Celebrating South Korean science fiction

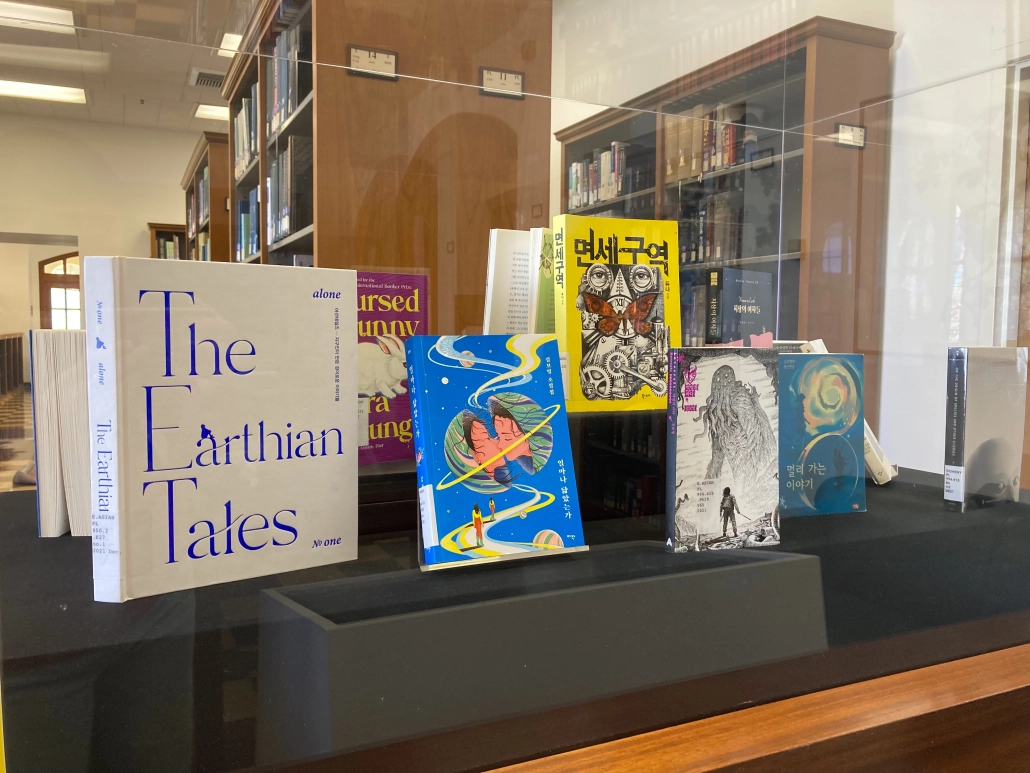

Doheny’s East Asian Library focuses on futuristic media in their recent exhibition.

Doheny’s East Asian Library focuses on futuristic media in their recent exhibition.

Tucked in the corner of Doheny Memorial Library’s first floor is the East Asian Library, which dedicates itself to integrating East Asian perspectives into USC’s literature and culture. This year, the library has gone beyond its typical print and video archives to promote a genre that’s new to the academic scene: science fiction.

The exhibition “Sixty Years of South Korean Science Fiction: Selections from the USC Korean Heritage Library’s Science Fiction and Fantasy Collection” showcases creative work from the genre across disciplines, highlighting how science fiction became a medium for marginalized voices to voice their truth in a censored society. Many authors used common fantasy tropes to comment on pertinent issues of gender, class and climate while remaining publicly acceptable.

Sunyoung Park, an associate professor of East Asian languages and cultures as well as gender and sexuality studies, curated the exhibit for students to catch a glimpse into how science fiction has become popular in South Korea since the 1960s due to its cult following and dedicated fandom.

As part of USC Libraries’ Collections Convergence Initiative, Park identifies under-researched library collections that she can recommend for teaching opportunities, furthering research or for public outreach events. Through the program, Park gained funding from the Korean Heritage Library to collect South Korean science fiction and with support from Korean Heritage Library director Joy Kim and its librarian Jungeun Hong.

“In Korea, genre fiction has long been ignored,” Park said. “I have identified these more minor, fandom-oriented publishers that are dedicated to producing science fiction and fantasy books.”

Park consulted with the East Asian Library’s head librarian, Tang Li, who saw that students’ library use was declining after the pandemic. Li and Park decided to create “Sixty Years of South Korean Science Fiction” in their efforts to physically bring more students to the library and broaden their knowledge of the genre.

Park described a “boom” in South Korean science fiction in the 1960s as the country rapidly modernized during the Space Race. Creatives produced a prolific amount of science fiction literature, comics, animation and film, and by the 1970s and 1980s, the genre had become incredibly popular. During these two decades, science fiction matched South Korea’s new developmentalist era, becoming a space for writers to reappropriate the popular genre and express their counter-cultural beliefs.

“Through my archival research, and also personal memory because I grew up in Korea, I was identifying these kinds of isolated, island-like texts from the ’70s and ’80s,” Park said. “It may not be full-blown science fiction [like] ‘Space Odyssey’ or anything, but the more experimental writers capitalized on this national response to the genre, and re-appropriated its narrative tropes and conventions to advance their critical subjectivity.”

The censorship that South Korea faced during these decades led authors to get creative about sharing their opinions out of fear they might be persecuted. Sin Ki-hwal’s comic series “Here Comes Nuclear Bugs” and Bok Geo-il’s novel “In Search for an Epitaph: Kyeongseong, Showa 62” both indirectly criticize South Korea’s military in the late 1980s.

“[The science fiction genre is] camouflage, right? Because it was at a time of heavy censorship — heavy censorship means not just the books will get banned, but you can actually be dragged to the torture chamber — how do you write around it?” Park said. “Science fiction was a convenient narrative device for them.”

South Korean science fiction experienced another boom in the 1990s, but this time, feminist and LGBTQ+ themes had made their way into the canon. By the advent of the 21st century, writers had turned the conventions of science fiction on their heads, furthering the advocacy possibilities of the genre. Today, at least half of the science fiction from South Korea is produced by women and nonbinary writers.

The exhibit includes key titles such as Bora Chung’s “Cursed Bunny,” which relies on fantasy horror to convey the gravity of gender-based violence, and Park Moon-Young’s “Women on Earth,” which paints a utopian picture to critique the prevalence of migrant brides.

“What’s added [to 1990s science fiction in South Korea] was this rising tide of feminism and sexual minority queer activism,” Park said. “They bring very strong, critical voices. And in fact, they are the most powerful voice now, which is why they are nicely highlighted in the exhibition. And by virtue of that, they amplify the critical tenor of South Korean science fiction.”

Many science fiction authors in South Korea write anonymously, including Djuna, a feminist author who has been described as “South Korea’s enigmatic sci-fi legend.” Their work is included in the exhibit in the cases pertaining to cyber literature and the rise of magazines in the 1990s and new millennium feminist and queer science fiction in the 2000s and 2010s. Writers’ anonymity allows them to explore more revolutionary ideas without backlash.

“It’s an excellent narrative genre through which you can conduct some radical thought experiments on gender,” Park said. “Given how much more suppressed human rights and queer people are in Korea, you can say science fiction is playing a more significant, more important political role there, than here.”

Because science fiction was largely published in underground circles and disseminated by its fans, the East Asian Library’s “Sixty Years of South Korean Science Fiction” exhibit brings an educational lens that the genre has yet to be viewed through. The fandom has long been pushing to make science fiction more accessible in South Korea, which included translating a lot of English works into Korean.

“[The fandom] regarded propagating science fiction as a kind of social mission,” Park said. “Science fiction provides this special narrative potential, and I think Korean critics are just beginning to realize it.”

Through exhibits like this one, Park hopes to expose more students to the tireless efforts of South Korean science fiction authors who broaden the scope of what science fiction can be.

“Culture is generally more activist in Korea and in many non-western parts of the world because they live with this history where the official public discourse of spheres like journalism, like politics, were heavily censored,” Park said. “So then who needs to tell the truth to the public? Cultural intellectuals have really undertaken those tasks. That tradition is still alive.”

“Sixty Years of South Korean Science Fiction: Selections from the USC Korean Heritage Library’s Science Fiction and Fantasy Collection” is on display in the East Asian Library until May 10.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: