How I actually started learning to speak Spanish

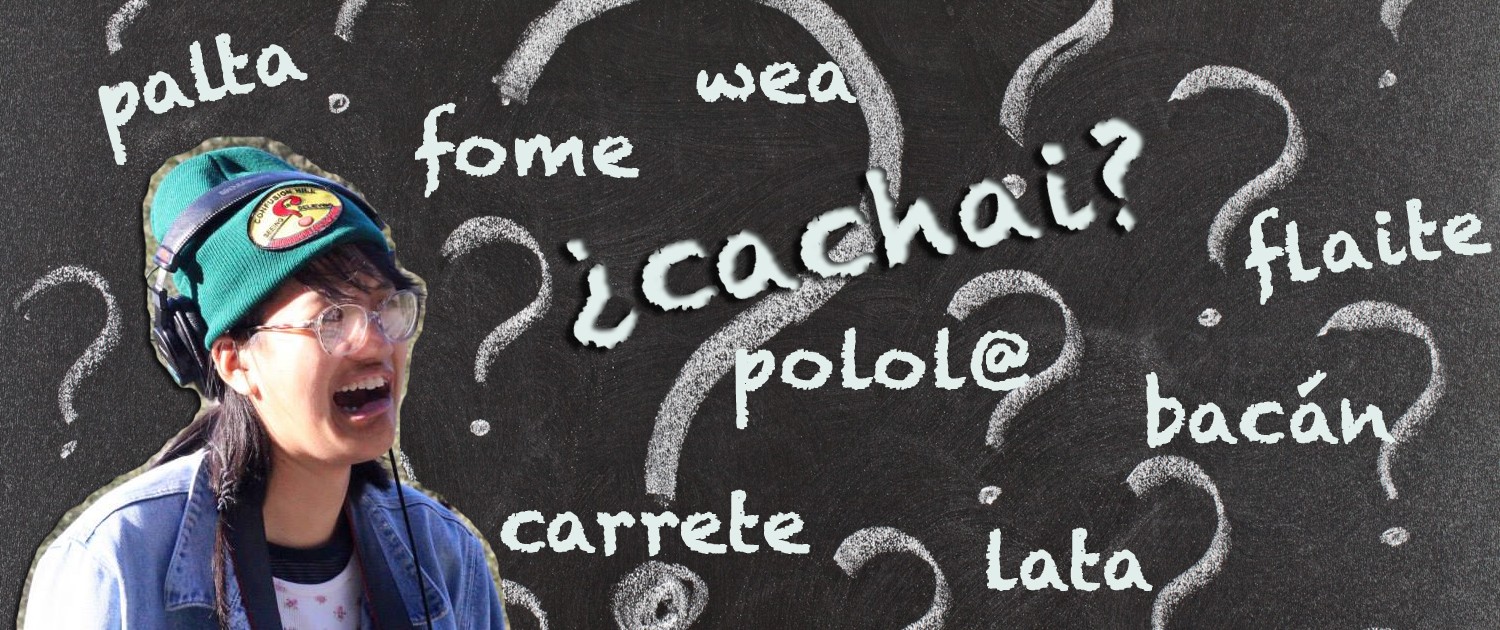

After years of Spanish classes, I still felt like I couldn’t actually speak any Spanish when I arrived in Chile. During my first week in Santiago, people were constantly like, ¿me entiendes? ¿Cachai?, using words I’d never even heard before, like paltas (avocados), carrete (party), fome (boring) and variations on wea which I still don’t quite understand how to use. It was so bad that I immediately panicked and emailed my academic advisors about not being able to pass any classes.

My trouble with learning Spanish has less to do with the amount of time dedicated to formal training and more to do with my intense awareness of how people perceive me when I speak (as a queer Asian-American woman, as the first child of working class war refugee immigrants, etc.), compounded with my immense shame about how I’m dedicating time to learning yet another language that’s not mine, while I still struggle to speak to my mother in a language that she knows.

Finally, though, I got over it by using a superficial social mobile app where everyone is judged solely based on how they’re perceived through five photos: Tinder.

I’m not kidding.

It was something about the low stakes of having the same mindless conversations over and over with random people I didn’t know in Spanish that helped me visualize words and reinforce sentence structures I already knew. Then I expanded vocabulary by using phrases people said to me with other people. I even worked up the confidence to throw in jokes sometimes.

Okay, I’m sort of kidding.

Tinder was a part of it. So was being enrolled in a Spanish-speaking university and living in South America in general. But it also had a lot to do with being in a place where the social dynamics around language are different.

Growing up in Los Angeles, I realize that knowing Spanish wasn’t often seen as a sign of multilingual success despite systematic racism; it was attributed to the fact that you go to a predominantly Latino public high school, an indication of your socio-economic status, and a twisted way people determined which opportunities would be available to you.

My experience with language in the United States has been one with high stakes such as these, deeply entwined with how I’m judged and valued as a person. White people who know multiple languages are rewarded for being cultured, while people of color who hold onto their ancestral tongues are shamed for not assimilating quickly enough. For the price of gradually forgetting my first language and not being able to ever fully communicate to my own parents, I’m offered the opportunity of social mobility, the American Dream.

I’m not saying that Chile doesn’t also have its own complicated language landscape, but my stakes in this landscape are a little different, allowing me to start learning Spanish in a way I had not been able to do before.