Recent production doesn’t quite capture spirit of the original

A Chorus Line set itself up for easy billboard praise the moment the lyric “one singular sensation” was included in its signature song, and when it opened on Broadway in 1975, that’s exactly what the musical deserved to be called. Picking up nearly every award that mattered, including a Pulitzer Prize and an embarrassment of Tonys, A Chorus Line revolutionized the stage and went on to become the longest-running show in Broadway.

Not two decades after the musical closed on Broadway, co-choreographer Bob Avian and many of his original collaborators (creator Michael Bennett died in 1987) spearheaded a revival that opened in 2006. Now at the end of its national tour, that revival made its final stop at Hollywood’s Pantages Theatre June 1, where it will stay for nearly two weeks.

Billboards may still proclaim this A Chorus Line a singular sensation, but time has staled that praise, along with the show. There is a lot to cheer for in this step-by-step reproduction, much of which will still resonate with contemporary audiences, but — perhaps inevitably — it isn’t pitch-perfect.

Still, the chance to see this musical, which is as close to the original as we are ever likely to get, should surely be taken advantage of, if only to wonder at how incredible A Chorus Line really could be, and no doubt was in its time.

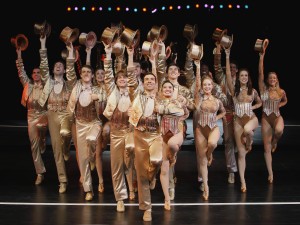

Achieving Singularity — The national touring company of A Chorus Line closes each show with a performance of "One," one of the most recognizable finale numbers in all of musical theater. Photo courtesy of Broadway/L.A.

Played out like a real audition, A Chorus Line puts 17 professional dancers under the spotlight and on the line for a chance to win one of eight coveted spots in an unnamed new Broadway show. For two hours, these men and women struggle with their craft and with themselves as they try to impress the show’s director and win the job. The stage is bare. It’s only the dancers lined up center stage, the director’s disembodied voice and the iconic, mirrored panels in the background.

In 1975, the premise was irresistibly original. A self-reflexive exercise that captured the essence of desperation and self-doubt, the show gave a voice to generations of people either afraid or unable to face up to who they were and master that identity.

Today, that premise has been somewhat spoiled by our overconsumption of reality competitions like American Idol and So You Think You Dan Dance, which bear more than a passing resemblance to A Chorus Line and might be said to have their origins with it. Those kinds of shows are successful in large part because we derive some kind of vicarious pleasure through watching others make it or break it. But the chance of being privy to these experiences no longer has that same taste of privilege or intimacy, because we can see it every day.

Of course, we prefer to think that A Chorus Lines remains a much more powerful experience than American Idol, because it’s immediate. To a certain extent, that’s obviously true, and the show has the potential to plumb far greater depths of emotion. But, painful though it is to concede, the sentimental backstories of each of these performers — some of the men have sexuality issues, some of the women have daddy issues — are not unlike the prepackaged one-minute clips on So You Think You Can Dance that evoke a similar pathos.

The frankness with which the show examines sexuality is certainly admirable and still relevant, but the other issues are less startling. However, “At the Ballet,” sung serviceably, if not spectacularly, strikes a painful note that no amount of American Idol packages can approximate, and speaks beautifully to that fantasy realm to which all dreamers escape when their real life becomes too difficult to bear.

Each of the roles in A Chorus Line is based on the life of a real person, many of whom actually starred in the original production as versions of themselves. Being an extra level removed from reality by having actors play real people perhaps explains why some of the characters’ stories don’t seem real enough. The most believable stories are the least serious — vertically challenged Connie (recent USC graduate Catherine Ricafort, cute as a button) coping with her petite stature, tone-deaf Kristine (Hilary Michael Thompson, wonderfully gawky) trying and failing to hit a single note in “Three Blind Mice,” and augmented Val (Kristen Martin, a standout) singing about her newly augmented features in “Dance: Ten; Look: Three,” pure comedic gold.

The other women are mostly hits, with a few minor misses. Ashley Yeater’s Sheila — the self-proclaimed woman of the group — has attitude to spare, nails her priceless one-liners (“Can the adults please smoke?”) and mostly gets Sheila’s emotional past.

But it’s the stunning Rebecca Riker as Cassie, the closest there is to the female lead, who steals her scenes. She acts with her whole body and really understands her character, a woman who tasted stardom, tried to capitalize on it, failed and must now return to square one but is somehow content to be there. Her complicated relationship with Zach, the show’s director (Derek Hanson, unfortunately as dull as dishwater, but an exquisite dancer), is handled expertly. Only in her solo dance sequence does Riker not totally physicalize the music and her emotions, but the performance is top-notch.

If Cassie is the most important female, then Paul (Nicky Venditti) is the most important male. Troubled and fragile, Paul might be the emotional centerpiece of the show — his speech on growing up gay a dramatic masterpiece. The so-called “Paul monologue” has the potential to be shattering, but Venditti’s reading is unfortunately merely touching. He starts at fever pitch, leaving him no place to take the speech emotionally, and punctuates his manic recitation with sharp, forced half-laughs that might have proved effective if employed sparingly but in such excess simply grate on the ears. For a superb interpretation of the speech, seek out the excellent 2008documentary Every Little Step, which chronicles the casting process of the 2006 revival, and flip to Jason Tam’s audition. Be sure a box of Kleenex is on hand.

Venditti’s strained effort to capture a moment’s worth of true reality seems to be the problem with the entire show. If it were a show about a bunch of make-believe characters trying to overcome personal obstacles, it would be a total success, but the trouble is that it’s not. The mythos of A Chorus Line, but more importantly its firm basis in a stark, unglamorous reality, makes it impossible to forget that this story is supposed to approximate real life, and when it doesn’t, no matter how fine the dancing — which, it should go without saying, is spectacular — or the singing or the acting, we’re left feeling incomplete.

At the end of the show, when Zach announces his casting for the eight spots in the chorus line, there should be palpable anticipation in the air, but there isn’t. Nothing feels at stake. For all our reveling in these men and women’s formidable physical talents, somewhere along the line we stopped caring about their emotional struggles with identity, self-worth and regret, which in a show like this must be genuinely and unabashedly front and center.