Should USC have political parties?

A large crowd congregates in the center of UCLA. It’s early May, and emotions run high as the campaign season for Undergraduate Students Association Council elections draws to a close. Students wait in suspense for the announcements of the results for council positions. One group of students, donning Bruins United shirts, cheer with glee, unable to hide their visceral excitement. Others wipe away tears and exchange conciliatory embraces.

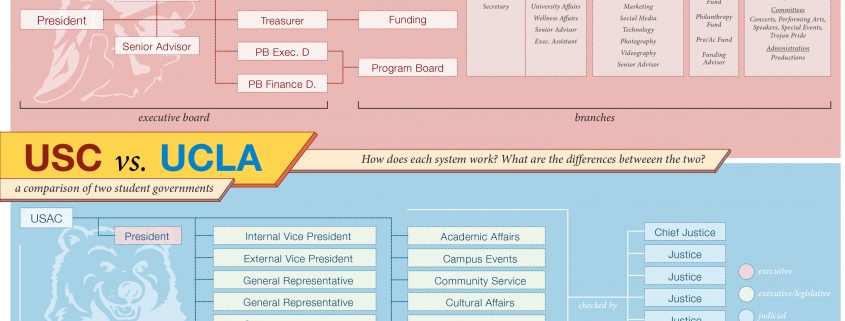

Welcome to campus politics at UCLA, where student government’s identity runs strong in the form of a party system. These student political parties, called slates, have dominated the UCLA political sphere with their decades-long roots. Last year, Danny Siegel, the current president of USAC, the UCLA equivalent of Undergraduate Student Government, clinched the presidency with more than 10 percent of the vote in an environment that he said fosters intense competition.

“The way that elections work at UCLA can make them a very high-stress situation,” Siegel said. “You want to be promoting your candidacy and your slate to as many students as possible, under fast-paced, well-regulated conditions. Every vote counts, so you really want to make your case to anyone willing to listen.”

Siegel represented the Bruins United slate, a juggernaut party that swept nine out of 13 council positions in addition to the presidency last year. The slate formed in 2004 as a conglomeration of different groups on campus — Bruin Democrats, Bruin Republicans, various Greek organizations and Jewish students. Since its inception, Bruins United has remained a stalwart in USAC, though it has been challenged by other slates, most recently by Waves of Change.

“In the process of trying to reach as many students as possible on campus, I would say that the slate system creates more competition, especially at UCLA,” Siegel said. “It’s so ingrained in our system, and it just makes sense to have people who want to champion the same values as you. They’re your governing coalition, and you’ll work together on different projects, advocacy efforts and go to our weekly council meetings and support each other’s initiatives.”

Comparatively, the fervor for campus politics at USC seems tepid. Last year, in the USG elections, less than 20 percent of voters — down 39 percent from the previous year — cast ballots for their student representatives. If voter turnout is any indication for student engagement on campus, adopting a slate system is a possible remedy, according to USAC External Vice President Rafael Sands.

“I’m surprised it hasn’t happened yet at USC,” Sands said. “When a lot of students get together, they should realize that simply by partnering up and building a coalition around shared values, they will able to reach a lot more students.”

USG President Edwin Saucedo isn’t completely convinced that USC should embrace a slate system. According to Saucedo, slate systems, with clearly delineated allegiances, bar outsiders from entering student government.

“I think it’s a bit of an unfair system because with such deep party establishments, it creates barriers for people who want to be involved with student government to come in. If you look at Bruins United, it has been relatively uncontested for so long,” Saucedo said. “Whereas this year, in the USG elections, we have a ticket with no USG experience, but that doesn’t create a barrier for their race.”

Plus, as Saucedo points out, recent changes to the USG elections system have allowed more students to run.

“Last year we switched from having constituencies for senators to just being anyone can run for any office,” Saucedo said. “There’s no greek, commuter or residential [constituencies anymore].”

The USG system now features the election of independent tickets and 12 senatorial candidates every year. For USG president and vice president tickets, Saucedo thinks that election season allows candidates to collaborate with their running mates on platform points.

“As the presidential ticket, you’re running with a vice president candidate that you’ve hand-picked,” Saucedo said. “When you pick this person, it means you’re willing to work with them, and you’re setting up both of your successes.”

But former USG President Rini Sampath points out that a slate system could help students finance their campaigns, which is an important aspect of running for office.

“At USC, we’ve created a reimbursement system personally,” Sampath said. “It ended up costing us a lot of money for student government when one of the tickets backed out after we had already funded their campaign. You don’t want finances to hold any students back, and that’s why political parties and slate systems are able to fundraise and raise money in order for them to run an effective campaign.”

She also thought that the slate system had some other upsides. According to Sampath, from the USC lens, political ties could be a contributing factor to the level of engagement in UCLA campus politics.

“Maybe, political parties on these campuses are able to reach students at that level — at that visceral level — and bring students to vote,” Sampath said. “There’s also, of course, to some extent, loyalty to a certain side.”

Though Sampath sees drawbacks, she thinks that the slate system could motivate long-term interest in student politics.

“I think that if we were able to create some kind of foundation of knowledge to be passed on each year, that’d be great,” Sampath said. “It would actually create an even playing field and let everyone have a shot to run for president.”

In addition to passing on knowledge from one incumbent to another, Siegel said the slate system increased responsibility for elected leaders, holding them accountable to meet all of their platform points.

“The other party will like to try to hold those who won accountable,” Siegel said. “Because when you’re in the opposition, you want to magnify it and amplify it to boost your chances in the next election cycle, which is just a normal part of politics.”

But Siegel and Sands also acknowledged flaws in the USAC government system. According to Sands, slates create polarization and may not engage everyone on campus.

“It’s surely not perfect, and it’s very hard to get all the students involved,” Sands said. “But I think the nature of having a student government with a competitive environment is people challenging others to come up with better ideas and prove themselves.”

Hahney Yo, director of finance and administration of Program Board, has recently modified the current USG structure to improve the way the organization is run.

“The new structure would help aid USG transparency and increase internal communication with everyone,” Yo said. “That’s the problem USG has faced for so long, because if you think about it, the top manages 120 people.”

Yo proposed a restructuring of leadership within the five branches of USG. The potential new USG structure would see the chief of staff champion the advocacy branch, allowing the president and vice president to focus more on their own initiatives.

“It won’t ever be perfect, but I don’t think any form of government will ever be perfect,” Yo said. “We can only ever work on creating better systems as we see things work and not work each year.”