USC’s ‘zine scene’ gives artists a platform

When one envisions rebellion, they might picture rebels flinging Molotov cocktails at police cars and oppressive institutions engulfed in the flames as collective chants for justice permeate the air.

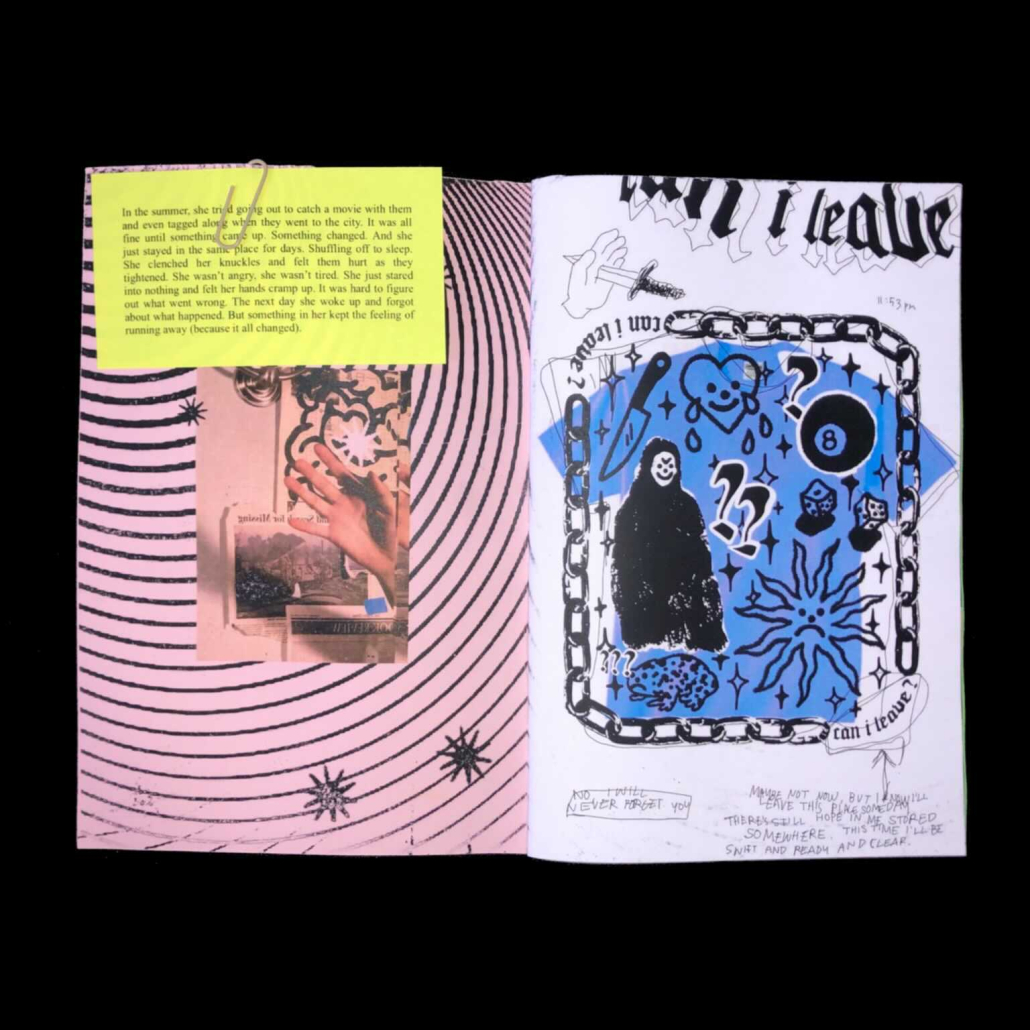

But Arielle Toney, a fifth-year senior majoring in art, envisions something a bit different. Her rebellion is a small handmade booklet, filled with confessional drawings and musings. It’s a medium that has been used by a breadth of creators — from punk rockers of the ’90s to radical activists and mutual aid orgs to even cartoonists and painters: the zine.

Her silent rebellion is steadily making noise among USC’s artistic community.

“At its core, the reason [zines have been getting popular] would be everyone needs an outlet, especially in these last few years that have just been storm on top of storm,” Toney said. “And social media has been getting increasingly polarized or censored or policed.”

Toney began crafting zines in Roski School of Art and Design professor Jennifer West’s “Riot Grrrl” zine class her sophomore year. It was in that class that she learned about how the riot grrrl movement — a movement in the 1990s focused on making safe spaces for women, femmes and queer people in punk — used handmade booklets filled with manifestos to mobilize the marginalized.

It’s through this ethos of bringing power and platform to unheard minorities that she drew her first zine, “Bunny Brain.” In the zine, Toney uses seemingly “juvenile” visual motifs, such as hearts, the color pink and doodles, to investigate her complex relationship with femininity as a Black woman coming from a majority white school in Texas.

At the end of the zine, Toney poses a question: “Is this too straightforward for your gallery? Which keeps this from being art, my voice or the hearts?”

Like Toney’s pervasive question, Dawn Stahura, a zine librarian and expert at Broward College in Fort Lauderdale, explains that zines exist as a means to reject mainstream notions of validity and importance. They challenge the spaces that marginalized communities have historically been shut out from, like the publishing industry.

“Speaking from an [LGBTQ+] community perspective, I think, in general, zines and comics and stuff … They’re so much less policed than if you wanted to make, like a full-fledged animated show, or, even if you wanted to publish it into a book, you can easily self-publish this sort of stuff on your own,” Toney said. “You don’t need anyone’s permission, and you don’t need to change anything to fit an industry standard. It’s just all you on the page.”

It’s this ability to be personal and confessional through these small, cheap inkjet booklets printed on copy paper that Zoe Alameda, a junior majoring in fine arts, finds liberating.

“It’s nice because people know you made it, but, because it’s in a book and not your [Instagram] profile, it’s like disconnected in a weird way, which is nice because you get to reveal more. I find myself revealing more about myself in these zines rather than posting on my story how I feel,” Alameda said. “Which is very cathartic because you can do it in a form of art rather than just as a written vent post.”

Alameda’s work consists of eclectic artistic perzines (or personal zines) filled with collected and hoarded imagery that is compiled, shredded and manipulated. She sometimes will write directly on a copy and even add found objects such as crumbled receipts.

From memes to non sequitur “cursed imagery,” Alameda’s disjointed, discordant composition of images mimic Gen Z’s convoluted relationship between digital and physical realities, zines filled with fragmented scraps that reflect Gen Z’s chaotic media consumption.

Alameda began making comic books in high school, which led them to learn about zine fests — festivals where zinesters and small artists sell their self-published work. Once they learned about this thriving community in Southern California, they began crafting and selling zines.

Alameda enjoys the freedom of zines as well as their accessibility.

“Back to that notion of like ‘Zines can be for anybody, made by anybody,’ you don’t have to be a big person to or have a lot of money to make these things. It’s something that you can just DIY and have out and publish.” Alameda said. “[The zine community] just adds to people getting to see each other’s stuff without [being] like, ‘Oh, this is so high standard, like no one’s allowed to touch it except for these people.’ Anybody can access it, which is really great.”

The amorphous definition of what a zine can be and who can access it allows Nicholas Forman, a freshman majoring in media arts and practices, to use the medium as a space for experimentation and spontaneous creative bursts.

“ [I’m] always using it as some sort of little exploration, like a little learning process and trying to find something new in myself through [making zines],” Forman said.

His zines are filled with vibrant, hazy scraps of collage, drawings and heavily digitally manipulated photos and media. One of his zines, “a scroll zine,” is a mini one-page booklet that features cacophonous, gritty-edited screenshots of Forman’s screen-recordings that show him scrolling through Instagram.

For Forman and many other zinesters on campus, the physicality of zines provide a way to bring ideas to the forefront in a more concrete manner, especially with the transient nature of social media.

“[A zine] is not just something you can scroll past, it’s something that you should read and you should look at,” Forman said. “And so I think it was kind of almost this, a little bit of this obligation created when someone’s giving you this piece of paper thing, and you’re like, ‘I guess I should look at it.’”

Zines are mediums where creators can place themselves at the forefront of conversations that might never be facilitated on a college campus.

Stahura explains how zine creators can, in a sense, become the experts and facilitators of their own experiences through this handcrafted medium.

“So many students feel a complete disconnect between the lives that they lead, the communities that they live in, how they identify and the shit they’re learning in college,” Stahura said. “We have a hard time with certain groups feeling like they even belong on campus or … higher ed institutions. And I think that zines are that one space where you can create a sense of belonging. ”

It’s this sense of belonging that Toney felt through her “Bunny Brain” zine after sharing it in class and receiving support from her classmates. It’s through this same desire for community that she founded the Visual Narrative Society, a club that creates space and time for students to work on their narrative artwork such as zines, comics and animations.

VNS will host a comic book fair in the Lindhurst Gallery Dec. 7, which will highlight students’ self-published and self-printed zines and comics. The event will serve as a space to bring student’s self-published artwork into the forefront of the greater USC community.

“But my hope for the club [is to] provide a regular meeting space to create work and show work with your peers that isn’t necessarily for a grade,” Toney said.

Stahura believes the creation of a platform for zines — whether through a comic fair or even through the acknowledgement of zines through a school’s library (where USC Special Collections have collected student zines in Doheny Memorial Library) — is transformative for students who may feel like they don’t have a place in the greater college campus.

“[Having a zine collection on campus] means, for every zine that enters the zine collection, the institution, you are literally changing the landscape of a library’s collection,” Stahura said. “There are now going to be stories that are going to be able to be heard, that are written not only by students, but I can guarantee you by groups that have very low visibility in mainstream media and in the scholarship… That’s powerful.”