UNCULTURED

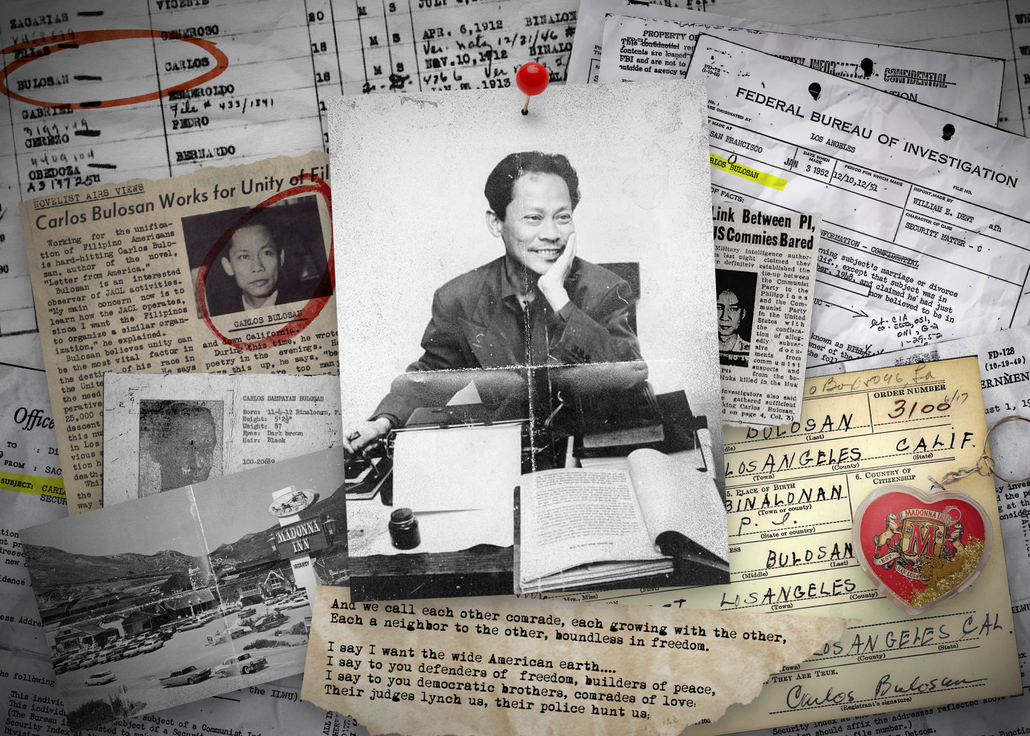

Carlos Bulosan on the nation’s heart

The Filipino-born writer arrived in the U.S. in 1930. Ninety three years later, his work remains relevant.

The Filipino-born writer arrived in the U.S. in 1930. Ninety three years later, his work remains relevant.

“Yes, I will be a writer and make all of you live again in my words.”

– “America Is in the Heart,” Carlos Bulosan

What does it mean to be American? Generations of immigrants have come and gone, shores have been landed upon, homes erected — yet centuries later, the question remains. It’s a question Carlos Bulosan wrangles with in his personal recollections, stories, poems and novels, a question I also glaringly face as I figure out my role in a nation that is taking increasing notice of my people.

A Filipino American author of brief acclaim during the 1940s, Bulosan’s books, such as his seminal “America Is in the Heart” or “The Laughter of My Father,” are mentioned every now and then, but attention upon him remains limited. Perhaps this is more indicative of American society than any willful ignorance; after all, Filipino Americans are a minority within a minority.

But this is changing.

Asian Americans are the fastest growing ethnic and racial group in the U.S., according to the Pew Research Center in 2021. To remain ignorant of a subsection of people playing an increasingly large role in American society is to remain ignorant of the U.S. itself, and Bulosan is a witness, tribune and testament to histories relegated to the margins of American textbooks.

Bulosan, a wispy man barely 5 feet tall and under 100 pounds, would have much to say about the U.S. today. The afflictions one sees in New York, where I’m from, or Los Angeles would not be unfamiliar to him. Arriving in 1930 during the Great Depression, Bulosan saw the dismal conditions that immigrants and low-income individuals were exposed to.

From the nation’s underbelly, Bulosan recorded the traumas Filipinos faced. As he wrote in one letter to Dolores Feria, “I feel like a criminal running away from a crime I did not commit. And the crime is that I am a Filipino in America.” The color line was clear to Bulosan. In his side of America, there were slums, tenements, brutality, and the everyday indignities that weather the poor and racialized of this country.

In his works, Bulosan centers on an unseen subsection of the American poor: Asian Americans. The “model minority” myth has hidden some of our nation’s poorest from full view. In New York, one in four Asians lives in poverty, according to a 2020 study conducted by Robin Hood with Columbia University. Asian Americans also have the largest class gap of any racial group according to the Pew Research Center in 2018: the top 10% of Asian American earners make more than 10 times the income of Asian Americans in the bottom 10%.

Asian Americans are Americans after all; we are not impervious to the social ills the United States suffers from.

Bulosan’s work corroborates what I observed in my youth. In Flushings or the Bronx, where I could see older Asian folks still working, still breaking their backs in cramped apartments, toiling away in food deserts and underfunded zip codes, Bulosan was a revelation to my younger self; he showed me that I wasn’t imagining it, that there was a basis for what I was observing.

These stories fumbling in the dark are brought to life in Bulosan’s fiery prose. In “Freedom From Want,” Bulosan confirms the inequities Filipinos faced: “We are bleeding where clubs are smashing heads, where bayonets are gleaming. We are fighting where the bullet is crashing upon armorless citizens, where the tear gas is choking unprotected children … Where the honest man is hanged because he told the truth.”

He continues, “If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.”

Bulosan intimately understood the life of displaced and newly-arrived people in America. He spoke to those who find themselves in the domestic heart of a nation they had only seen from afar. The U.S. was now home, and no matter where one is, home is a complicated matter, an irrevocable condition that one must always feel.

Bulosan, who yearned to be part of the U.S., died of pneumonia in Seattle in 1956. He was in his early 40s, leaving behind writings attesting to the price Asian Americans paid to have their tenuous position in American society today. What Bulosan could do for his people, as his friend P.C. Morantte says, was to “record their lives, their fears and their loves, through his writings.” He was a social chronicler, playing the role of the American witness and speaking truth in the light of day.

More than anything, Bulosan was driven by humanist concerns for the betterment of American society. As Morantte wrote in “Remembering Carlos Bulosan,” “We both knew for facts many brutal incidents which had happened to others … especially striking workers in various fields who were savagely abused … Carlos’ heart had bled for them, cried for them. That is why he did not hesitate to claim the barbarities done to them — to all underdogs, to all the oppressed, to all the poor fighters against abuses by the rich and powerful as also his own.”

In the aftermath of the country’s “Hot Labor Summer,” Bulosan’s indignance remains contemporary. As labor struggles enflame several private and public sectors, as the 21st century color line is continually exposed, Bulosan remains a guide on the bloodied sheets of American history, detailing what we are, where we were and who we can be. Ninety three years after his arrival, I continue to hope for freedom for all in the U.S. Bulosan never quite lost faith in.

“America Is in the Heart” ends with a final confirmation of the struggle Bulosan’s people faced: “I knew that no man could destroy my faith in America that had sprung from all our hopes and aspirations, ever.”

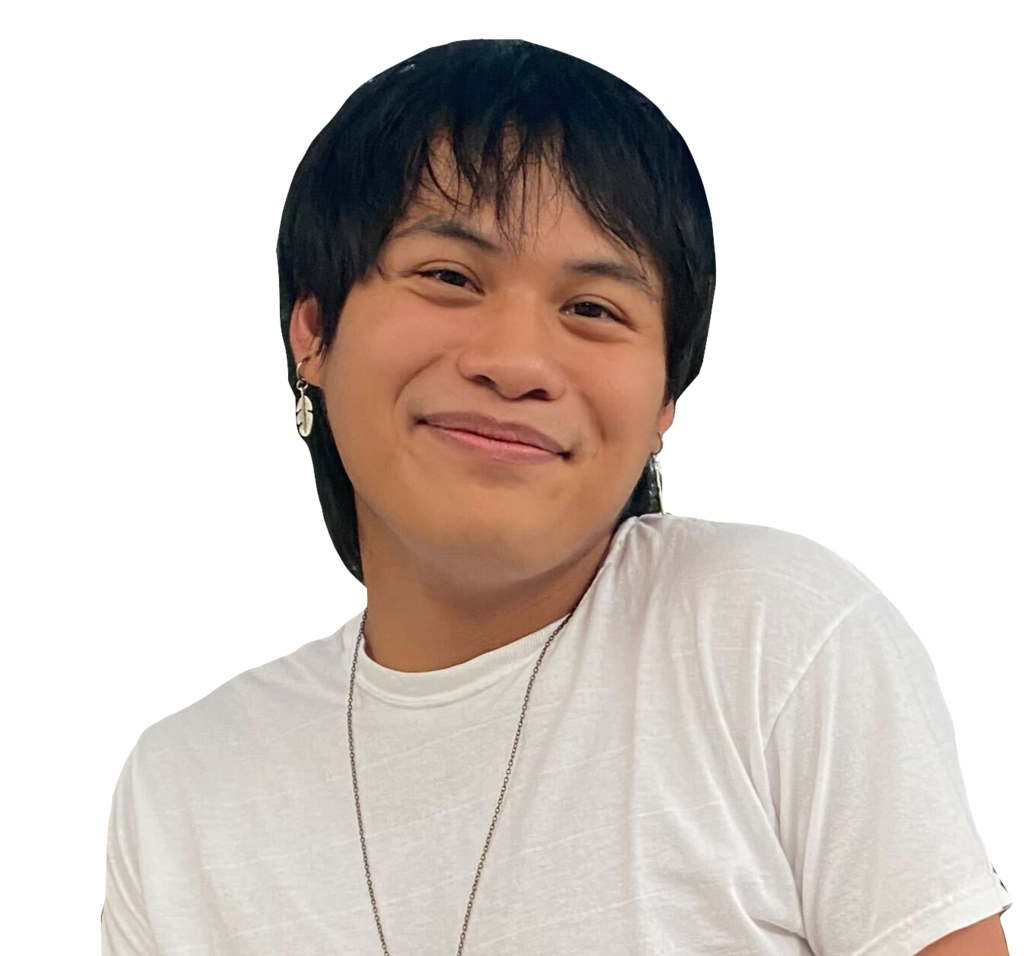

Shane Dimapanat is a junior writing about not-talked-about-enough, obscure media that should be culturally accessible. Their column, “Uncultured,” runs once a month on Thursdays.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the compensation they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: