Politics and Prose: Obama’s promised land remains a promise worth fighting for

There is something I must get out of the way before I begin this column — ‘Politics and Prose’ is not an original name. It is the name of a bookstore in Washington D.C. I have not been there, but I would very much like to go. By all accounts, it appears to be an incredible bookstore, and I am indebted to them for possessing the necessary genius to create such a brilliant name, but I digress.

I am writing this column because it often seems as if our national political discourse is increasingly void of nuance.

The 2020 election, and many of the events that preceded it, demonstrated the increasing desire of more and more Americans to engage with politics. By and large, this is an incredible thing, but it is not without its cons. Many students are already aware of the prevalence of virtue-signaling and performative wokeness, but I believe the issue here goes beyond that. I can only speak from my own personal experience, but it appears that in some circles, critical thinking has been replaced by infographics and thoughtful contemplation has been replaced by a devotion to buzzwords and slogans.

Infographics, buzzwords and slogans are not inherently bad. In fact, they often distill and distribute messages and ideals that can enlighten those who come across them. I want to make this clear: I generally like these three things. However, it should not be controversial to simply suggest that our seemingly increasing reliance on them to understand our shared political reality is concerning.

So that is why I decided to write about books. There is something that happens to you after spending a couple of days or weeks with a book that just can’t be mimicked by other mediums. Books also offer their writers a chance to explain themselves and argue their point without being confined to the limits of social media. Infographics and buzzwords might be effective communicators, but they simply cannot capture the necessary complexity that a book offers.

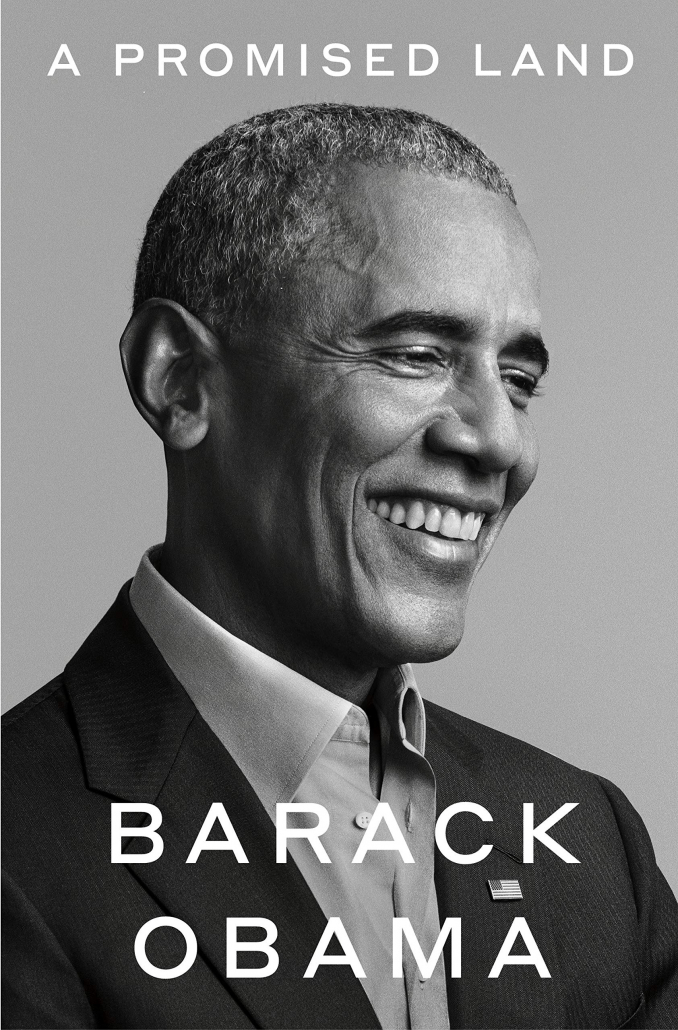

In that same vein, I’ll begin this column with Barack Obama’s “A Promised Land.”

Released Nov. 20, the memoir tells the story of Obama, in his own words, from some of his earliest childhood memories to his first two and a half years as president of the United States. The book has been received remarkably well since its release, and rightfully so; Obama’s prose is beautiful and his details are captivating. The former president is also strikingly introspective in his memoir, often inviting the reader to evaluate his ambition and his intentions, his shortcomings and his triumphs.

The memoir has also been praised for its ability to mean many things to many people. For some, it might serve as a commentary on U.S. race relations. Obama doesn’t shy away from discussing the topic of his racial otherness or some Americans’ aversion to it. For others, “A Promised Land” might read as an insightful look into the inner workings of the executive branch. Many might read it simply for its gossipy bits — who knew the President’s trips to his own bathroom were monitored by the Secret Service and referred to as trips to the “secondary hold?”

“A Promised Land” is all of those things and much more, but for me, it read primarily as an exposition on what it means to be American and what America is. The portrait Obama paints of the country, its public servants and its citizens is an inspiring one — one that evinces a patriotism rooted in compassion and tolerance.

This prevailing ethos is best expressed during Obama’s speech at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, a speech that Obama presents as one of the most significant, catalyzing events that catapulted him to national prominence.

“[…] There’s not a liberal America and a conservative America — there’s the United States of America,’ Obama said. “There’s not a Black America and white America and Latino America and Asian America; there’s the United States of America.”

This same patriotic current ebbs and flows through much of the book and does appear to sincerely inform much of Obama’ worldview. Still, for all of the pride in America the speech elicits, it also foists upon the reader a troubling question: Was the “magical” country Obama described really just a fantasy?

Any American with a modest understanding of our national state of affairs is surely able to see that America is anything but united — what with insurrectionists successfully invading the U.S. Capitol on the orders of former President Donald Trump, feckless Senators challenging the results of an election despite droves of evidence to the contrary and a sizable proportion of Americans willfully refusing to respect public health guidelines despite a death toll of nearly half a million Americans.

However, Obama’s memoir is not blind to this sorry, foul state of affairs. In fact, his memoir presages much of the political violence Americans see today. Obama recalls a white woman “grimly unwilling” to shake his hand and people sporting confederate flags outside of his campaign events, telling him to “go home.” He recalls the “nativist bile” that Sarah Palin spewed to her audiences, who in turn would shout “terrorist,” “kill him” and “off with his head” in reference to Obama.

Obama writes much, much more about the political rot he sees spreading across the country. Though he spends ample time extolling the decency of many Americans, ordinary citizens and public servants alike, and the hard, often heroic work of government officials on both sides of the aisle, one still cannot help but notice in his memoir a creeping, malevolent force gaining traction in America, like a spreading cancer one encounters every fiftieth page or so.

In light of this, it is clear that the America Obama described in 2004, the same America he describes throughout “A Promised Land,” is still, as the title suggests, a promise — a promise yet to be fulfilled, but still a promise worth fighting for.

Stuart Carson is a senior writing about political literature. His column ‘Politics and Prose’ runs every other Monday.