“Poster Girl”: An incomplete allegory

It might not take much effort to remember the dystopian renaissance that occurred circa 2010s, during which Veronica Roth’s “Divergent” joined “The Hunger Games” and “The Maze Runner” in redefining the young adult literary landscape. In Roth’s latest novel, “Poster Girl,” she poses the question of what happens after a dystopian regime collapses.

Having been the “Poster Girl” and “a symbol of the Delegation,” Sonya Kantor is banished to the Aperture, a dilapidated, prison-like complex for fellow loyalists to the previous government. Kantor lost her family, friends and betrothed during the uprising that led to the Triumvirate and exists in a state of perpetual longing for the near past. During the days of the Delegation, technology was limitless and the Insight, a device embedded in the eye from birth, gamified life through credits known as DesCoin. In the present, the blue circle around Kantor’s eye, rendered useless after its deactivation, serves merely as a reminder of all she has lost.

Kantor’s battle with the past and present is made more apparent through Roth’s worldbuilding by separating the Aperture as a place with Insights, tattered clothing, rats scurrying across the concrete and walls etched with the names of lost loved ones. After Kantor is recruited to solve the mystery of a girl taken from her family by the Delegation in exchange for her freedom, Roth introduces the world of the Triumvirate, which looks eerily like our own.

In the outside world, Kantor stands out as people gawk at her Insight and squint at her familiar face, one that used to be plastered on every wall with the slogan, “What’s right is right.” The Triumvirate has traded in the Insight for the Elicit, a glowing, handheld device that bears a stark resemblance to a phone. The trading of technology, one name for another, begs the question of whether they are all the same, inherently controlling and invasive, which brings the Triumvirate’s antagonist, The Analog Army, to the forefront of the story. They argue that the desire to “sacrifice autonomy and privacy for convenience” will be the population’s downfall.

Though the plot of “Poster Girl” is driven forward by the mystery of Grace Ward’s whereabouts. Kantor’s existence between two worlds is the most compelling aspect of the novel. Her perspective of the Delegation, the Triumvirate and her place in the world shifts as monumental events occur throughout the story. Kantor’s journey to finally unlearn the person she was during the Delegation, while also taking responsibility for her actions, makes her a protagonist worth exploring even further. Though the novel closes on a seemingly conclusive note, its anticlimactic ending can be traced to the unfinished development of Kantor’s character, an incomplete examination of the Triumvirate and the Delegation, as well as a romantic subplot that is left up in the air.

The Delegation is described through Kantor’s memories and exists in remnants within the ashes of the Aperture. As a result, the past world can be visualized, but only within the context of Kantor and her experiences. This incomplete image makes it difficult to differentiate between the ideologies of the new world founded by the Triumvirate. Both regimes value technology, albeit in different ways. However, there is not enough information about the Triumvirate to truly decide whether or not it is better or worse than the Delegation.

It is possible that the lack of details is meant to demonstrate the slippery slope of technology and the government, but the novel, running only 288 pages long, is wounded by the omission of clarity pertaining to the Triumvirate. Questions about the motivations of the government overtake the weight of Kantor’s mission, as well as overshadow her characterization. Though Kantor makes for an interesting protagonist, her identity is inherently tethered to both the Delegation and the Triumvirate. By not expanding upon the intricacies of these regimes, a disservice is done to the development of her complexity as a character.

The inability to fully understand Kantor makes it difficult to sympathize with the romance between her and Alexander Price. The addition of romance was surely meant to add another layer of intrigue to the story, but instead falls flat, not only because of Kantor’s flawed characterization, but also because of her partner’s imperfection in that department as well. It is ironic then that, despite Kantor’s character being insufficiently expanded upon, she remains the most complex character in the entirety of the novel.

The premise of “Poster Girl” promises an allegory of our world, a cautionary tale about technology and a mystery that is compelling from start to finish. It succeeds in professing the dangers of the modern world but at the same time, fails to create a memorable story as a result of a cast of characters that struggle to take command of the narrative. The worldbuilding establishes lovely visuals, but beyond that, the novel struggles to elaborate upon the past and present in order to elevate the events and dramatics of the story.

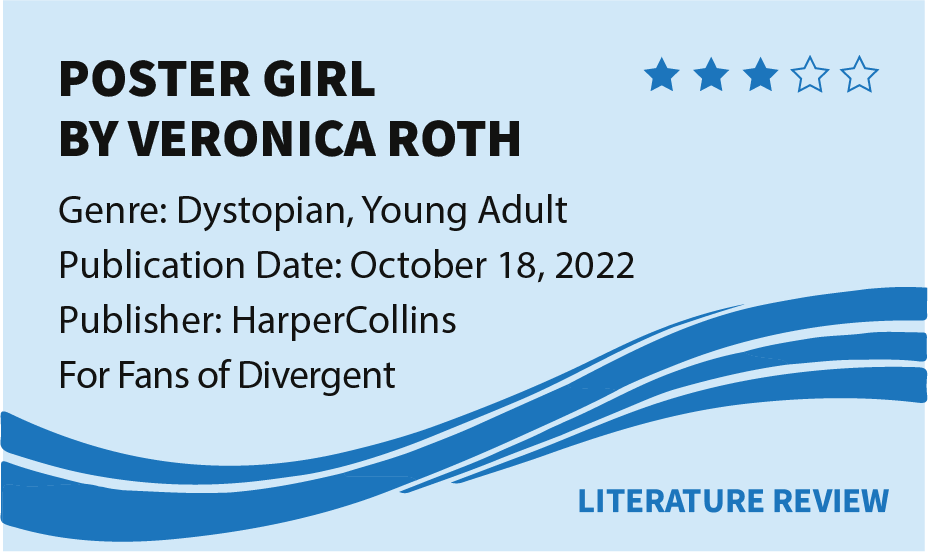

“Poster Girl” is an enjoyable, short read, but lacks the depth that many might be yearning for. The novel comes to a neat close, but questions that should have been answered throughout the story remain long after the book has been shelved away. But, it doesn’t seem as if “Poster Girl” was meant to end on a cliffhanger, but rather as if the story was deemed complete — even as the loose ends are blaringly apparent. As a novel, “Poster Girl” has potential, but its gaps and shortcomings make it to be a three-star read.