Academia Nuts: Jody Armour — Exuberant Nappiness

For the last few weeks, the dialogue surrounding race and social justice in the United States has been reduced to a single question, framed as a black-and-white (or maybe a black-vs-white) issue: do you support Colin Kaepernick and his decision to kneel during the Star Spangled Banner, or is ‘disrespecting’ the American flag a hostile act of treason? When complex ideas are sliced into 140-character one-liners, nuance is often the first casualty. This is debate in 2016 — largely unproductive, ill-informed, often times rude. Still, Kaepernick has achieved remarkable success in starting a national conversation, perhaps sparking even more outrage than the filmed police murders of two black men.

It is because of Kaepernick’s celebrity that the media has exploded with his story. But while he may be the most recognizable, he’s not the only afro-sporting black man fighting for change in our country. One such activist, blessed with extravagant nappiness, is USC’s Jody David Armour.

Jody is the Roy P. Crocker Professor at the Gould School of Law. A 20-year faculty member, he regularly teaches torts and criminal law. I was recently invited to Armour’s home to observe his law-school seminar, ‘Race, Stereotypes and the Rule of Law.’

The door was open when I arrived, and my knock was greeted by a booming invitation to “come on in!” Jody was tidying up around the house, gliding from room to room, busy but not harried. He showed me out to his backyard, and returned to his preparations.

The house sits atop a hill in View Park. When incorporated with Baldwin Hills, Windsor Hills and Ladera Heights, this neighborhood makes up the “largest contiguous middle to upper-middle class black area in the nation,” Professor Armour said. Some call it the Black Beverly Hills, and perched on its peak is Jody’s home.

From the backyard, I could see the entire L.A. Basin, complete with an unobstructed view of downtown, and a sharp glare from the setting sun reflecting off smog. There are a couple tables on the patio area, and a pool. It looks perfect for a family BBQ; I would almost call it *gasp* suburban.

That was my first impression. It was quickly corrected when I noticed the three dinosaur sculptures, each in a different corner of the yard. You know the giant dinosaurs out in Palm Springs, the ones in the Pee Wee Herman movie? They look like those, only on a smaller scale. No backyard can be suburban when it’s home to a T-Rex, Velociraptor, and Triceratops.

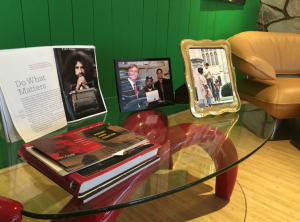

I got the chance to look around the living room while waiting for the seminar to begin. Jody’s personality is reflected in the decor — an eclectic arrangement of art, architecture, and design — a collection that both highlights and shatters stereotypes. Yellow and green walls are lined with paintings of athletes and musicians, portraits of influential black figures. Sitting in front of his stone fireplace is a collection of trophies; accolades earned in various sports by his three sons. On the coffee table, next to a model skull of a saber-toothed tiger, is an assortment of mugs, bottles of lemonade, cranberry juice, and a box of Triscuits — drinks and snacks for the upcoming discussion.

The small row of books on display in his living room showcases Professor Armour’s intellectual pursuits. Among the dozen or so titles: Philosophical Investigations (Jody tells me that the author, Ludwig Wittgenstein, is “the lawyer’s philosopher, par excellence”); Ideals, Beliefs, Attitudes & The Law; Racial Paranoia; Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

This is the house of an academic, an artist, a lawyer, a philosopher, a black man.

While observing the seminar, I was struck by Jody’s laid-back style of teaching. He sits in a black armchair, feet kicked up on the table — he would be slouching, if he weren’t so tall.

Half of the class meeting was spent on introductions — every student shared their name, year (all 2Ls and 3Ls), and hometown; what normally seems like a colossal waste of time was turned into 20 different teaching opportunities by Professor Armour. “Oh, you’re from Chillicothe, Ohio? Hold on, here’s what’s deep about that, I visited my dad in prison in Chillicothe, Ohio.”

Jody attributes much of his interest in the law to his father’s incarceration for the possession and sale of marijuana — 22 to 55 years. While incarcerated, Fred Armour learned the law “from the warden’s own books” and eventually won the case ‘Armour v. Salisbury,’ which Jody now teaches in his criminal law class. He is intimately familiar with the effects of mass incarceration, as both the son of a ‘criminal,’ and a legal scholar.

Jody’s upcoming work, N***a Theory (seen in part here), forms at the intersection of his personal life experience and his years as an academic, professor, and public intellectual. N***a Theory is a response to those who embrace a politics of respectability, people like Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and comedian Chris Rock.

Jody’s upcoming work, N***a Theory (seen in part here), forms at the intersection of his personal life experience and his years as an academic, professor, and public intellectual. N***a Theory is a response to those who embrace a politics of respectability, people like Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and comedian Chris Rock.

Those who espouse a politics of respectability hold that ‘well-to-do’ black people should disassociate themselves from black criminals, thus protecting the reputation of the ‘good black people’ while denigrating and other-izing, or, as put by Professor Armour, “niggerizing,” ‘bad black people.’ They create, to quote Armour’s work, a “litmus test” for the stark definition of ‘good negroes,’ and ‘bad negroes,’ a distinction based solely upon one’s criminal activity.

The politics of respectability says that to be good is to be law-abiding, to be bad is to be a law-breaker. Such a philosophy grants state lawmakers and enforcers the power of moral judgment, creating a mechanism by which one can evaluate a person’s moral worth by their accordance with the law.

Of course, this is a fallacious line of thinking. “Highly disadvantaged people do commit a higher rate of crime [than relatively privileged people], that’s a statistical fact,” Professor Armour said. So it goes something like this — being black in America brings along with it a certain set of structural, systemic disadvantages in socioeconomic status and treatment under the law (disadvantages that can be directly traced to slavery). Being highly disadvantaged leaves one at higher risk for committing crimes, and once someone has committed a crime, we label them ‘bad,’ or ‘n**ga.’ So an entire group is born into a system ready to strip them of moral worth and throw them in prison. And still, we tell Kaepernick to rise.

In the antebellum United States, it was slave-status that marked a black person as unworthy of humane treatment; today, Armour contends, it is a label of criminality that allows people to turn their backs on disadvantaged blacks.

The inspiration for the title of Jody’s work comes from the politics of respectability as presented by Chris Rock in his most famous stand-up routine; he tells the crowd, “I love black people, but I hate niggas!” As one whose chief benefactor has been white privilege, my first question for Jody was one of both substance and necessity — “How should I refer to your work?”

“The n-word,” Professor Armour began, “is no different than any other linguistic or non-linguistic form of communication, its meaning is mutable like the confederate flag, they both have deep roots that run into a racist American past… the difference though is blacks have not appropriated the confederate flag in the way they have appropriated the n-word.”

Because of the linguistic appropriation in the black community, Armour said, the n-word has been “inverted and transvalued [such that] it can be used with irony.” Meaning, as Jody’s favorite philosopher, Wittgenstein, tells us, is use. When the n-word is used by a member of the black community, it is a radical disavowal of what the word has historically meant. When used by someone outside the black community, it retains its status as a “blood-soaked epithet,” and with it the vestiges of slavery and racism, hate and disgust.

Of course, some have trouble with this perceived monopolization of the n-word: ‘free-speech activists’ and white dudes who don’t like being told what to do (I am a recovering member of this particular faction) make up the preponderance of this group. Jody knows this, and doesn’t presume to tell anyone what they can and can’t say in the privacy of their own homes, or in the car with the radio blasting. But, he says, when you use it, “You [should know] you were running a risk… it’s a word that wounds, and when it does, [don’t] act hurt or surprised or upset and start talking about some double standard.”

Of course, some have trouble with this perceived monopolization of the n-word: ‘free-speech activists’ and white dudes who don’t like being told what to do (I am a recovering member of this particular faction) make up the preponderance of this group. Jody knows this, and doesn’t presume to tell anyone what they can and can’t say in the privacy of their own homes, or in the car with the radio blasting. But, he says, when you use it, “You [should know] you were running a risk… it’s a word that wounds, and when it does, [don’t] act hurt or surprised or upset and start talking about some double standard.”

But while this word can only be transvalued by the black community, its presence is ubiquitous in our cultural zeitgeist, particularly in hip-hop culture. It’s utterance is reserved for African-Americans, but everyone hears it. It makes people uncomfortable, and it should — that’s one reason why it’s a staple in rap music, and it’s also part of the reason Professor Armour brings it to academic discussions. In his mind, the n-word, like all words, is a “cultural resource,” and can achieve great effect when used properly.

That is not to imply Jody is callous about his diction — as a lawyer and philosopher, precision of language is one of his daily concerns. When I asked him if he ever felt conflicted about using the n-word, he told me, “You know, I’ll say the n-word, I’ll say nigga, because I’m coming at it from a different position in terms of social stratification, vertical relationships between people, oppression and dominance.”

There are words that Professor Armour readily admits are not available for his use. In this respect, the n-word is rather analogous to b**ch, an insult historically directed at women. “I am in a privileged gender,” he said. “I am not going to appropriate a word used against members of another gender just because some members of that other gender have decided to adopt the word themselves and put it to [their] own purposes. I’m not gonna say, ‘Just because they use it now I can drop all the b-bombs I want.’ No, it doesn’t work like that, that’s my sense of male entitlement.”

It is clear that much of a word’s meaning is influenced by the identity of its speaker. So how do we know what identity is occupied by whom? For African-American identity, there is no escaping the historical legacy of slavery. “When it comes to blackness in America, you always come back to the auction block,” Professor Armour told me. “That is what makes you black. What makes you black is you could be put on an auction block, and auctioned off as chattel.”

While this may be the essence of how blackness was formed in America, Professor Armour is keenly aware of the nuance and contingency of social identities. When I told him that my ethnic background is half-caucasian, half-latino, but that I feel disingenuous identifying as anything other than ‘white,’ he commented, “Social identity is not something you’re necessarily born with, but something you perform.”

Blackness, he elaborates, is not a function of biology, but a complicated intersection of experience, circumstance, self-identification, historical context, and the list goes on. To think of blackness as primarily formed by skin color, for example, is a broad erasure of many seminal black figures in American history. “You aren’t going to go very far in black experience and black history if you start excluding people who have any white blood in them.” Armour points to such luminaries as Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. DuBois, and President Barack Obama as undeniably black people who are light-skinned and biracial.

There is, of course, a phenotypical association of dark-skin with blackness, and therefore an association with dark-skin as a marker of moral depravity, if seen through the lens of respectability politics that Armour seeks to shatter. And this association is not only confined to socioeconomically disadvantaged blacks, but attached to any who appear to fit a certain mold. “Because they are conspicuously black, let’s say, discernibly black in terms of social phenotypes and stereotypes about phenotypes,” Jody said, “[black people] have to deal with discrimination on the basis of their black appearance. That’s where racial profiling kicks in.”

As a black man with a glorious afro, Jody has a wealth of experience when it comes to being profiled. On multiple occasions, his “exuberant nappiness” (great name for a funk band) has resulted in his being perceived as a homeless man, or a criminal. When he first started growing out his hair, he had “students remark that it was ironic that [he teaches] criminal law, and [he looks] like a criminal.” When he was later told by “some downtown attorneys” that his appearance was unprofessional, Jody told me, “I said as a self-conscious matter, that I am going to adopt this hairstyle, this follicle fashion, in defiance of those stereotypes themselves, as if you can’t be a law professor and have an afro.”

Since donning the afro, Jody has been hassled by guards at JW Marriott who assumed he was a homeless person, and regarded with suspicion by sheriffs at his own front door. “My afro became my hoodie,” Armour said. It’s a hoodie that he can’t remove when he teaches a class, or speaks on a panel — not that he would want to remove it, anyway.

For Jody, the afro is not solely an act of defiance, a means of showcasing the broad strokes of racial profiling; it is also a “celebration of the African-American soul, pure and simple.” When talking about his hair, I asked if he could elaborate on how he has ‘deliberately caricaturized and cartoonized himself through his appearance.’ This was one of a few times when my own questions were laden with the implicit biases and racial stereotypes that I was asking about — there was my white privilege, assuming that the only reason he wore the afro was to say ‘fuck you’ to the establishment.

He told me to go check out his twitter profile picture, his senior portrait from high school. “We didn’t consider it a caricature back then in the 60s and 70s,” he said. “Brothers and sisters were rocking fros, there was nothing caricature about it. You know, happy to be nappy kind of mentality.”

Nevertheless, Professor Armour’s donning of the afro today is an inherently political act. “I continue to wear it proudly, like Colin Kaepernick rocks his fro, like a bat signal of solidarity for victims of racial oppression,” he said.

I told Jody that he would be a great character in a graphic novel — Afrolawyer.

He chuckled, and, quoting Brooklyn hip-hop group X-Clan, spit a couple lines:

“‘Walk in the light of the moon but I never been a Batman,

African call it Blackman.”