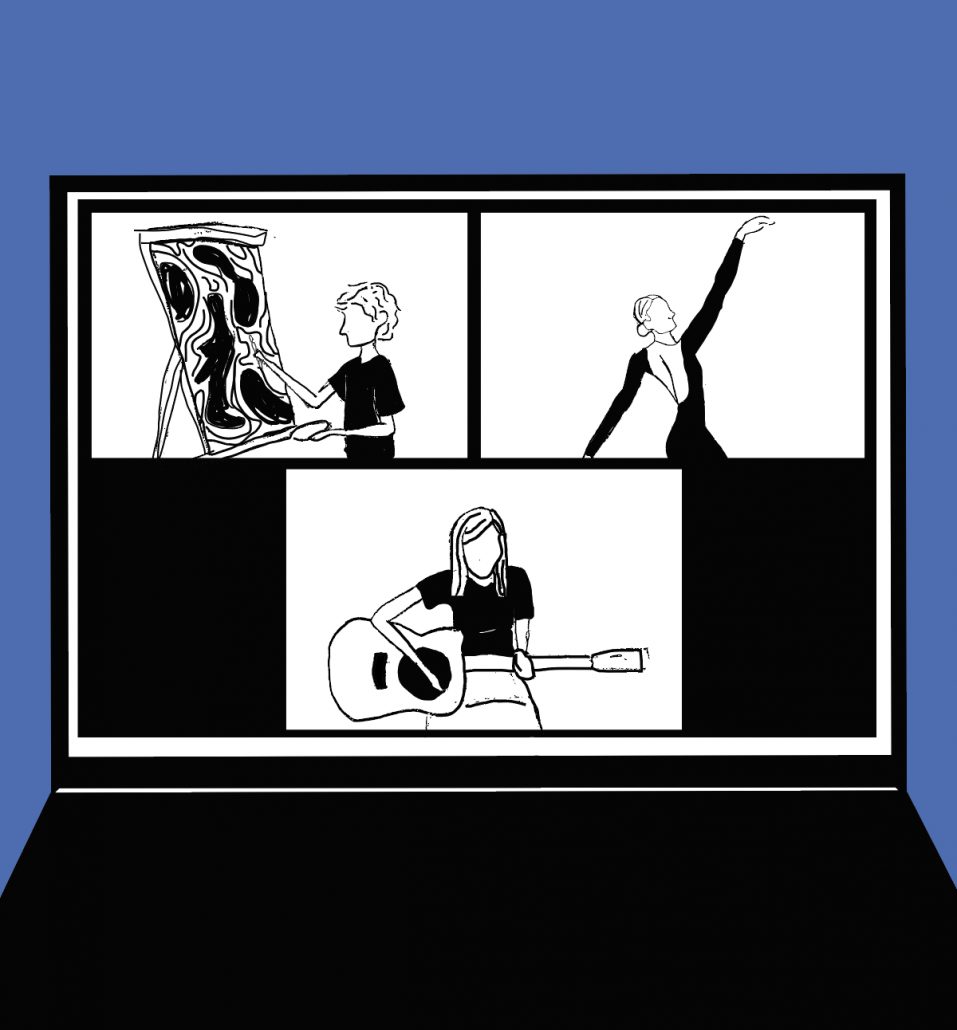

Got no feel, got no rhythm: How performance and art classes are adjusting to Zoom

Every morning at 9 a.m., sophomore dance major Davon Farmer attends his ballet class through Zoom. It starts the same as always — with an exercise at the barre, a stationary handrail used in ballet. Away from the resources provided by the Glorya Kaufman International Dance Center studios, Farmer practices with a chair instead.

Due to the coronavirus outbreak, Farmer’s professors instruct the ballet class through a blend of lecture and movement, and the session ends after reviewing several techniques. Then, Farmer is off to the rest of the day’s classes, which include a mix of hip-hop and contemporary dance, repertoire performance and improvisation classes all adjusted to the online space.

“For my improvisation class, we worked on gyrokinesis [exercise], which is a lot of sitting down because people were limited with space,” Farmer said. “We’ll also watch different performance pieces and then write a short summary on how we feel about them … we’ll have to look at different pieces of choreography for different artists and create our own movement based off of that.”

USC students have been attending classes online since March 23. While all students and faculty have been adjusting to online learning, those in performance-based classes are especially challenged in adapting curriculums which rely on physical collaboration and feedback.

“Depending on where you are, you cater what you do in class to the space that you have or where you live,” Farmer said. “So for me, I’ve had the luxury to have enough space to be able to barre and do center [floor combinations] and be able to participate in my hip-hop classes.”

Since Farmer and his peers are unable to experience real-time correction or access a real barre, full-length mirrors, spring floors or other features normally available at Kaufman, his classes have dedicated more time toward studying other choreographers instead.

Although all stage productions have been canceled for the semester, Rebecca Tabor, a junior majoring in theatre, said her professors and peers have found creative approaches to acting in the absence of physical interaction.

“A lot of people use the [virtual background] setting on Zoom comedically, but I was thinking because the scene takes place in a library, I can get creative and do a green screen of a big fancy library … and [my professor] really loved the idea,” Tabor said. “But at the same time, the limitations are it’s really hard to … genuinely emit emotion or action through the screen.”

Other challenges Tabor faces include performing stage directions during the Zoom class, because the scope of her “stage” is dependent on where she places her laptop to accurately show her whole body in her room.

Christian Lopez, a sophomore majoring in theatre, has seen changes in his acting and directing classes, including shifting assignments to self-recorded videos or changing the context of scene partners’ interactions. For example, Lopez and his classmates have tried to make remote learning work to their advantage by changing scenes so that the characters themselves communicate over Zoom or FaceTime.

“Our work is based on human interaction,” Lopez said. “I definitely don’t think this is going to inspire a new wave of online learning from theater classes in the future, but I think everyone’s getting creative and we’re all trying to work through it for now.”

While theatre students are still able to perform together in a limited capacity, Dominic Anzalone, a sophomore majoring in popular music performance with an emphasis in drum-set, said he and his peers were scared of how they’d be able to continue the semester over Zoom with time lags and varying audio quality.

“If you told me a couple months ago that we’d be going online, I would not believe you, especially as a performance major, that this is the only option right now,” Anzalone said. “But [popular music] faculty from the beginning were like, ‘How can we still make the rest of the semester effective?’ … I feel like now I’m working on things that will really help me grow as a musician, not only [as] a drummer.”

His “Popular Music Performance” class has been using the app Acapella. Users can record numerous soundtracks through video and post them in a collage that plays the clips simultaneously. Several instruments and vocal parts can be synchronized through the app, allowing Anzalone to create tracks and collaborate with people across the world.

Anzalone is also taking an “Aural Skills” class, which trains the ear to identify specific elements of music, such as pitch, intervals, chords and rhythm. This class is further complicated by technical difficulties over Zoom, but so far they’ve been able to adapt to them.

“It’s been interesting,” Anzalone said, laughing. “We’ve been making sure to ask a lot of questions [in class] and the first week was figuring out the gimmicks of trying to get quality audio through Zoom, and I think we got them out of the way … Even the ensembles are done over Zoom, which is pretty surprising.”

Francesca Boerio, a sophomore majoring in music with an emphasis in classical guitar and cognitive science, said although she has been trying to collaborate with peers over Zoom, she’s only able to rehearse her own part. Boerio takes individual instruction classes and is also a member of a guitar duo and a guitar orchestra. Despite her professor’s best efforts to pre-record videos of himself conducting and have students play along, they all play on mute and don’t know what other orchestra members are playing.

“My teacher is really trying and still having us do rehearsals,” Boerio said. “But honestly, I would rather spend my time just learning new pieces or getting pieces ready for the fall so that we can play longer or more intense pieces that we normally wouldn’t be able to play in a semester.”

In terms of grading, Boerio still has juries, final performances in front of a panel of faculty. These will be done over Zoom, while other parts of her grading will come from video recordings of solo performances. Even before the pandemic and the switch to online learning, students in her department have performed degree recitals over Zoom or Facebook Live.

Boerio also expressed her gratitude for her department’s efforts in sending out external microphones for students who don’t have their own. As a guitar player, she feels fortunate to play such a mobile instrument while other departments, such as percussion, are renting out and sending larger instruments to their students.

“My teachers have definitely done a very good job of trying to make this all work,” Boerio said. “A lot of other instruments … they don’t have marimbas or timpanis at home … Our faculty, our three teachers, are so accommodating and willing and really want us to still succeed from afar.”

Theodore Haber, a junior majoring in composition, is taking a violin ensemble class as well as a pottery wheel throwing class. For the violin ensemble, members have been recording snippets of themselves playing and sending them to each other. In response to the announcement of online learning for his ceramics class, Haber took matters into his own hands, literally.

“I actually have a wheel, so I can still make [ceramics] on the wheel, which is nice, but a luxury,” Haber said. “It’s harder to see the demos [that the professor creates] at different angles.”

Purchasing a wheel made sense for Haber, who frequently makes ceramics and whose mother has a kiln. Despite his efforts to replicate his class experience at home, Haber said attending class in person can’t be replaced.

“It’s harder to feel connected to your peers and teachers, and being constantly on your computer is not great for your brain,” he said. “So [the semester] is still strenuous.”

Shoshi Kanokohata, a lecturer for Haber’s ceramics course, has altered the class to make it as accessible as possible, despite the prerequisite tools and materials normally needed for the class.

“We don’t have a wheel, we don’t know if we can fire … so we needed to adjust the syllabus,” Kanokohata said. “Some of the changes are switching to hand-building … and put in more sculptural elements to the assignments … I personally like food, so I went straight to the kitchen when I thought about ceramics in the house.”

Commonly used ceramics tools include whisks, plastic spatulas and rolling pins. Inspired by the parallels between cooking and ceramics, Kanokohata uses bread and bread-shaping videos as a substitute for clay. To make the class more accessible for students unable to leave their homes and to accomodate for flour shortages, he also asks students to make models out of cardboard or paper.

Despite the challenges students and faculty are facing, Tabor, Anzalone and others are finding silver linings during this unprecedented time. Tabor had serious doubts about what students would gain from Zoom classes, but she said the creativity of the restructuring has made her more optimistic.

“As I’m going through it with my teachers, we start thinking more outside of the box and try to learn as we go,” she said. “I do feel that it will help me in the long run, because most of my acting [and auditions] will be behind a camera … Having this experience with Zoom, even if it’s a fraction of an experience, I’ll be able to think outside of the box.”

Although music students no longer have the opportunity to perform together, Anzalone thinks this new method of learning and the time spent at home has brought his peers closer together.

“Now that everyone’s not playing gigs, everyone’s been focusing on themselves and working to make themself a better musician,” he said. “A lot of us have been collaborating on different projects … I feel like the music community has been so strong throughout this whole process, everybody wanting to work together even though we can’t physically be together.”