COLUMN: The Great Wall’s identity crisis

I visited Beijing with my family when I was 12. My parents are from Taipei, but the mainland is where my ancestors lived. Unlike the democratic Taipei, which my sister and I had become familiar with after multiple trips, Beijing was expansive and smoggy and unfamiliar to me. Police stopped a woman on the street just to search her bag. The computer in our hotel lobby would not allow access to Facebook.

But what struck me most about our visit to Beijing was how Chinese tourists treated foreigners or at least, the visibly foreign: an English family at the Forbidden City, a group of white Americans at the Great Wall. Other visitors, all Chinese, seemed to flock over them: The tourists were exotic and enticing, and some even asked for pictures with them.

Of course, my sister and I were foreign, too; we were raised in the Midwest, with accents weaving through our Mandarin as thick as blood. And yet, no one asked to take pictures with us. No one thought to look our way.

Asian culture is obsessed with white beauty, but even more pervasive than that is the desire for appreciation from white Westerners. Colorism is deeply embedded within Asian cultures; it is apparent in the number of skin-lightening creams lining drugstore shelves and the inane fear that consuming too much soy sauce will make your skin grow dark. Lighter is beautiful. White is the jackpot.

At 12 years old, I didn’t need to be told this. I was growing up round-faced and Asian American in a predominantly conservative neighborhood in Cincinnati. My high school just didn’t have any kids who looked like me. It seemed like the girls who earned boyfriends all had flat stomachs and big eyes and light-colored hair. I specifically remember growing up, at four or five or six, thinking that one day I would be able to stroke my own blonde hair, falling in waves around my shoulders.

At the time, I could imagine no other standard to hold myself to.

No matter how far I’ve traveled, it seemed like this iron tenet would not break: Things are better when white people do them. It’s why China rose up in a frenzy after President Donald Trump’s granddaughter sang a song in Mandarin. It’s why the upcoming movie The Great Wall, starring Matt Damon and set in ancient China, is reviled for whitewashing in the United States and celebrated on the other side of the globe.

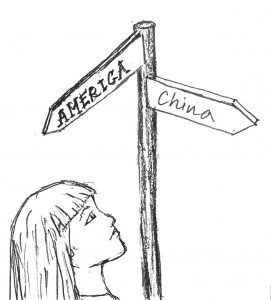

When you’re Chinese, it feels affirming to see a blockbuster set in your country starring a white lead. But when you’re Chinese American, it gets complicated.

Of course, this Chinese American girl grew up writing furiously and watching movies hungrily, and she moved out to Los Angeles to pursue her dreams through film school. The scripts I write today are about women and people of color, and I carry the fullest belief that expanding our scope of who belongs in the movies only broadens the possibilities of our art. By nature of my own identity, I have strong opinions about The Great Wall and Damon — who seems blissfully ignorant of how diversity and progress works in filmmaking. But not all of these I can reconcile with the activist values that guide my every day.

The Great Wall was created for two global audiences, and because of that, it was a genius move. Chinese actress Jing Tian stars next to Damon, and audiences everywhere delight. Right?

There are so many things to parse, the obvious one being that a story set in ancient China does not need to star a white dude. Damon is not whitewashing a character in the traditional sense — as in, playing a role that was originally written for an Asian, a la Tilda Swinton — but it’s still giving the reins of a fantastical, Chinese story to a white Westerner.

And yet in some way, China’s enthusiastic response to Damon’s casting reminds me of being 12 and wanting white approval. It reminds me of thinking that a body with Eurocentric features would make me more valuable and loveable, and in that sense I reluctantly understand.

Put a white face on the poster for a movie starring a Chinese actress, by a Chinese director, and it becomes a vehicle for success and attention. One thing’s for sure: Identity is integral to the movies, and it runs deep.

Zoe Cheng is a sophomore majoring in writing for screen and television. Her column, “Wide Shot,” runs Wednesdays.