All the World’s a Screen: Martin Scorsese compels us to define ‘cinema’

When you don’t know how to start a piece of writing, you’ll find parallels to your argument in the most unlikely places, for there is nothing new under the sun.

“Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs” is one of my favorite movies. It’s quite simple, quite hilarious and quite insightful. A young scientist — Flint Lockwood (Bill Hader) — invents a machine that can turn water into food to save his starving small town. The trial run goes terribly, and the machine disappears into a cloud. A failure once again, Flint walks away dejected — until a slice of cheese falls on his head … and then some lettuce, tomato and a bun, until a whole storm of hamburgers pummels the town. Flint is a hero.

Before long, humanity kicks in: The populace floods Flint’s laboratory with orders specifically tailored to each person. Flint appeals to every single one, and the machine (as well as the people) become bloated with food — wild and dangerous.

Flint gives the people what they want, and it takes a whole movie for the customers to see how foolish they were to make such unhealthy demands.

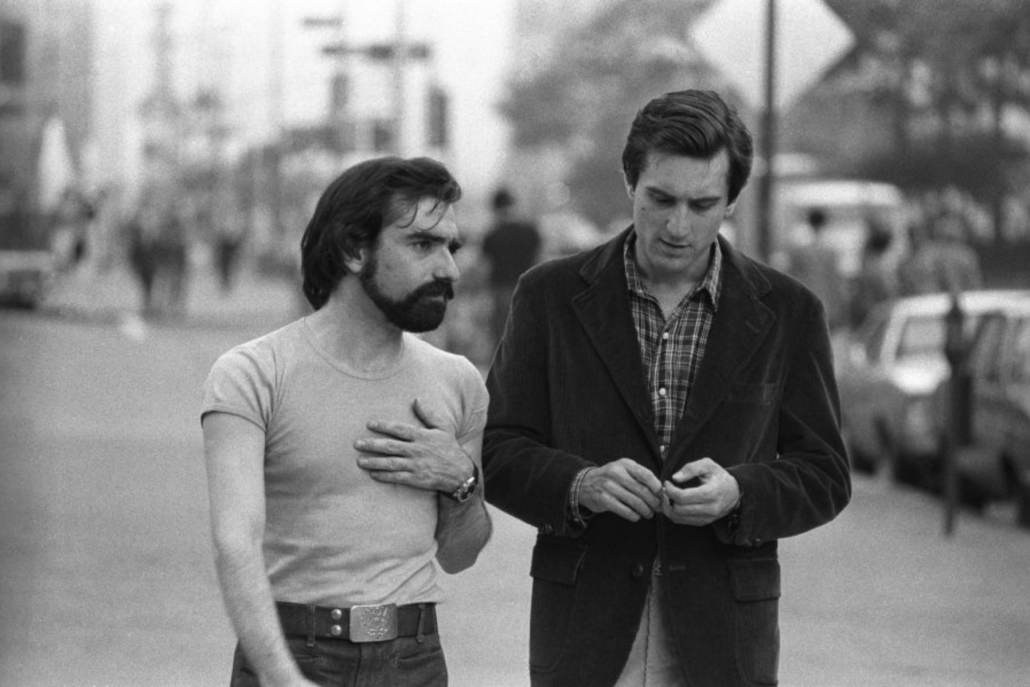

Last week, Martin Scorsese capitalized on his controversial statements regarding Marvel movies — that they were “not cinema,” as he told Empire Magazine. In an op-ed for The New York Times, Scorsese did not recoil but rather expanded on his thoughts regarding the kinds of movies big studios like Marvel put out.

“Many of the elements that define cinema as I know it are there in Marvel pictures,” Scorsese writes. “What’s not there is revelation, mystery or genuine emotional danger. Nothing is at risk. The pictures are made to satisfy a specific set of demands, and they are designed as variations on a finite number of themes.”

First, we love a guy who calls movies “pictures.” Second, I agree.

Scorsese makes the case that movies are an art form because they carry intense emotional impact, take risks, speak to our common humanity — and all this spouts from a single artist.

Richard Brody, writing for The New Yorker, writes that the idea supporting Scorsese’s argument is that of the “auteur.”

“‘Auteur’ [signifies] the idea of the director as an artist who, though self-evidently not the sole artist working on most movies, is more than a conductor or stage manager,” Brody writes.

A true auteur director is one who is so involved in the construction of the film that what he or she says goes, and the result is a film that accurately captures their worldview, not the expectations of studio executives or a bunch of fans.

Scorsese cites some of these kinds of artists working today as some of his favorites: Paul Thomas Anderson, Claire Denis, Kathryn Bigelow, Wes Anderson, Spike Lee. There’s a reason these names are famous: We know they are directors in the true sense of the word. Their names conjure images with a distinct look, stories with specific themes and feelings with universal wings.

So, the problem — and Brody argues this, too — is not the content of Marvel films but the Marvel of it all. As Scorsese says, there’s little to no risk involved in these movies. They are made primarily (not solely) to appeal to the audience, to tickle their senses — not to challenge them, not to force them to walk a mile in a character’s shoes, not to make them uncomfortable.

Such was the plight of Flint Lockwood. He created something beautiful that was quickly handed over to the whims of the masses. In their hands, the machine malfunctioned; it did not do what it was designed to do. When all your energy is concentrated on making people happy, you are not doing what you were designed to do.

Too deep? Let’s bring it back to the cute old man with glasses.

Scorsese has helped me understand movies better. I want to believe in a world where “cinema” is not pretentious for most people because everyone could use a little more empathy. And that’s what critic Roger Ebert called movies: “an empathy machine.”

If all we get is a diet of carefully tailored films, we won’t get uncomfortable, and we won’t grow. Art expresses humanity, and humans (shocker!) are very, very complicated. If we’re not willing to wrestle with the complicated, sometimes shocking portraits of Travis Bickle in “Taxi Driver,” of Guido Anselmi in “8 1/2,” of Mookie in “Do the Right Thing,” of the Kim family in the best movie of 2019 (yes) “Parasite,” then will we be willing to try and understand real-life people who are even more complex than these screen characters?

I hope you can see this isn’t about worshipping Scorsese. It’s not about abhorring superhero movies. It’s about you, me and our neighbor. We can be entertained by the cookie-cutter Marvel movies — for movies should also be entertainment, and Marvel makes some really good cookies — but we must not settle. Our own humanity may be at stake.