Baptism by fire

On April 29, 1992, Los Angeles erupted.

Large chunks of the city were shredded and set aflame as Angelenos clashed with police officers and violence spread throughout the city. Witnesses compared the looting, burning buildings and shootings in South Central to a war zone — and the area immediately surrounding USC was in the heart of the chaos.

The riots began when tensions between the black community in South Central and LAPD were stressed after a video of officers beating Rodney King — a black man — during a traffic stop was nationally broadcast. The officers were put on trial and acquitted — sparking the violent eruption of the riots, many of which took place in the area around USC.

The university, however, sustained only minor damage. Although thousands of Angelenos were injured and 53 died, only four students were injured and none were hospitalized. Twelve thousand people were arrested, seven of them USC students. Students and buildings were robbed, but USC was relatively untouched compared to the estimated $1 billion in citywide property damage.

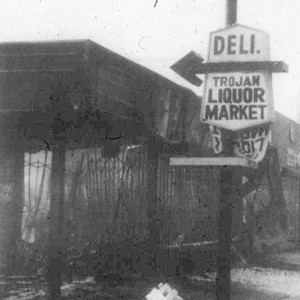

Complete coverage · Though the Daily Trojan had ended production for the semester, it printed a special edition covering the 1992 riots to inform students of the events — including rioting and looting — that were occurring. | Daily Trojan file photo

Still, USC went into lockdown, enforcing the 9 p.m. citywide curfew and adding measures to protect students. The Row and much of off-campus housing was evacuated, according to Daily Trojan reports. Students in Parkside Apartments and the North University Park area were moved to Birnkrant Residential College, the Lyon Center and Webb or Fluor towers.

An emergency earthquake drill had been held the week before the riots broke out, and the Emergency Operations Center was utilized to deal with the disarray caused by the riots. The Division of Student Affairs was open 24/7 to field calls.

A non-university man was shot in the leg on campus near Parking Structure A, and when an ambulance failed to arrive, university security had to commandeer an escort van to take him to California Hospital, according to a Daily Trojan report.

Former USC President Steven B. Sample rode along on a routine security patrol on the second day of rioting with a police lieutenant, who told the Daily Trojan that Sample’s eyes were “as big as his head.”

The university also had very visible security on and around campus. Students and alumni volunteers helped patrol buildings, USC security officials worked double shifts, LAPD officers ate at Everybody’s Kitchen and the National Guard was headquartered at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

“It was not simply a miracle that USC came through unscathed; rather, it was in large part because of the hard work and dedication of thousands of individuals who love this university and the community of which it is a part,” Sample said in a letter published in a special edition of the Daily Trojan.

This sense of community helped the university endure the riots and helped shape it after the violence ended.

Reverend Cecil “Chip” Murray, now an adjunct professor in the USC School of Religion, served as reverend of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church for 27 years, including during the riots.

“When the burning, the looting and the rioting started, USC was exempt because the community considered it a part of it,” Murray said. “USC did not pick up and run from the community. It did not isolate itself. It said, ‘We are part of the community; it is part of us.’”

Other schools did not do the same when faced with similar crises. Pepperdine University, now located on the bluffs of Malibu, Calif., once sat in South Central Los Angeles. After the Watts riots of 1965 broke out near the campus, deeply rattling the Pepperdine community, administrators began to look for new locations for the college. Two years later, the land in Malibu was offered to school officials, and in 1972, the new campus opened.

“USC could have found another place. It could have found another fortune among the most fortunate,” Murray said. “Even if it had chosen to stay as the impoverished communities began to surround it, it could have built walls — not just mental, but physical walls — to keep people out.”

Murray said this more welcoming mentality also deters criminals from targeting the university now.

“Even today, the crime rate — you have some criminals and you get reports from our public defenders here on campus — it could be 20 times worse,” he said. “But the image is such that we welcome free thinking. We welcome free thinkers. We welcome all who are within our reach.”

After the riots, Sample offered use of USC’s facilities and services to the city in its efforts to rebuild Los Angeles, which were headed by Peter Ueberroth, a lifetime member of the USC Board of Trustees.

“Let me encourage all of us to share our good fortune and deliverance by lending a hand to those of our neighbors who have suffered directly from this tragedy,” Sample said at the time. “USC has played an integral part in the life of this city for more than a century, and I expect we’ll play an even more important part in the years immediately ahead.”

At the time, USC was involved in more than 60 different outreach programs, reaching nearly 250,000 children yearly. That number would continue to grow under Sample’s leadership. The Neighborhood Academic Initiative, which gives local children the chance to earn a full scholarship to the university if they complete a six-year academic program on campus, and the Joint Educational Project, which pairs university students with local children as mentors, are both still active.

Murray said that programs like JEP continue to make USC accessible, a key aspect of making the university a neighbor in the community.

“The fact that, in the poorest sections of South Central, when I said, ‘I’m out at USC,’ I hear, ‘Oh yeah, yeah — that’s our school.’ From a person who may not have completed seventh, eighth grade — ‘our school.’ It’s because ‘our school’ reaches out,” he said. “If we were not reaching out, this would be an island mentality because people would be awed by this world university and not even come to the campus and come on tours. The campus doesn’t wait for the people to come to it — it goes to the people.”

USC also created its own volunteer organization after the riots, the Coalition in Response to Civil Unrest, led by Professor of Religion Alvin Rudisill. The coalition submitted a report on improving race relations in the community on June 23, 1992 — about two months after rioting ended on May 4, when the city curfew was lifted.

The report gave two recommendations: to promote discussions, dialogues and lectures about the community, and to encourage diversity. It also noted that USC faculty should incorporate city issues into their courses.

Most students don’t remember the time when these riots happened — many freshmen were born after they occurred. There have also been myriad changes in city policy since 1992, which has altered the conditions that led to the riots.

Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism Professor Judy Muller covered the Rodney King trials and said the mentality of the police force helped create the tension that sparked the violence.

“Back then, police had a mentality of us versus them. They went into these neighborhoods like it was a war zone — there was no community policing,” Muller said. “Now, that’s all changed. Today, if something like this happened, I don’t think you’d see that kind of an eruption.”

Murray said his experience in Los Angeles has led him to the conclusion that USC’s inclusive philosophy has been a leading factor in the university’s rise in national and international standings.

“Living in the south of Los Angeles, and talking with the people of all levels … being minister of First AME church for 27 years … you get to hear a lot. I am not certain that I have ever heard negative expressions regarding the University of Southern California,” he said. “There obviously had to be a time in its earliest days when it was enshrouded with racism and discrimination [but] in the last 25-30 years … we have seen firsthand the profits of being inclusive rather than being exclusive.”

“We could never walk backwards,” Murray said. “We can only go on.”