Soft Power: Chinese girls dream of Chloé Zhao

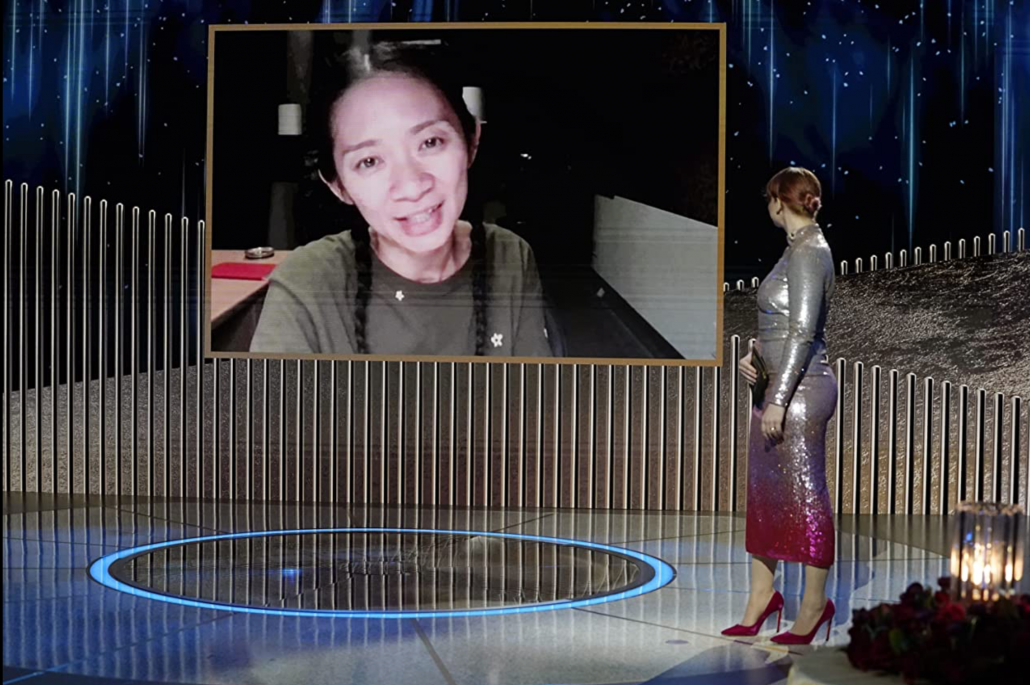

By the time this column comes out, it’ll have been a week since the Golden Globes, but I still want to talk about Chloé Zhao. Can we talk about how great she is? She, a Chinese woman, virtually entered a room and came out as Best Director. She broke records and made history.

“Nomadland” won Best Motion Picture, a testament to Zhao’s abilities as a director and writer. Chinese nationalists claimed her as the “pride of China” — yet, “Nomadland” was recently censored in mainland China for a comment Zhao made in 2013 that was allegedly “anti-China.” Asian Americans laud her victory as a win for Asian American representation in the United States.

Throughout all of this, her narrative will be politicized, as any discussion of a Chinese woman winning an acclaimed U.S. award will be.

This isn’t to say that it shouldn’t be. As a Chinese American, I do believe that Zhao occupies a unique intersection between China and the United States — something that Chinese Americans are no stranger to. On both Chinese and U.S. social media platforms, there is and will continue to be discourse about what her “success” means, the implications of her rich celebrity family background and most importantly, whether she’s a Chinese or U.S. storyteller.

Inevitably, there will be the recurring theme that Zhao living in the United States for so long has diminished her Chinese sensibility. There will be the idea that a film’s success can somehow represent one’s whole identity. There will be the idea that because her stories don’t explicitly factor in Chinese-ness, she has truly broken out of the box and become a universal storyteller.

All of this is to say, of course, that “universal” means stories about the human condition, which in that regard, “Nomadland” is. “Nomadland” is a beautiful story of what it means to be human and alone. It’s important to recognize, however, that some Chinese audiences don’t view it as a “universal” story. Shanghai-based film critic Xiao Fuqiu described it as a “pure U.S. story,” echoing the thoughts of other Chinese film experts.

I’m saying this because I’m wary about the idea of “universality.” I’m concerned that “universality” might mean Chinese storytellers being recognized for stories separate from Chinese-ness implies that they have decided to be less Chinese in favor of a “universal” identity. Maybe because to me, a story about Chinese people is just as much a story about the human condition.

Obviously, I’m no expert on politics (nor much of anything, for that matter). I’m just a Chinese American girl who wants to be creative and, similar to Zhao, tell stories about the human condition. So for purely selfish reasons, I want to think about Zhao not through matters of citizenship or who can truly “own” her success — I want to think about being Chinese as a matter of being creative and recognized as a Chinese person owning your own success.

Zhao has stated in an interview with Vulture that being Chinese was simply the context in which she existed as a Chinese person in China. She herself has said that she isn’t that interested in politics. This doesn’t necessarily mean, however, that she isn’t proud of being Chinese — being Chinese just felt normal to her. She felt freedom in not necessarily having to tell stories about being Chinese. There was a kind of merit to be found in distance.

Likewise, I think Chinese storytellers should be able to tell stories about whatever they’re passionate about, because there’s nuance in specificity. Whether the story is an “American Western” or about Chinese communities, I believe that Chinese people making art is in itself creativity that should be celebrated as any other.

I believe that it’s important to recognize and center Zhao’s own words in this. She wants to tell stories “bigger than her.” To me, it’s not so much about “transcending” identity as it is about centering yourself within the story and trusting yourself to do it right.

We can celebrate success while questioning ideals of universality. We can feel gratified that a Chinese woman, a woman of color, has become the first Asian woman to win Best Director. We can do all of that while questioning whether Chinese storytellers need to tell stories that aren’t about Chinese people in order to be internationally recognized.

We can also reflect: what does it mean when a Chinese filmmaker coming from China can tell such a “pure U.S. story,” and do it well?

A recent article in The New York Times about Zhao’s success is titled “Chloé Zhao becomes the first Asian woman to win the Golden Globe for best director.” At the very bottom, a correction reads: “An earlier version of this article mischaracterized Chloe Zhao as Asian-American. She’s Chinese.”

Yes, she is. She’s a Chinese storyteller who has gotten recognized for her storytelling — and for a Chinese girl like me, that’s the dream.

Valerie Wu is a sophomore writing about the arts and pop culture in relation to her Chinese American identity. Her column, “Soft Power,” runs every other Monday.