Non-Stop K-Pop: K-Pop and U.S. release frequencies just aren’t the same

Being a K-pop fan is simply better than being a fan of United States music culture. There, I said it.

This conversation began when I was talking to my boyfriend about ENHYPEN’s recent album release, “DARK BLOOD,” and I mentioned how the group hadn’t released any major Korean pieces since last summer. In K-pop time, this is a long, long period for a musical dry spell. Ten months between releases feels like an eternity.

My genuine surprise at ENHYPEN’s release delay stunned my boyfriend. This is because for U.S. artists (only speaking on behalf of the musical culture that I’m familiar with, but I’m sure artists in other parts of the world behave similarly), it’s normal for artists to stay dormant for years. Perhaps, I’ve become a little too accustomed to K-pop timeframes.

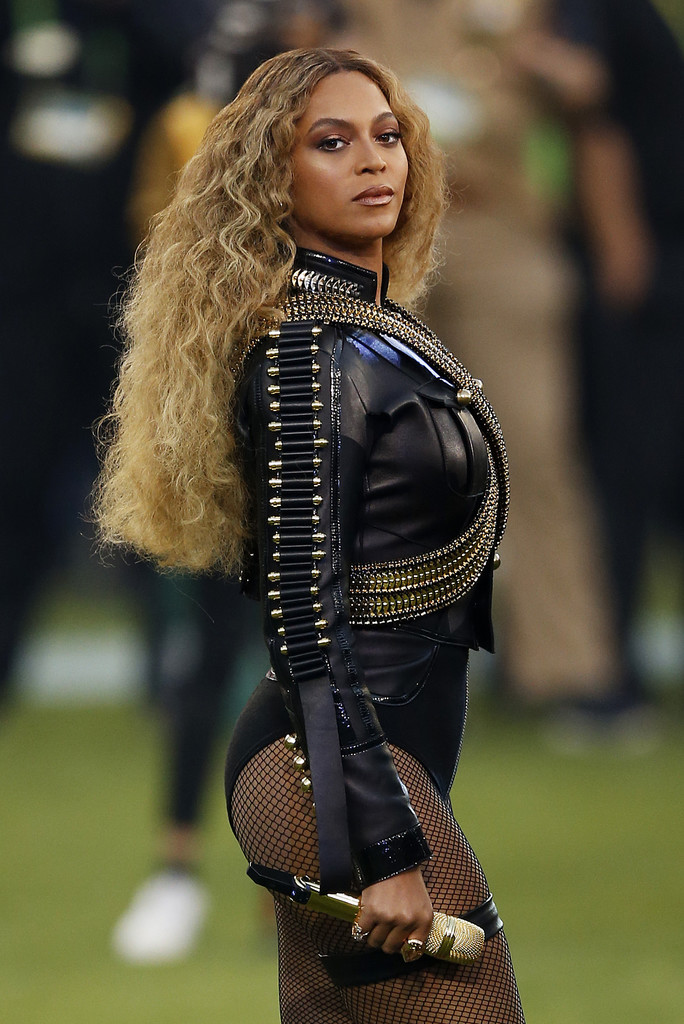

Take one of the most popular Western musicians: Beyoncé. Queen Bee’s “Renaissance,” which dropped in 2022, came after a three-year drought. Similarly, Eminem, who was crowned the “King of Hip-Hop” by Rolling Stone, only released three albums in a seven-year span between 2010 and 2017. And he’s still regarded as one of the best in his genre.

Although Queen Bee and Slim Shady’s discographies are objectively amazing, this would just not fly in the K-pop realm. BLACKPINK is one of the few groups to have a long hiatus that didn’t affect its popularity. The group went silent from October 2020 to September 2022, an aspect that was not received well by fans and was likely only possible due to its already solid global popularity. However, it’s still a point of contention between fans to this day.

This isn’t meant to belittle or bash Beyoncé or Eminem — their record sales speak for themselves — it’s just meant to serve as a comparative point.

According to most fans and K-pop websites, popular K-pop groups will have at least one comeback a year, but this usually becomes two or three, especially if there are holiday-themed releases like Stray Kids’ “Christmas EveL.” From my experience, this usually entails at least one mini album, and either another mini album or an astounding single EP. It is pretty rare for a group to release a full album — that is, an album with at least eight songs or so — and the ones that are released usually contain repackages or revamped versions of old songs.

For someone like me who is a multi-stan, this makes being a fan of K-pop a full-time job. For instance, after ENHYPEN’s May 22 mini album release, KARD, a four-person mixed-gender group (yes, they exist) dropped its sixth mini album, “ICKY,’’ on May 23. Funnily enough, CIX, another flawless discographical group, also released its sixth mini album, “Save Me, Kill Me,” on Monday — just a week later. Stray Kids is set to drop a full-length album, “5-STAR,” on Friday. P1HARMONY has a comeback scheduled for June 8. Following that up, ATEEZ is set to release “THE WORLD EP.2 : OUTLAW ‘’ on June 16.

And these are just the groups that I religiously follow.

In all honesty, back-to-back comebacks like this only happen about once a year, and it’s just out of pure coincidence brought on by their companies. But boy, do I get excited when it happens. It’s like the K-pop Olympics.

Some may like to criticize the frequency of releases from groups by claiming that this clearly pushes the “quantity over quality” agenda for fans. Similarly, it could be argued that this is a perfect recipe to burn out artists. And I feel compelled to agree.

However, there are a few factors in place that differentiate the music-making processes K-pop artists and U.S. artists go through to create pieces.

One of the main practices that sets the two apart is the fact that, although it’s becoming more popular and expected, there are still quite a few mainstream groups, like BLACKPINK, that don’t write or produce their own songs. They just perform them.

Those that do write and produce their own pieces, like BTS, Stray Kids and (G)I-DLE, usually receive extensive help either from in-company composers or from outsourcing tracks from across the globe. This, along with the fact that there are multiple members in each group that help in the production process, can ease some of the stress of creating music en masse.

Because of the collaborative effort that’s enacted to make music, songs are released with high frequency without necessarily disrupting the caliber of the pieces. If the music I was listening to was garbage, I wouldn’t have been a K-pop stan for so many years — seven, to be exact.

In terms of burnout from songwriting, as a writer myself I truly understand the strain of writer’s block — albeit I don’t have nearly as much pressure on me to write as a K-pop idol would. If burnout is to be discussed, though, there should be more discourse surrounding award shows, performance showcases and the ridiculous amount of travel and training that is expected from idols. I’m definitely not a doctor, but those have to be taking a more serious toll on the performers than sitting in a studio making music.

All this is to say that being a K-pop stan is something to celebrate: K-pop blows U.S. music culture out of the water.

Daphne Yaman is a junior writing about K-pop in her column, “Non-Stop K-Pop.” She is also the opinion editor at the Daily Trojan.