged as a USC freshman.

“I used to be the big fish in the small pond,” Ramirez said. “My high school was predominantly Latino. But when I came into ’SC I was the only Latino in my classes. I definitely felt like I wasn’t up to par to everyone else and it took me a while to get used to it. Being a minority is definitely a wake up call.”

Ramirez said that even though Hispanics make up the population majority in California, they only comprise a small percentage of college students.

“You definitely see that in your classes, and especially in science classes, where you are the only one,” Ramirez said. “I wish there were more of us.”

Since his freshman year, Ramirez has tutored math for sixth graders and is now also working directly at the NAI office. He plans to continue giving back after graduation.

“I definitely want to work for nonprofits like Doctors Without Borders and go back to Mexico,” Ramirez said. “I feel like that is where my roots are, and I want to give back to the community where my parents came from.”

Ramirez is not the only one willing to contribute. Jesus Garcia, a junior majoring in computer science and computer engineering, also tutors for NAI. Garcia and Ramirez were high school and NAI classmates.

“[NAI] was very different from what non-NAI students were doing,” Garcia said. “It felt more like a family when going through each of the same classes. We [NAI students] saw each other everyday and helped each other out.”

Garcia is also a first-generation student. Though not the first person in his family to attend university (two older siblings are enrolled at other universities), Garcia is the first engineering major in his family.

“It’s very difficult, and I’m a bit at a disadvantage because I have to go through it myself,” Garcia said. “But I don’t feel excluded. There are lot of people with different backgrounds, and each person has their own thing to put into the table.”

Garcia said that even though his parents dropped out of school in sixth grade to provide for their families, they always pushed their children to take advantage of opportunities and value education.

“I feel like Mexican Americans are disadvantaged in the education world but not intentionally,” Garcia said. “It’s more of the situation of our income. As low-income students we have less resources. High-income students have the money [for] all these different programs. My high school, for example, didn’t offer physics, and many of my peers in college that took physics in high school were thus more familiar with it.”

Garcia also said he appreciates watching new generations of NAI students go through the same things.

“It’s very rewarding to see students understand the material and just teach themselves,” Garcia said. “I see the other students helping each other. They get that kind of mentality with NAI.”

Padilla, another NAI graduate and tutor with Ramirez and Garcia, recalled a similar experience when she was a Saturday Academy student.

“I really had a connection with my tutors in Saturday school,” Padilla said. “They had the experience and made the dream a little more realistic. I’m curious to see [current NAI students’] journey into the program and see where it leads them.”

The USC Experience

Low-income students make up nearly a quarter of USC undergraduates. Furthermore, according to the USC Financial Aid website, more than two-thirds of USC students receive some sort of financial aid. USC students receive more than $500 million in financial aid awards, $360 million of which is solely gift aid.

Zarate mentioned that during her time at USC, she noticed financial disparities with some students. But this, she said, was not a defining factor of her college experience.

“Do I think this is university of spoiled children? No. My experience was phenomenal. I was able to come here and be competitive and felt that I could keep up,” Zarate said. “Financially, I might not have had the means of some of my peers. But in terms of education and social experiences, I feel very grateful to have come here.”

Effects of Village still unclear

By Sonali Seth

April 15, 2015

As cranes glimmer over the site of the upcoming University Village, USC students wait patiently for the behemoth shopping center’s grand opening in fall 2017.

The 2 million square foot project, which is on schedule, is envisioned to dramatically alter the surrounding community, providing housing for 2,700 students and retail space for local residents.

But the space — set to be filled with eateries, shops and retail catering to a middle-class demographic — has called into question its economic feasibility for nearby residents.

“Even though it will make public retail space available, it’s public retail space that is catering to students and the parents who are going to be visiting,” said Karen Tongson, a professor of English and gender studies at USC who also studies suburban culture. “It doesn’t necessarily provide low-cost retail or resources that were available at the University Village when it was a mall.”

The previous space originally opened in 1975, and was purchased by the university in 1999. The 14.6-acre area housed many low-priced eateries and retail, such as Superior Grocers and Burger King. The new Village, in contrast, will include shops such as Trader Joe’s — a grocery chain that has traditionally higher price points than those of Superior.

University officials, however, have maintained that the new Village’s vision has properly incorporated community interests. Craig Keys, associate senior vice president for USC Civic Engagement, described how even before construction began, community input was taken into account.

“In particular, the design has evolved to optimize pedestrian safety, connectivity to campus, and ease of pedestrian traffic through the project,” Keys said.

Additionally, local voice has influenced decisions to incorporate greater parking, streetscape improvements and community access. The project also aims to provide jobs and other services for local residents.

“The construction of the project employs many people from the local area and, once completed, will bring needed convenience and amenities to students and the larger community,” Keys said.

Willy Marsh, building project manager for USC’s Capital Construction Development, stressed that the construction of the Village aims to meet the needs of both the student and external populations by targeting tenants who will cater to student and local communities.

He explained that the finished project should not contribute to a rise in housing prices, a common fear of critics who saw the Village as a potential purveyor of gentrification.

“We’re trying to keep the rents as the same as what is happening in the community around us,” he said. “We’re not trying to use that as a catalyst to make the rents not achievable for local residents.”

Past tenants have expressed interest in returning to the Village, since the demolition of the original University Village displaced their original businesses. Tony Husson, the former owner of frozen yogurt shop 21 Choices at the University Village, said that he would like to find a way to return to the Village, especially because the demolition of the University Village left the issue of a future return to the location unresolved.

“We would have liked if somebody could have helped us with a plan with the future, so that we would have known that in two years we could reopen somewhere in the new Village,” Husson said. “I think the biggest problem was that we left not knowing how we could return.”

Keys said that USC plans to hold a tenants meeting in early May to notify the former tenants about assistance, status updates about the project and leasing opportunities.

Facts & Figures: Tuition Through the Years

April 15, 2015

The rising cost of college tuition is no secret, and tuition trends at USC over the last 50 years are no exception. So how is tuition decided and where does it go? The management of the university makes a recommendation to the Board of Trustees, who then must approve the amount. Because USC is a responsibility center management school, each school collects tuition revenue from its own students and allocates total revenue from tuition as well as other sources depending on its expenses. The planning for 127 budgets begins each year in early January, and the final budget for each school is decided in conjunction with the chief financial officer and the Office of Budget and Planning, overseen by the provost. The largest expense area is compensation for faculty, which can account for as much as 60 percent of each school’s budget.