A “limitless” future is steadily becoming reality; but the shadows of a tumultuous past still linger, and a “year of implementation” awaits for the president to make good on her ambitious plans.

Many things could be said about Carol Folt’s tenure, four years and counting, as president of the University; but it has certainly not been boring. Some of USC’s most drastic changes and actions took place under her watch: the complete closure of in-person instruction, for a year and a half, due to the coronavirus pandemic; the funneling of at least tens of millions of dollars into new initiatives, new facilities and even new campuses; and even more millions to settling some of the most devastating scandals in the University’s history, both during and before her term.

Folt seems to have embraced the controlled chaos of her presidency. In Spring 2023, the phrase “everything, everywhere, all at once” emerged as somewhat of an unofficial slogan — no doubt motivated by the fact that USC alum Ke Huy Quan, who co-starred in the film of the same name, had just won an Oscar for his performance. She repeated it multiple times in her most recent State of the University address. She’s referenced it on Instagram (“@USCedu’s newest faculty are joining a university doing everything, everywhere, all at once,” she wrote in a post Aug. 24). Speaking with Fortune magazine in May, she cited the film as an inspiration for launching the $1 billion Frontiers of Computing initiative.

Even when we sat down with Folt for an exclusive interview one afternoon in August, it was the driving theme of our conversation.

“These are happening everywhere, everyplace, all at once,” she said — referring explicitly to USC’s sustainability efforts, but also putting into recognizable words the underlying point she was trying to make throughout the interview: Her mission as president was not singular, but multifaceted and omnipresent.

This time, though, she was more specific about what those facets were.

“Fix it, build it, do it, sustain it — those are the four processes you’re always trying to do [at a university],” Folt told us. “And I would say that I’ve been trying to do all four of those since the day I walked in here.”

Indeed, the moment she was inaugurated, in 2019, Folt had quite a lot of fixing to do. Calls to rename buildings bearing the name of Rufus von KleinSmid, the University’s fifth president and a staunch promoter of eugenics, had been ongoing for years. Descendants of Nisei students, in particular, who had been deprived of the opportunity to graduate under von KleinSmid, were demanding an apology. USC had also emerged as a central culprit in the now-infamous college admissions scandal codenamed Operation Varsity Blues, the details of which first became public in March of that year. Meanwhile, scores of women were coming forward through multiple lawsuits, accusing former USC gynecologist George Tyndall of sexually abusing them; LGBTQIA+ men also filed suit alleging sexual harassment by Dr. Dennis Kelly. The very day of Folt’s inauguration, the Environmental Student Assembly held a climate strike, protesting what it saw as USC’s refusal to take meaningful environmental action, including divesting from fossil fuels or transitioning to renewable energy sources.

At the time of publication, much of the remedial action is done. The Von Kleinsmid Center became the Center for International Public Affairs, then the Dr. Joseph Medicine Crow Center for International and Public Affairs. (EVK, the dining hall situated between Birnkrant and New North Residential Colleges, was initially the site of a women’s dormitory named in honor of, but not explicitly after, von KleinSmid’s wife Elisabeth. The acronym changed to mean “Everybody’s Kitchen” long before Folt, but we could not verify when exactly.) Folt apologized for the mistreatment of Nisei students, issued more than 100 posthumous degrees and installed a rock garden near the McClintock Avenue entrance as a tribute. In 2021, USC settled with Tyndall’s former patients for a total of $1.1 billion, and with Kelly’s former patients for an undisclosed sum.

As for environmental action, Folt has at least outlined a plan to divest from fossil fuels over 10 years; the University sold one-third of its $313 million portfolio as valued in June 2021, but the remainder has since appreciated to $385 million. In 2022, USC unveiled “Assignment: Earth,” a framework encompassing a number of initiatives, and stated overall goals of achieving carbon neutrality by 2025 and zero waste by 2028 — which, though significantly more ambitious than previous goals, the University nonetheless appears on track to achieve.

With a messy past somewhat addressed — though each of the remedial measures certainly have their critics; and some issues, like the gentrifying force of luxury student housing (exacerbated by former president Max Nikias) persist — Folt seems more than ready to shift gears.

“If you wait three years to get started on the future, you’ve already had three years of students who are already ready for the future that are impatient,” Folt told us.

Really, she said, she had been thinking about the future since the moment she started; the pandemic had just stood in the way. Once that seemed to wane, however, she wasted no time in announcing everything that had been in the works: a $1 billion-plus, so-called “Frontiers of Computing” initiative; a new campus in Washington, D.C.; a vast restructuring of the athletics and health sciences programs; continually increasing financial aid opportunities; and initiatives to further increase diversity among students and faculty (though, with affirmative action now ruled unconstitutional, it remains unclear how USC will proceed); among others.

“I choose to see USC’s future as limitless,” Folt had said in her State of the University address. “I hope when people think of USC, they’ll think of a place where there is excellence in everything, everywhere all at once.”

But there is still much that needs to be done to reach said “limitless” future — and the questions still remain: Can Folt fix what’s left? Can she build it? Can she do it? And, having done it, can she sustain it?

In February 2020, Folt announced that, beginning in the fall, students from families with an annual income of $80,000 or less would have their tuition fully paid by USC. The calculations for this aid package would disregard home ownership.

With this initiative, the University was hoping to target students “who may previously have earned too much to qualify for adequate aid, or too little to afford a top-tier college education,” according to the USC Affordability Initiative’s webpage.

“We really want this to be an institution where great students can attend regardless of their financial background,” Folt said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times after unveiling the initiative. “Education should be the great bridge across income that really is the equalizer and makes our talented, hardworking students able to make real contributions.”

Before coming to USC, Folt was the chancellor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and held several positions within Dartmouth University’s administration, including interim president, provost and dean of faculty. At UNC, Folt was well known to be an advocate for financial aid; multiple scholarships were named in her honor when she left.

“My entire focus has been excellence at any level of income,” she said at a 2018 conference.

In our conversation, Folt told us this prior experience led her to propose the free-tuition initiative as soon as she stepped into her role.

“I started working almost from the first day with my finance team and said, ‘What can we do?’” Folt told us.

Folt also mentioned that she picked $80,000 as her benchmark because it was above the median family income in California.

“I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be amazing if more than half the people in California and, basically, in the United States would be able to be eligible for free tuition?’” she said.

It would be, perhaps, but “free tuition” meant families still had to find a way to pay for other fees such as housing and meal plans — costs that can add upward of $24,000 to the price of attendance, based on USC’s own calculations. (The USC Financial Aid Office told us that most students who would qualify for the initiative should receive external grant aid to cover those other fees.) But the University nonetheless hoped this initiative would drive enrollment upward, especially among lower-income families.

And it seems to have worked: Since before President Folt took office, USC has seen a steady increase in overall enrollment. The University’s total student population rose from 47,310 in Fall 2018 to 48,945 in Fall 2022 — a 3.5% increase. According to the Financial Aid Department, about 3,200 of those students are direct beneficiaries of the Affordability Initiative, and about 35% of them are first-generation.

“Fix it, build it, do it, sustain it — those are the four processes you’re always trying to do [at a university].”

Carol Folt

President of the University

It was, however, recently revealed by an Aug. 24 report from the Office of the Inspector General that USC over-awarded financial aid by a margin of about $68,000. It is unclear if beneficiaries of the affordability initiative are among those who supposedly wrongly received this aid.

But other than this recent revelation, Folt’s drive to enroll has faced another rather large bump in the road: the coronavirus.

Folt’s first chance to demonstrate her impact in enrollment came at the unfortunate timing of Fall 2020, the first semester at USC to be completely virtual, as well as a time when many students across the country — especially those from lower-income families — chose to defer their application or admission to college to avoid virtual learning. As such, enrollment at USC dipped from roughly 48,000 in Fall 2019 to 46,000 in Fall 2020.

Enrollment in Fall 2021 seemed to include those who had deferred admission from the prior year, as the student population rose to 49,000 before dropping slightly in 2022.

USC appears to have done better than most U.S. colleges in overall enrollment trends over the past few years, as changes in enrollment trends were not as drastic as the national average. Folt said she owed the success to a number of factors, but the one she spoke on most was USC’s transfer student program. USC accepts a much higher number of transfer students per year than many other colleges, especially private ones. In Fall 2022 alone, more than 1,000 transfer students began their first year at the University.

“People don’t have to apply [to USC] once and never try again,” Folt said. “So we keep the door open. We expand our tent, by being able to have several ways you can come in. I think that also has been very effective at having people understand that you can get excited about [USC]. Even if you didn’t know about it in your first year you still have other ways to apply.”

Breaking down USC’s enrollment over the years by race paints an intriguing picture. Enrollment of white students at the University has steadily shrunk from Fall 2018 to Fall 2022 — decreasing by 16%. Alternatively, enrollment of Asian students has increased by 19% from 2018 to 2022.

Interestingly, Asian students, along with Pacific Islanders and those who indicated two or more racial groups or who did not indicate their race at all, did not suffer a decline in enrollment in Fall 2020, contrasting to the trend of mid-coronavirus education.

International students, on the other hand, suffered an immense drop in enrollment during 2020 and 2021 — likely because of international travel restrictions, which USC vocally opposed and aggressively lobbied against — despite their numbers trending upward overall. More than 11,000 international students were enrolled at USC in the Fall 2018 and 13,000 were enrolled in Fall 2022, a 15.5% increase.

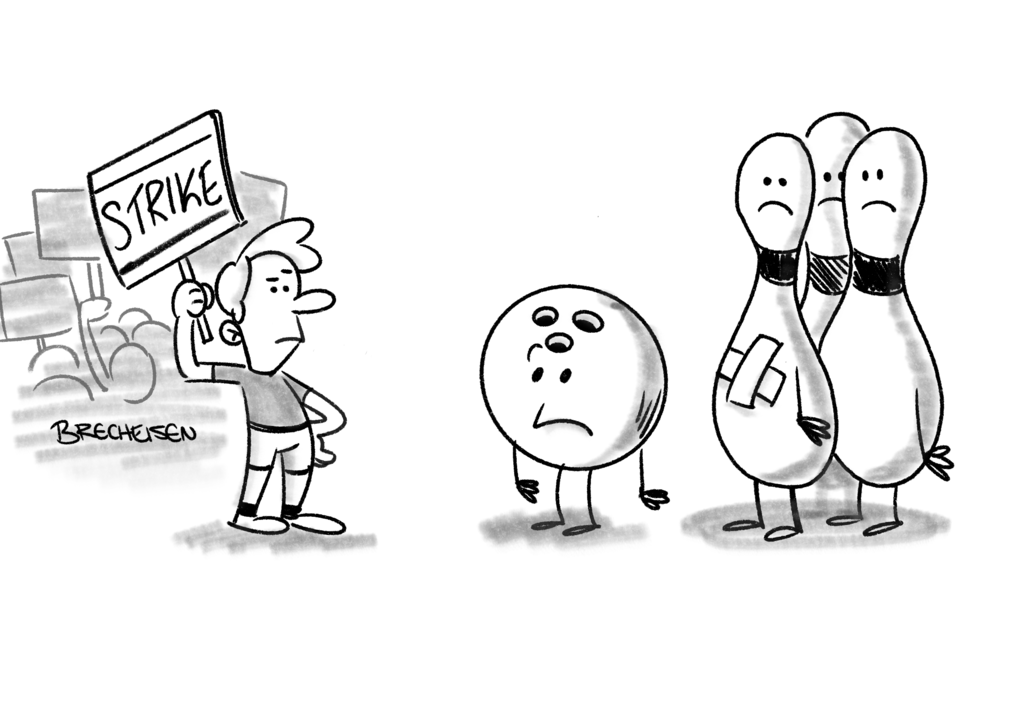

Cartoon: Jack Brecheisen / Daily Trojan

Enrollment of Black and Hispanic students at USC has also risen since 2018, though by a smaller percentage than their Asian and international counterparts. Black enrollment at the University has risen by 8%, while Hispanic enrollment has only increased by 7%.

Since Fall 2020, first generation students have consistently comprised approximately 22% of USC’s freshman class, a University spokesperson said. No data is available on the percentage of international students within the overall population.

While it seems that USC was already breaking from national trends — college enrollment has decreased nationwide by about 9% between 2019 and 2022, falling well behind USC’s 3% bump — Folt entered her tenure with two enormous tasks: keeping her University on track and doing so after a brutal, pandemic-razed year for college enrollment. And if anything can be gathered from this data, it appears she’s managed to do just that, for now.

Yet one thing, again, stands in the way: the repeal of affirmative action. In the years since Lyndon B. Johnson announced the policy, affirmative action has faced a number of legal challenges. Lawsuits argued, to varying degrees of success, that it was a form of reverse discrimination. It was not until this year, however, that the Supreme Court declared in the resolution of two cases that affirmative action programs being used at Harvard and UNC violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment — effectively declaring affirmative action unconstitutional.

On June 29, the day of the decision, Folt released a statement on Instagram decrying the result and promising that it would not result in a change of the way that USC admits students.

“USC has long understood that excellence and diversity are inextricably intertwined,” the statement read. “This decision will not impact our commitment to creating a campus that is welcoming, diverse, and inclusive to talented individuals from every background … We will not go backward.”

When we followed up in late August, asking if USC had any specific plans to ensure diversity in admissions, a University spokesperson said only that “all admitted students meet our high academic standards through a contextualized holistic review,” and that its programs evolve “to uphold our unifying values as the law in this area develops.”

Granted, it is not immediately clear how this law will develop. In the meantime, USC has the opportunity to put its money where its mouth is.

USC “was at zero in 2014” in terms of thinking about sustainability, Dan Mazmanian, a professor at the Price School of Public Policy, told us, in an interview two years ago.

Before Folt, in 2010, the Board of Trustees passed a series of sustainability resolutions under former President Steven Sample, declaring that the University would “maximize” renewable energy and maintain “aggressive” programs for water conservation and waste management. The act was the first of its kind for USC, but gave no specifics as to how the University would achieve such goals.

A few years later, students had also begun protesting the University’s unwillingness to divest its fossil fuel investments and shift to renewable energy sources to no avail.

“Unless it is willing to free itself of dirty investments,” one letter to the editor in 2013 read, “the progress it makes in other areas is only parochial.”

The Undergraduate Student Government established the Environmental Student Assembly in December of that year, beginning what Halli Bovia, then the Office of Sustainability’s sustainability program manager, called a “culture shift with the students.”

But it wasn’t until 2015 that USC established its first Universitywide sustainability agenda with a clear path: a 20% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, a 25% reduction in potable water use, and a 75% waste diversion rate from landfills — all by the target date of 2020.

With just a 5-year scope, however, the plan was far less ambitious and comprehensive than peer institutions. In a 2018 interview, then-ESA co-director Olivia Pearson condemned USC’s plans as “a little vague and kind of just greenwashing the whole thing.”

By the conclusion of USC’s 2020 plan, it had fallen short of its already modest goals by 14%, a discouraging outcome for those who hoped the University would finally take sustainability seriously.

When Folt joined the ESA’s climate strike the day of her inauguration, it was clear something was about to change.

It made sense: Folt has a doctorate in ecology, on top of decades of experience as an environmental scientist. In her previous position as chancellor of UNC, she developed a sustainability campaign, the Three Zeros initiative, which helped focus the university’s efforts on net zero emissions, net zero water use and zero waste to landfill.

In the same month as her inauguration, Folt reinstated a program that subsidized 50% of public transit costs for USC employees and established the Presidential Working Group on Sustainability to help map out the University’s sustainability agenda for the next decade. Mazmanian was appointed the group’s inaugural chair.

“When I was offered the position at USC, I actually thought a lot about whether this was a place where sustainability could really be part of building the future,” Folt told us. “I was so excited when I got here and found, of course, students were active. But in my first few months, when I asked [Mazmanian] to run the sustainability task force, I started finding out that it was already there in people’s minds — but it had never been brought together.”

Change was quick to arrive after Folt assumed her position. After years of protest, the president finally met with students calling on the University to divest from fossil fuels, in early 2020. One year later, the Investment Committee of the Board of Trustees announced that USC would embark on a 10-year journey to divest its $227 million in fossil fuel investments.

Until 2021, the University notably did not participate in the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment and Rating System, used by more than 1,000 colleges and universities to assess their sustainability progress. Until that point, the University also lacked a chief sustainability officer to help steer its efforts.

2021 marked a significant step forward as the University hired its first CSO, Mick Dalrymple, in July. Three months later, USC finally joined STARS, earning a silver rating. STARS ratings include bronze, silver, gold and the highest rating: platinum.

“A Silver rating is higher than we were initially expecting and reflects the hard work that many members of our community have put in over the last few years,” read a statement released in July 2021 from Dalrymple’s office.

Most peer institutions, including UCLA and the University of Michigan have earned at least a gold rating as of publication.

The culmination of the PWG’s efforts arrived in April 2022 with Assignment: Earth — a comprehensive sustainability agenda comprising the University’s new Sustainability 2028 framework, a flashy new brand identity and a host of fresh initiatives that fell under the new program. The 2028 plan set ambitious sustainability goals, including carbon neutrality in scopes one and two emissions by 2025 and zero waste and a 20% reduction in potable water use by 2028.

Cartoon: Frances Xu / Daily Trojan

Cartoon: Frances Xu / Daily Trojan

“It’s a big assignment, but we’re all in,” Folt declared in an interview with USC News around the time of its launch. The phrase would become something of a rallying cry for sustainability at USC and a product of the optimism that marked Folt’s administration.

Though it fell short of its goals in 2020, USC now appears on track to make good on its promises. Water use is down 15% and carbon emissions down 31% from a 2014 baseline as of 2022. USC also logged a 47% campuswide waste diversion rate in the same year, partially owing to Folt’s sense of urgency in pushing “zero waste” events. The first was a community luncheon following her inauguration in 2019.

To achieve its carbon neutrality goals, USC entered into a landmark solar energy agreement with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power in September 2022, which is projected to reduce roughly one- fifth of the University’s greenhouse gas emissions. A quarter of USC’s energy now comes from solar power, which students had demanded since at least 2014.

“We were able to get real changes in some of our contracts so that we could change our carbon free goals and move them up to 2025 within the first year and a half,” Folt said about the shift in operations. “It’s another example where, when you brought in the whole, each one of those areas aligned in their direction, things started happening so fast.”

Folt also pushed for additional funding toward sustainability-related research grants, scholarships and fellowships. The Presidential Sustainability Internship Program, a testament to her effort, helps match students with projects supporting the University’s sustainability agenda.

Engagement efforts ballooned after Assignment: Earth made its debut, now encompassing the annual “Green Week” of sustainability-related events, which launched in September 2021, and the complementary “Earth Month,” beginning in April 2023. This past Wednesday, Folt led the grand opening of USC’s Sustainability Hub, located in the Wilson Student Union, which intends to energize and focus collaboration on sustainability.

“What’s so meaningful to me is that this is the Student Union,” Folt said during the hub’s grand opening. “It has all students coming in and out all the time from every area, and now, they can all collaborate with each other on this shared passion for sustainability. That’s how we can make USC a gold standard for sustainability and education, research, innovation and operations.”

The Hub was an “early dream” for students and staff, Folt told the audience.

“They wanted a place to gather to collaborate and share a love of the natural world,” she said. “And here we are.”

The culmination of these efforts is a fundamental shift in the culture of USC. In 2023, a survey of roughly 2,300 members of the USC population published by the Office of Sustainability found that more than half of respondents usually engage in actions to reduce their impact on the environment. Prior to Folt’s administration, more than half of the 411 respondents in a USC survey published in July 2019 were unaware of how to engage in sustainability efforts at USC.

Four years into Folt’s presidency, USC is seeing early payoffs from her ambitious leadership, though the sudden change in pace has resulted in tradeoffs to make pace with ambitious goals and conflicts with longstanding weaknesses of the University.

For instance, USC will likely not meet its goal of achieving carbon neutrality in 2025 through its own decarbonization efforts. To meet the target date, USC will put money toward controversial carbon credits — in which the University will invest in external projects that reduce carbon emissions elsewhere — that count as “credits” toward offsetting USC’s leftover emissions by the target date. Carbon credits are controversial because they make it difficult to verify emissions reductions in offset projects and because it allows institutions to continue harmful practices.

As recently as last year, USC used 1.4 times the state-mandated allowance for water as the 2028 date grows nearer. When it comes to divesting its fossil fuel investments, though the University already sold $102 million, the worth of its remaining investment has appreciated to $385 million, complicating the process.

How Folt’s administration will address these issues in the future is far from an open question. Folt’s first four years, from her inauguration to the launch of Assignment: Earth, to the debut of the Sustainability hub tell the same story: When it comes to sustainability, Folt is “all in.”

“The things that I think have been really successful are when — I’ll say my administration — have been able to tap on things that the community really believes in,” Folt told us. “Does it mean every single person agrees with everything? No. But we did have a community that wanted to be known for being able to be a place of opportunity.”

She listed a couple of examples: the renaming of Allyson Felix Field, the renaming of Joseph Medicine Crow Center for International & Public Affairs — largely symbolic moves in which she seeks to differentiate herself from past administrations, and past controversies, in her commitment to diversity. Others, though not explicitly mentioned, also fall into this category, such as the appointments of the Gould School of Law’s first Black dean, the first woman athletic director (which took place after our conversation with Folt) and the first Latine provost. Of course, more concrete measures are underway, but those symbolic moves seem to be the ones that garner the most public attention, and support.

“That’s a real strength,” she said. “When you have a community that really wants change, then you’re able to move it forward a lot faster.”

But, she insists, concrete measures are still a priority.

“You can say it, but then can you actually do it?” she said. “We’re calling this ‘the year of implementation’ in our internal team, to make sure we’re really implementing these great things we’re saying. And I’m excited about that.” ❋

Nathan Elias is an assistant news editor at the Daily Trojan. He is a sophomore majoring in journalism.

Jennifer Nehrer is an assistant news editor at the Daily Trojan. She is a sophomore majoring in journalism.

Jonathan Park is the digital managing editor at the Daily Trojan. He is a junior majoring in applied and computational mathematics.