With the new year comes a yearning for home

As Tết approaches, I am reminded of why it means so much to me and my family.

As Tết approaches, I am reminded of why it means so much to me and my family.

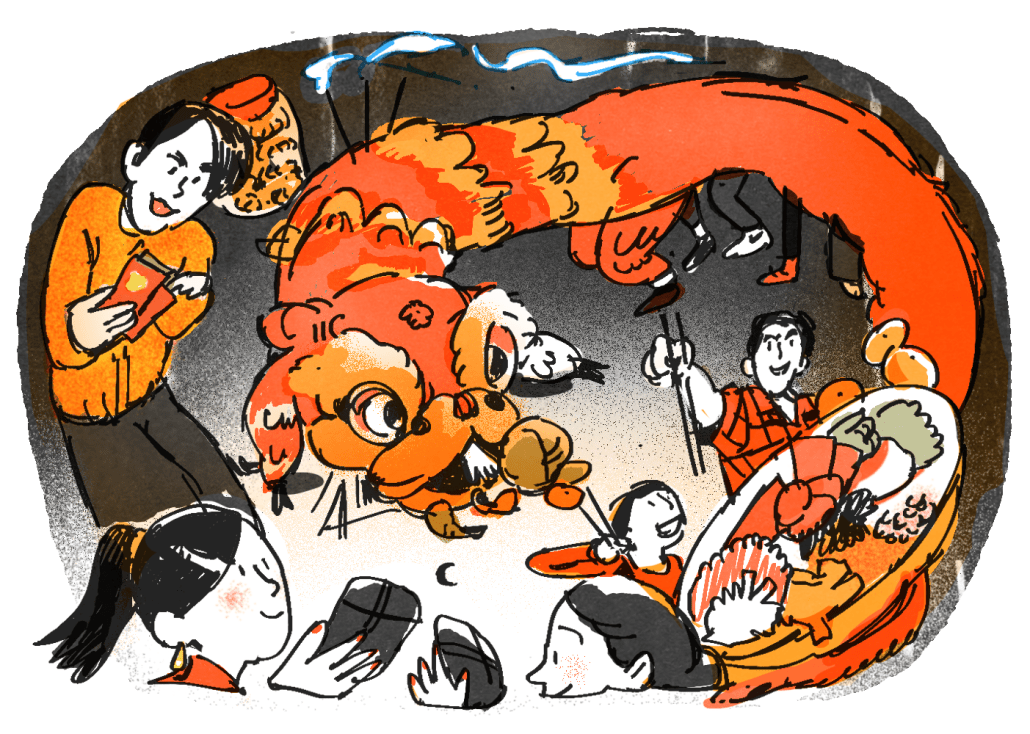

In Vietnamese communities all across the world, this Saturday will mark the biggest holiday of the year: Tết, the lunisolar new year. People take a break from work, meet with family and friends and spend time together with traditional food, games and practices. One of the most important parts of celebrating the new year is the idea of homecoming — returning to your hometown to see your relatives and those you grew up with.

For my family though, along with many other overseas Vietnamese families, this tradition of returning home isn’t exactly practiced conventionally.

My mother’s family had lived in Vietnam for generations. With relatives living close to one another, either in the same house or the same village, Tết celebrations were easily organized. Family members would come together, usually at the eldest relative’s home, and graves were always close by to visit those who had passed on.

The first generation to experience a change from this was actually quite recent, as it was that of my grandparents, only two generations ago. My grandfather and grandmother moved from the north of Vietnam because of growing hostilities where they lived.

Though unable to return to their “home” for Tết, they were still together and developed a new sense of what home was. Their home in the agricultural fields of the north was now in the industrial city of Saigon in the south. It might have been different, but nonetheless, they were a family and willing to both create new traditions and maintain old ones.

However, soon an even more drastic change came. With the end of the Vietnam War, violence reached my family’s new home in Saigon, known after the war and today as Ho Chi Minh City.

To try and escape the conflict, they took whatever money they had to get boats from the local fishermen and used them to escape the war zone. Of the hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese war refugees who left by sea, today called the Vietnamese boat people, my family was one of the lucky ones. The majority of my relatives were taken in by vessels from other countries, though not all the same ones. Some ended up in Australia, others in Japan, but for my mother and her direct relatives, they ended up in the United States.

For a long time, just surviving in a new country was the main goal of my family. It took time for them to reach a point where they could focus on other things besides just making sure everyone was alive and well. After all, forcibly leaving your home country, living in a refugee camp and knowing that your family has been split apart are all very traumatic experiences.

Though it took years to finally establish themselves and start reconnecting, their work paid off. One by one, they were able to find one another even across the world and establish a network that still impresses me today. We have our own family website, yearbook and regular reunions all to make sure that we can keep in touch with one another. And of course, we celebrate the new year together, too.

Today, there’s no real hometown for us to return to, and it’s difficult to get people from all across the world to have the time to meet up during Tết — especially considering how the majority of us don’t get time off for the holiday. Instead, we make do with what we have and have multiple local reunions rather than a single global one.

For me, this means that this weekend, I’m going to Orange County to meet up with my relatives who live nearby. We’ll exchange li xi, eat banh chung, play bau cua ca cop and even pay homage to our country of residence by watching the Super Bowl.

In the hectic life of being a college student, this is a long-awaited break for me and also a good reminder to ground myself by remembering where I came from. For our family, homecoming isn’t like in Vietnam, but it’s just as meaningful. Wherever our family is, that’s home; it doesn’t matter whether it’s in Vietnam, the U.S. or any other part of the world. So, as this weekend approaches, I get to put everything aside for a moment. I get to take a deep breath, center myself, and finally, I get to go home.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: