Project memorializes Armenian American stories

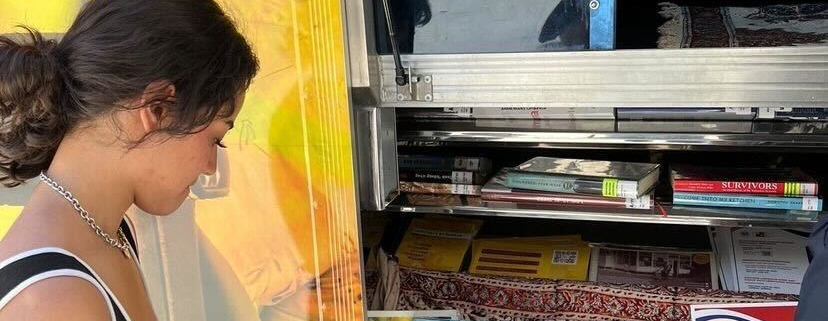

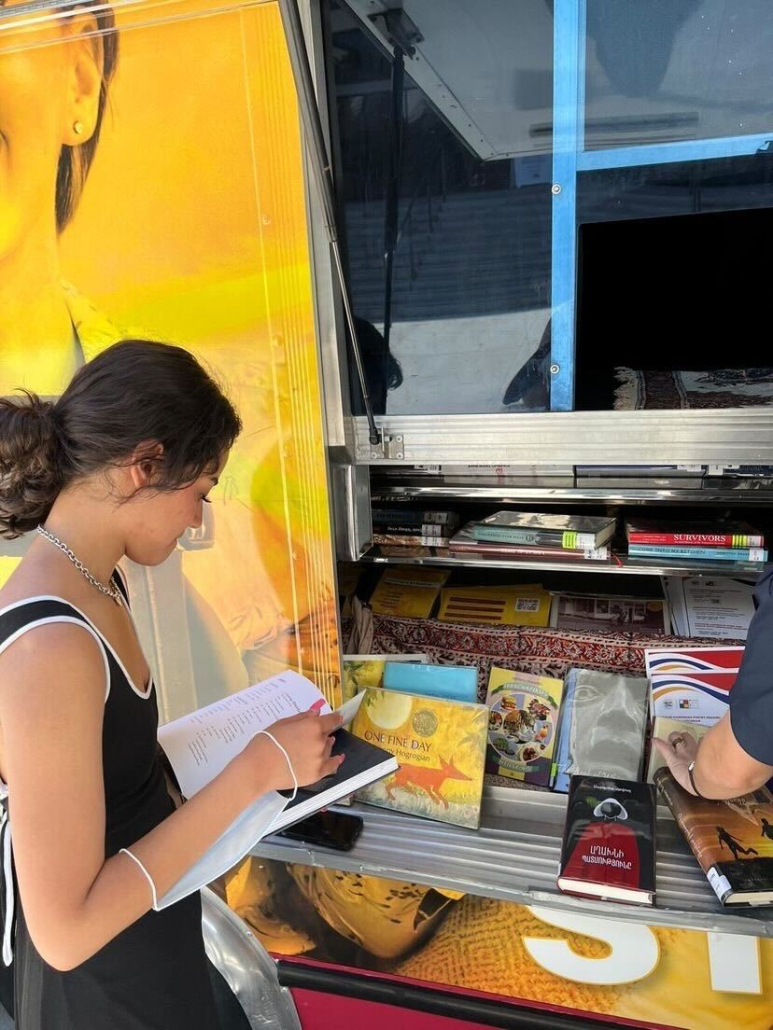

Speeding down the streets of Los Angeles since the beginning of April — known to some as Armenian History Month — a lively, gold-colored food truck makes stops at community centers, high schools, businesses and churches. Its purpose, however, is not to serve meals but to collect stories.

Memories from the Armenian diaspora, ranging from recollections of the Lebanese Civil War, stories of independence from the Soviet Union and the dating lives of Armenian young adults, have found their way into this truck-turned-mobile-studio as part of an oral history project known as #MyArmenianStory.

Traveling around various areas in Southern California — home to almost 500,000 Armenian Americans — the project welcomes all to share their life stories and experiences. Set to be housed in the USC digital archive and in global collections, the collected records will look to serve as a primary source for research use.

The idea for oral history interviews began four years ago within the USC Institute of Armenian Studies. Historians previously conducted interviews with camera crews inside residents’ homes around L.A. and contemplated branching out to different parts of the state and country.

The house visits halted in 2020 because of the start of the pandemic, but the pause gave the project new direction, said Gegham Mughnetsyan, a leading archivist in the USC Armenian Institute and a key figure in the project. When virtual interviews began, institute members thought of making the oral histories more accessible and available for people. The converted food truck became the newest vessel for the project, representing by design the fact that many Armenian Americans in the ’60s had their start in entrepreneurship by opening food truck businesses.

Mughnetsyan said there is a unique power in listening to oral histories from individuals compared to typical documents and manuscripts. He also noticed that, when interviewees tell their unique life stories, it often brings up memories that they haven’t thought about in years.

“There is only one storyline in [a document], and it does not evolve,” Mughnetsyan said. “But when you are collecting oral histories through questions you asked, sometimes it brings up completely different tangents that people themselves didn’t think were important to mention, but turn out to be very crucial.”

Mané Berikyan, a student worker on the project who helped conduct interviews, noticed interviewees answered questions in a wide variety of ways, with some viewing the project as a way to preserve family histories and some answering the questions more casually.

“I’ve had friends talk about their dating lives and people talk about their great great grandparents genocide survival story,” said Berikyan, a freshman majoring in international relations. “That also enriches the archive that we’re building and it’s going to give us a very wide variety of material to choose from in the future.”

Christine Almadjian, a junior majoring in law, history, and culture, said that prior to the #MyArmenianStory project, many of the stories surrounding Armenian identity she had heard focused on the deep wounds within the community, stemming from the 1915 Ottoman Empire genocide that caused the diaspora. Almadjian, who was invited to join the project August 2021, said the project has allowed her to hear joyful and empowering tales from her community.

“As a people, I feel like we’ve just experienced so much pain and so much suffering, and I feel like that’s at the forefront of a lot of the stories that we’ve heard in the past,’’ Almadjian said. “That generational trauma has embedded itself within each individual, regardless of status, but I feel like the stories have been able to be something of light and of positivity.”

According to Mughnetsyan, the project has also gained interest from other Armenian communities in the Central Valley, and the mobile studio may continue to operate into the month of May.

“Even if it doesn’t continue directly into May, then it will definitely be returning for a similar mission, because there is now growing interest from other places too,” Mughnetsyan said.