Southeast Asians need their own data option

Data disaggregation is the key to understanding the Asian American experience.

Data disaggregation is the key to understanding the Asian American experience.

The first time I ever saw a “Southeast Asian” option on a form was actually this school year with the Daily Trojan. I was so used to seeing just “Asian” or only the options between South and East Asia that it felt unnatural clicking the box. In my heart, I am confident in identifying myself as Southeast Asian and I introduce myself as such, but to see it on a survey for data is completely different. However unexpected as this was for me, it was a pleasant surprise, and one I hope will become the norm.

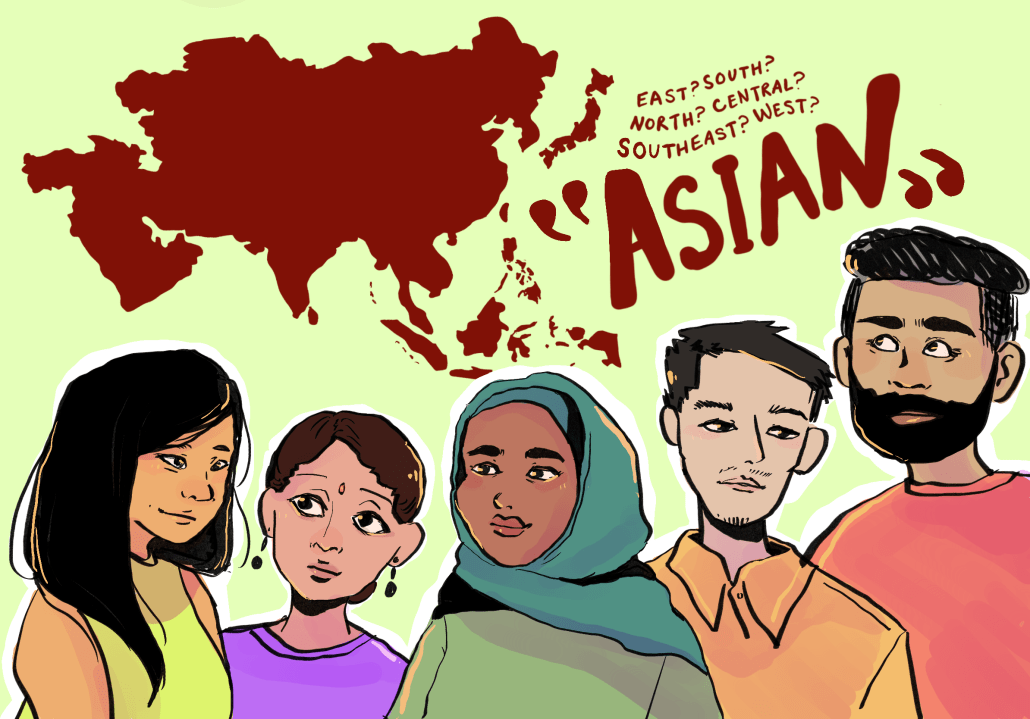

Asia is the world’s largest and most populous continent, but despite how enormous and diverse the continent is, all of its peoples often just get lumped into one category in the U.S.: West Asians, Central Asians, East Asians, South Asians and Southeast Asians all just become “Asian.” On the surface, it’s not wrong or inherently problematic. They’re all from the same continent, so they are all Asian. Simple. But the real problem arises when the data from these surveys or forms that only use “Asian” are used to draw conclusions about the Asian experience in the U.S.

For instance, Asians in the U.S. have a poverty rate of 8.2%, below the national poverty rate of 11.5%. They are also the racial group that earns the highest median income in the US, and more than half of Asian Americans have at least a bachelor’s degree. Based on this alone, it looks like Asians have it pretty good in the U.S.; sometimes, they’re even doing better than their white counterparts! However, this isn’t the full story.

Southeast Asian Americans, compared to the “Asian” data, tend to have higher poverty rates, make less money on average and are less likely to have post-high school education. Because they are a minority within a minority, their data gets distorted by larger Asian groups, making it difficult to see that they actually have it worse than the national average in many aspects of their lives. When government or nonprofit organizations look at data for Asian Americans to plan out programs to address disparities, they might not allocate the necessary resources to certain groups like Southeast Asians because their needs are covered up by the Asian label.

I’ve long known about the problems grouping all Asians together can bring. When I was in high school, I ended up having a falling-out with one of my friends, who was Chinese, because we were arguing over how privileged or not Asian Americans were. She told me I was overexaggerating the oppression and disparities Asians and other racial minorities experience.

After all, from what she knew Asian Americans were prospering, so there’s no way that the U.S. could be an unlevel playing field in terms of race. Other minorities shouldn’t have to rely on things such as affirmative action or diversity, equity and inclusion efforts to succeed; they just need to put in the work like Asian Americans have to get ahead. Part of me felt sad that she lost herself in the “model minority” myth, but most of me felt angry.

It was frustrating because I knew what the statistics said about being Asian in the U.S. didn’t fit my family’s experience, but at the time, I didn’t know why that was. I just knew that there was no way my family could be the only one who didn’t fit the narrative. It was not until years later that I discovered what was behind this erasure: data aggregation, or taking multiple data groups and summarizing them as one.

Thankfully, as demonstrated by the survey I took last semester, things are improving because of advocacy work across the nation. Southeast Asian organizations have been working for years to pass data disaggregation acts to achieve data equity, which is key to finally addressing the discrepancies of Southeast Asian demographic data in the U.S. Data disaggregation benefits everyone under the Asian label, and especially under labels like “APIDA” or “AANHPI” that have even worse data aggregation.

When data is separated by specific ethnic groups, people are able to better understand their needs and give them the resources that they deserve. Until this happens, though, I — like many other Southeast Asians — will continue to advocate for ourselves and the many other groups that deserve to have their individual voices heard. It is with pride that I say I’m not just Asian; I’m Vietnamese. All I ask is the chance for me to say it.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: