Out of fear through love: a review of ‘The Just and the Blind’

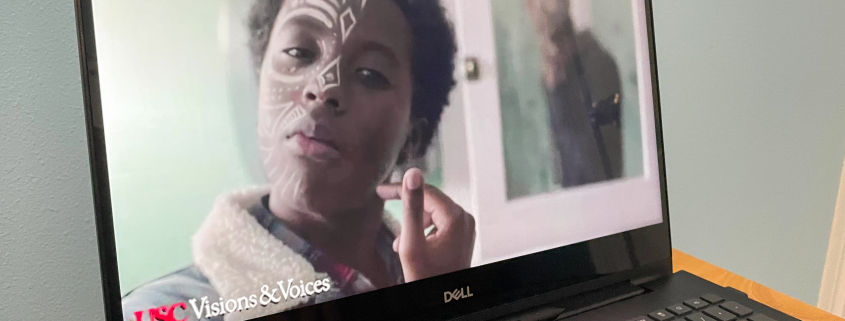

“Where do I fit if I cannot moan.” In “The Just and The Blind,” spoken word artist Marc Bamuthi Joseph explores the battle between fear and love through a tense dialogue between a Black father and son. The multimedia performance screened Tuesday through Visions and Voices and is in collaboration with musician and composer Daniel Bernard Roumain and flexing pioneer Drew Dollaz.

The show originally debuted in 2019 as a part of Carnegie Hall’s Create Justice Forum. Now, Joseph, Dollaz and Roumain perform in three separate locations, but the content only becomes stronger as the creators explore racial justice efforts in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

During an audience Q&A, Joseph revealed his spoken word poetry was the oldest component of the work. His poetry takes the audience through the journey of a Black father growing out of an age when he’s most vulnerable to injustice at the hands of the American legal system as his son enters that same age bracket. Roumain’s provides a chilling accompaniment, while Dollaz’s improvised movements imbue the piece with raw unexpected emotion, emphasizing the tragedy that is boyhood disrupted. Dollaz describes his preference for improvisation as “always revealing feelings [as they come] in the moment.”

Joseph’s poetry opens with a father’s anxious testimony. He describes afternoons outrunning doormen on the Upper East Side in a nostalgic tone making it clear these spats were simply a young boy’s innocent search for excitement: “Of all the genders, boys are the most stupid.”

The following short narrates a timeline of demonization: Age three is where “Black boy beauty probably peaks,” entrance into the public school system at age six – in Oakland this time – is where instructors “beat the drum out of him,” and during the teen years, “all signs of Black boy cute go away.” This narration outlines the emotional roadblocks imposed by the American legal system’s denial of Black boyhood.

This realization defines the tension between father and son. In the following piece, “17 Reasons Why I Smoke Weed,” the performance takes a comical turn in which Joseph champions the medical uses of marijuana; “I’ve seen it heal my family.” But he also admits to using marijuana to ease the “PTSD from just walking around in my Black body.”

Yet, in “Three Reasons Why My Son’s Car Should Not Smell like Weed,” he staunchly chastises his son caught in this same act. The sudden tonal shift mirrors the stakes surrounding the message he pleas for his child to understand: One legal reason to search can end his life.

“I instinctively assume that jail in Senegal sucks worse than jail in the states.” Joseph goes on to highlight the irony of perpetuating U.S. nationalism while being shunned by the country. It’s American identity the narrator calls on in an encounter with Senegalese police, but when this appeal doesn’t work, an already desperate identity crisis is only heightened. While the speaker doesn’t feel entirely American, he also realizes he wants to build a legacy in and lay claim to the country built on his ancestors’ backs.

Another double crisis is presented in a monologue dedicated to Ahmaud Arbery which Joseph shares he had not written until after the events of Arbery’s murder during the coronavirus pandemic. “Symptomatic said systemic violence sadistic bigots and a complicit network of badges and judges.” The addition of this piece provides a concise analysis of systemic racism. The unending and virus-like cycles of racist acts makes the father certain that racism is embedded in American society as he grows older. Instead of curing Americans, he calls the audience to set our sights on changing the system that allows perpetrators to use it for an outlet of their hate.

It’s easy to assume the American legal system is the target of the performance’s critique, but this focus is soon forgone in favor of exploring a more sinister fear: a learned fear of oneself. “Your dad thinks about crossing the street when he meets someone who looks just like you,” the father bemoans. In “Fear,” images of young men in constant conflict with one another overlay Joseph’s description of self-hate. After living life as a Boogey-man in the shadows of America, the narrator forgets his own image, developing a sinister sense of self-hatred that passes on for generations.

The performance closes with a painful exclamation, “Bury me in the struggle for freedom.” This struggle isn’t defined by interactions with white supremacists’ interests, but expressions of love to counter fear.

“In defiance of silence, we claim the right to love,” Joseph said while some assume making such weighty work can be fatiguing, this creative expression and collaboration is how he expresses love and heals from fear.

Make no mistake – “The Just and the Blind” is a heavy performance that doesn’t shy away from discussing all the tragedy that comes with the American carceral system. However, recognizing the cyclical and unending nature of racism, Joseph calls on Black men to prioritize healing through radical self-love.