Middle Easterners don’t fit into the ‘white’ box

Middle Eastern and North African individuals deserve their own racial category.

Middle Eastern and North African individuals deserve their own racial category.

Choosing an option on a questionnaire is usually an easy task, whether it is taking a multiple choice exam for one of your classes or choosing which milk to add to your mobile ordered Pumpkin Spice Latte at Starbucks. While getting a question wrong on an exam may feel like the end of the world, or you may claim your drink is “life-changing,” in reality, these types of choices aren’t meant to — and therefore don’t — represent fundamental parts of your identity. However, when you must make a choice that is meant to represent a fundamental part of your identity, but it doesn’t, the effects can be truly detrimental.

This experience is the reality of many people of Middle Eastern and North African origin when filling out racial questionnaires — even those for the United States census.

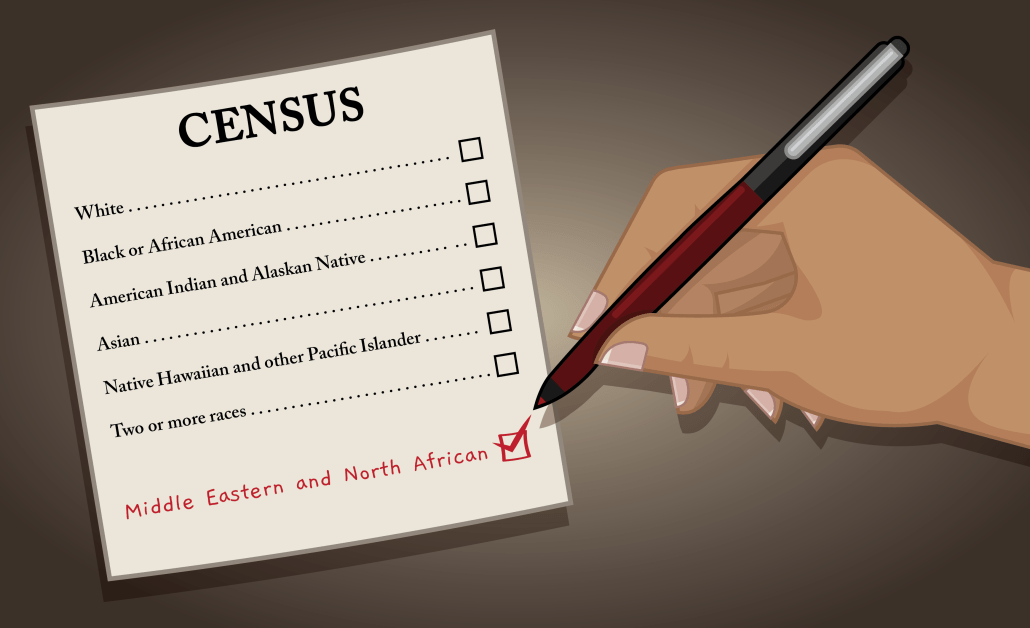

The U.S. census (along with many other racial questionnaires, such as ones used for school and job applications) gives the race options of White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and Some Other Race. Specifically with regard to the white racial category, the U.S Census Bureau defines white as “having origins in … Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa,” and by doing so, categorizes Europeans, along with MENA people, as white.

USC also doesn’t provide a MENA racial category. In USC’s student demographics report for the Fall 2022 freshman class, USC only reported on the categories of Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic, White/Caucasian, Other and International. However, USC provided a Hispanic category, thereby deviating from the U.S. census. Considering USC’s Undergraduate Student Government finally recognized the Middle Eastern North African Student Assembly last fall, USC still not having a separate MENA category seems hypocritical.

The National Human Genome Institute defines race as “a social construct used to group people … often based on physical appearance, social factors, and cultural backgrounds,” establishing that major differences in these factors are what distinguish racial groups from one another. In examining MENA people from this lens, it becomes apparent that their placement into the white racial category is ill-fitting as they are distinguishable from the majority of white people in each one of these elements.

Many MENA people harbor different physical features from their white counterparts, with their appearance instead often being more analogous to features of other underrepresented races. Specifically, according to Brittanica, many Middle Eastern people “resemble African Americans or Africans in their skin colour, hair texture, and facial features” and are even “frequently mistaken” for them in the U.S.

Skin tones, hair textures and facial features that can resemble Black people therefore distinguish many MENA people from the physical appearance of the majority white race, which has been historically and socially constructed as the antithesis of Blackness.

The resemblance of MENA individuals to other underrepresented races also helps to contextualize social factors and cultural backgrounds, which continue to distinguish them from white people of European descent.

Significantly, research from 2022 published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that MENA people experience social inequalities and challenges that are more aligned with underrepresented racial populations of color than of white populations. For example, their research discovered that people in this group “are more likely to live below the poverty line” and “report rates of discrimination higher than Whites, and on par with other groups of color.”

Beyond people of MENA descent often being viewed and treated as different or less than white, they themselves also generally view their racial identity as discernable from whiteness.

Of the MENA people surveyed in the same study, “only 11% identified as exclusively White when offered a specific MENA category,” with most self-identifying as MENA when the opportunity was given to them.

MENA peoples’ lack of self-identification as white when given the option to identify as MENA emphasizes how the people of this community feel: They do not belong in and are not truly represented by the white racial category.

Continuing to categorize MENA people as white on questionnaires abandons this community and makes it vulnerable to further inequality and discrimination. Ultimately, this leaves MENA people misrepresented, unrecognized and essentially powerless.

To combat this, organizations that administer racial questionnaires — including USC — should validate this group’s rightful and unique identity by establishing Middle Eastern and North African as its own racial category, separate from white.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: