Long hours, unreliable resources, financial strains: ‘No choice’ for Architecture students

On paper, the School of Architecture is a “dynamic platform for educating and inspiring citizen architects” via “a foundation of rigorous research and inspired design” that has a century-long legacy of pushing “beyond the traditional boundaries of the field.”

But a growing disillusionment is challenging this narrative, as some students — surveyed and interviewed by the Daily Trojan over the past two months — said excessive workloads, financial burden and volatile communication with faculty and staff are fostering a stressful environment in the program.

Survey

The Daily Trojan surveyed students in the School of Architecture beginning Feb. 20 about their experiences in the program. Forty-four students responded: twenty-two in their first year, nine in their second and 13 in their third.

Respondents were first prompted to rate the quality of communication in the program on a scale of one to 10. Communication between faculty and students averaged at 4.6, while perceived inter-faculty communication earned a 4.25. For both, the most common rating was a 3.

Instructors

The survey also asked students to quantify how helpful or understanding their professors are when problems arise. To the former, 64% of students said “sometimes,” compared to 27% and 9% who said “yes” and “no” respectively. To the latter, 73% said “sometimes,” 21% “yes” and 7% “no.”

Students interviewed by the Daily Trojan after filling out the survey elaborated on the survey data and said that the quality of instructors varies significantly.

“How your semester goes really depends on who your professor is,” said Laura Pisciotte, a second year majoring in architecture.

Pisciotte said her professors have been sympathetic when it comes to illnesses that affect her ability to work.

“Second semester last year, I got [coronavirus] halfway through the project,” Pisciotte said, “and [my professor] was understanding that I couldn’t do as much work [and] that I couldn’t be present.”

Manuel Bernardino Jr., a third-year student in the program, recalled particularly negative experiences with professors.

“I’ve had professors almost question who you are as a person, your ethics, what you’re doing with your time as if it’s their business in the first place,” Bernardino said. “I played sports my whole life. I get how a football coach might be [harsh]. But I don’t need my professor to be a football coach. I need my professor to guide me in the right direction and help me when I need it.”

Lucas Brown, a first year in the architecture program, said he confirmed in a meeting with Associate Professor and Undergraduate Programs Director Doris Sung that the only degree requirement to teach architecture is either a bachelor’s degree or a doctorate in architecture — meaning that no formal training in education is required by the National Architecture Accrediting Board to become an instructor. As a result teachers often have little to no actual teaching experience when entering academia.

Brown said that as a result there was “an inconsistency with the performance of each of the instructors” because of these requirements set to teach in the program. He said that while he personally was happy with his studio instructor last semester, there are others in the program who are not nearly as satisfying.

“We have other instructors, this semester and last semester, who just are unable to communicate,” Brown said. “Even if they have the proper knowledge, they just can’t communicate it in an educational format.“It then becomes a dice roll of who’s going to be a good instructor and who’s not.”

Financial strains

Students are asked to pay for the materials, such as glue and chipboard, and fabrication tools, such as laser cutting or 3D printing, they use to create their physical models, as well as the programs used to complete digital assignments, such as the Adobe Suite, which other schools such as Annenberg offer at no additional cost.

“It was almost an expectation that we’d have to pay to use a 3D printer and laser cutting materials and tools that the school has,” said Jah-Mier’e Shelton, a first-year majoring in architecture.

The financial burden of the program is a common problem for architecture students. Roxanne Natal, a first-year in the program, said that while she has managed to avoid paying too much for model materials, she still wishes the issue were not so severe.

“I would consider myself a low income student, so I always try to spend the least money I can on materials,” Natal said. “But, I don’t think, in the future, [doing that] would be the wisest choice … Inevitably, I’m probably going to have to suffer a little bit.”

Funding for the School of Architecture was a particular issue raised by Bernardino, who spoke about how the costs of the architecture program are a significant burden on top of his expected cost of attendance. Still, he said he experiences doubt about what exactly students’ tuition is paying for within the program.

“I pay gas every three days to get here, then on top of that, I’m expected to spend close to $500 to $1,000 on models or pieces that, again, you spend so much time making,” Bernardino said. “Then [instructors will] just break it apart to help you see certain aspects of the project that you might not have seen.”

Bernardino said that he often wonders how much of his tuition is spent by the University on the program, specifically citing the plain construction of the architecture building — “It’s depressing, it’s just a concrete block,” Bernardino said — and printers and fabrication machines that often break.

“[It’s] ridiculous, for a school that charges this much money, that they don’t have their own supplies here available to the students,” he said. “If I knew my $70,000 would be going towards more innovative and inspiring spaces for everybody — not even just for me, but for future architecture students — hell yeah, go for it.”

In a statement Wednesday to the Daily Trojan, the School of Architecture wrote that while it is unable to discern the amount of funding it receives from the University — as USC’s annual financial report “does not provide breakdowns of individual school budgets” — it nonetheless “has the support of the university to provide the resources needed to serve our students, faculty and staff.”

Workload and mental health

Survey respondents also had the opportunity to rate their workload in the program. On a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 was “way too light” and 5 was “way too heavy,” the average was a 4; 52% answered with this number and an additional 32% rated the workload a 5.

In additional questions, 52.3% of respondents said that they were pushed to learn new materials and softwares at an unfair pace. Nearly 80% of respondents admitted to having ignored an illness to attend a class, and 77% said that they did so to complete a project.

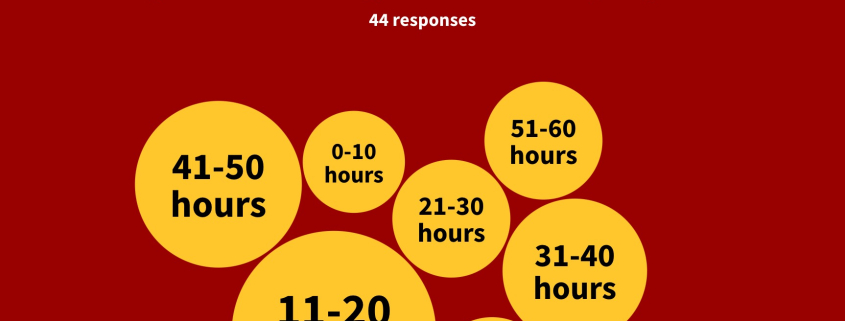

Outside of class time, those surveyed said they continue to work long hours on architecture assignments, spending anywhere between two to 15 hours each day working on studio projects. Some said that they have occasionally spent longer than two consecutive days working on a project with no sleep, with one respondent saying that they once spent 96 continuous hours — or four straight days — on a project.

Just over 60% of survey respondents said that the program had negatively impacted their mental health. About 16% percent said that it had not, and an additional 22.7% said that they were unsure.

Bernardino said the program has affected his mental health in ways that he had never experienced beforehand.

“I’ve always been a very confident person in everything that I’ve done,” Bernardino said. “Sports, fashion, anything … until I came here, and [the program] destroys me all the time. I have so many second guesses about myself, who I am. Why am I here?”

Just over half of the respondents said that they had at one point considered dropping out of the program. Those respondents’ reasons for not dropping out ranged from not having other majors that they would be interested in to telling themselves that the program’s stress was worthwhile.

For some, the program becomes too much to bear. Karsyn Wendler, a junior majoring in civil engineering, said she switched her major from architecture to civil engineering this semester because the program was taking too great of a toll on her mental health.

“It was getting to a point with [the] studio [class] where I was so stressed out about it that, if it meant sacrificing extra sleep or a meal, I would if it meant I could sit at studio to work for another hour,” she said.

Administration within the program has done little to change or listen to students, some students said. Bernardino told the Daily Trojan that Sung had spoken to students in his year and said that she never had to pull an all-nighter to complete work while studying architecture at Princeton and Columbia.

About 86% of survey respondents said that they have pulled at least one all-nighter to complete a project, with some noting that they have done so anywhere between five and 50 times.

Bernardino recounted having to drive home from the studio at 4 a.m. and almost falling asleep behind the wheel — “the scariest thing [he’s] ever experienced.”

In another conversation that Wendler said her cohort had with Sung, administration reportedly brushed off student stress as a consequence of needing to meet NAAB requirements. Sung did not respond to requests to verify such a conversation had taken place.

“[In] spring of last year, we had a conversation with [Sung] about the workload and the stress it was putting on us,” Wendler said. “The faculty’s response was, ‘Well, we have to meet these requirements for NAAB … there’s no choice.’”

The Daily Trojan reached out to Sung for comment on the allegations that she seemed to ignore student concerns and push blame for the program’s demands to the NAAB’s constraints. The Daily Trojan also asked Sung to comment on the survey’s data points that indicated students were suffering from stress.

“USC School of Architecture cares deeply about its students’ education, health and experiences,” wrote Sung in a statement Wednesday. “We want all our students to not only succeed but to thrive as they adapt to this unique education at a nationally ranked Architecture program. We are committed to listening to their concerns along the way and directly improving their experiences.”

Sung mentioned a continuing initiative called “Coffee Chats,” which aims to put younger students in contact with older ones. She also encouraged students to speak up to staff and faculty when problems arise.

“This current semester, a cohort of students have highlighted certain challenges,” the statement continued. “We held listening sessions, convened forums, prepared surveys and pledge to continue to keep these lines of communication open. We hear our students and strive to provide equitable access to resources that support them.”

Solutions

A student majoring in architecture, who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation from peers, said that the best way to create change was for students themselves to speak out.

“When we band together as a class, when we use our student voice and our perspectives, a lot can happen and a lot can change,” the student said. “That has happened in the past and it’s happening now.”

Pisciotte said that because she and her classmates spoke up to their professors last year, the program improved for them tremendously.

“This year has been so much better,” she said. “Our midterms don’t overlap anymore [and] our finals don’t overlap anymore.”

Students interviewed said that communication and openness from instructors was an area in need of improvement.

“It’s not supposed to be this weird, strict boundary between instructor and student,” Brown said. “The best thing that students and instructors can do is to just learn how to be more communicative with each other, not just between faculty and students, [but also] between faculty and faculty, just being able to be more clear of the expectations … so kids can pass while at the same time not risking their own mental and physical health.”

Natal said that a major problem that has stemmed from this communication issue is project planning, and that ideally instructors would learn from any mistakes made this semester and improve their planning strategies in the future.

Students also discussed potential systemic changes: Brown said that hopefully the hiring of a new permanent dean for the School of Architecture — which is currently overseen by interim dean Willow Bay, concurrently the dean of the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism — would enable some decisions to be made surrounding the school’s funding. Another such fixable issue, he said, would be a new grading system — such as “some kind of pass/fail system or a ‘B or above’-type grading system” — to take pressure off of students.

“If the teachers aren’t gonna be able to communicate it then at least the grading system will define the fact that it is okay to not always do well, and if you don’t do well, that’s fine.” Brown said. “As long as you learn from the mistakes then it’s okay.”

Justin Kaczender, a third year and president of the undergraduate student council at the School of Architecture, noted that since the architecture school’s curriculum is based on the NAAB accreditation, there isn’t much that can be immediately fixed. He said that a more immediate solution would be for the University to deal with the program’s funding.

“All of our requirements as [architecture] students are based on the NAAB board, which is who gives the accreditation out so that we can get licensed after school,” Kaczender said. “A lot of the issues within our school are more related to access to materials and the proper facilities to do the work that we’re required to do.”

Kaczender emphasized that a lot of responsibility for fixing these issues actually lies on USC as a whole.

“Our tuition isn’t necessarily going directly to the School of Architecture. It’s going to the school as a whole,” Kaczender said. “It would be nice to just try to urge the school to help [with funding].”

Those who have remained in the program, such as Bernardino, hope they will find that the experience was worth the strife it caused.

“[My parents would say] ‘Everything hard in life is worth pushing through. Just stick through it, it’ll be worth it in the end.’” Bernardino said. “I guess we’ll see after my fifth year if it really was or not.”