For better or worse, squirrels have become a staple of campus life. News editor Nathan Elias and associate managing editor Reo examine the history of these ubiquitous creatures.

By NATHAN ELIAS & REO

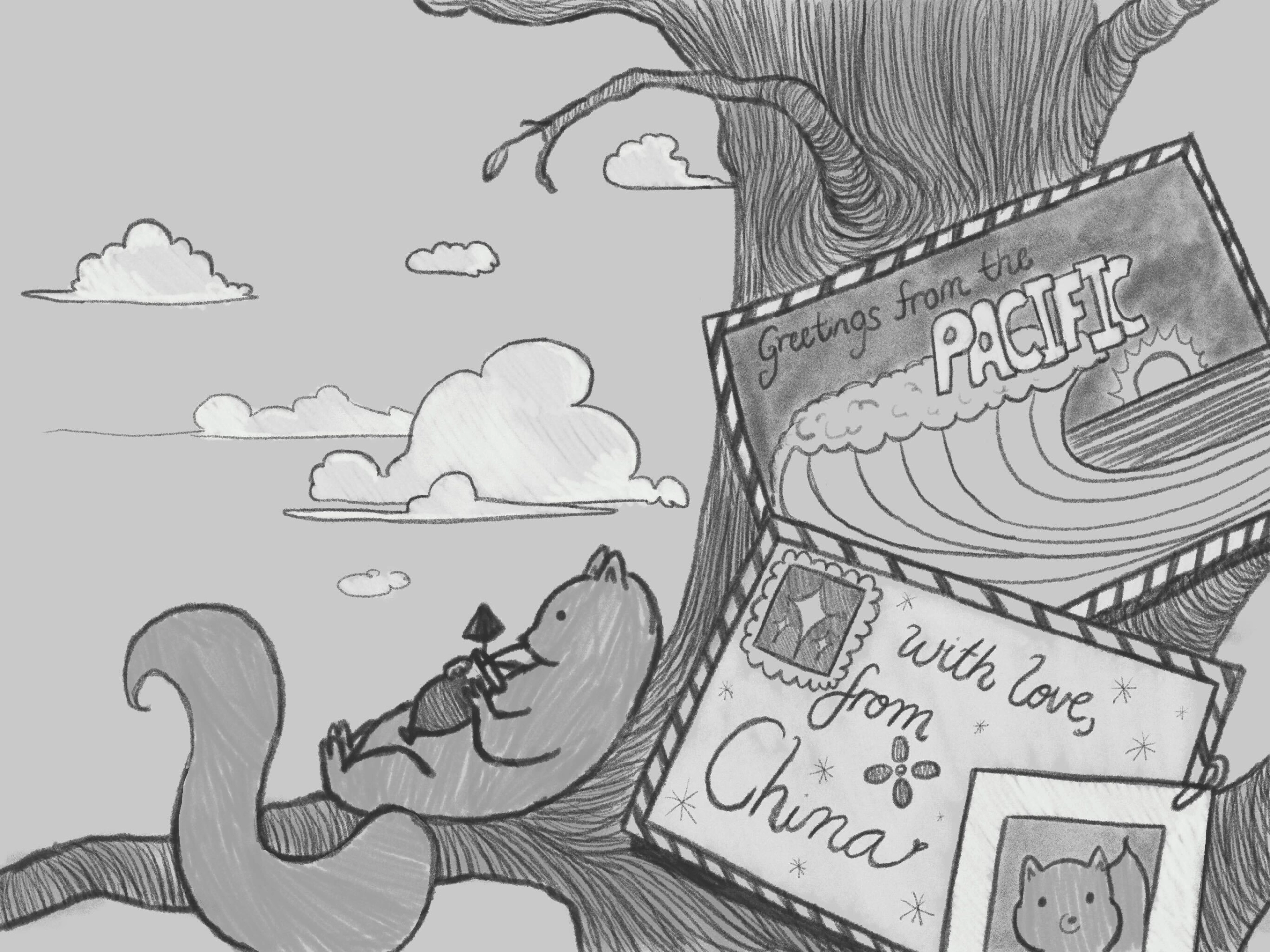

Cover art: Shea Noland / Daily Trojan

The days are getting longer, and the University’s favorite mammals are coming out of their nests more and more. You might see them skittering around campus, scrounging for any nibble of food they can get their paws on. After fattening up on their stash over the winter, it’s time for them to fend for themselves once more.

The mammals we’re talking about, of course, are students.

Coming in at a close second for USC’s favorite mammal is the beloved campus squirrel. Unfortunately, a number of them seem to have been misplaced.

The University takes special care to keep an eye on our campus’s lovely critters. So much so that in 2019, a class began to track them.

Matt Dean, an associate professor of biological sciences, and Jim Dines, an adjunct assistant professor of biological sciences, formed the “Mammalogy” class to learn more about the squirrels on campus and teach students in the process. We sat down with the mammalogists to learn more about their endeavors.

“Our objective was always to give students hands-on experience doing fieldwork,” Dean said. “It’s a little bit hard to do fieldwork in urban Los Angeles, so this was our solution to it, and it’s been really fun.”

As an added bonus, the professors were able to compile data on one of the University’s oldest populations.

It probably wouldn’t surprise you to know that squirrels don’t traditionally thrive in the concrete confines of a place like South Central. Though, like many other college campuses, USC has been a safe haven for squirrels for decades.

The abundance of plants, shade and Cheetos make the campus an ideal home for squirrels, so it’s no surprise that squirrels are an extremely common sight on campus and the target of the professors’ tracking efforts.

“It’s been ideal,” Dines said. “These squirrels are active during the day — diurnal, in the technical sense — and they’re on campus, which is an extra bonus.”

Dean made sure to add, “And they have tremendous personality.”

Dines continued, “It was just the ideal candidate for an organism that students could easily study. And, of course, being mammals, it ties in with our topic.”

The class began in Spring 2019 as a miscellaneous “Special Topics” biological science class. Two years later, the class became its own, fully fledged course, integrated into biology majors’ curricula. Dean and Dines stayed with the class — and the squirrels — over the years since.

“In the very beginning, what we did was we put ear tags in squirrels,” Dean said. “And then, the idea was, the students would go out with binoculars and try to observe them. And that failed miserably. Mostly because as soon as we ear-tagged a squirrel, we never saw the ear tag again.”

Eventually, the professors refined the process.

“It kind of evolved into eventually putting radio collars on them so that we could track them even if they weren’t visible to us,” Dean said.

After the change, students went out into the field with more advanced equipment than binoculars to track the squirrels.

“They have this little tiny collar that emits a beep every two seconds,” Dean said, “and we have to have a gigantic antenna hooked up to a battery [in order to] hear it.”

Despite its unwieldy size, the equipment provided students with an accurate experience of gathering data in the field. Students in the class like Kate Douglas — a senior majoring in biological sciences with an emphasis in ecology, evolution and environment — said the exercise provides hands-on fieldwork experience.

“It’s a valuable skill to have as a biology major who’s not pre-med and who’s more interested in that ecology side,” Douglas said.

Others like Quinn Fagersten, a research lab technician and former teaching assistant for the class, see its applications beyond individual students, to the campus as a whole.

“[The research] also helps us know: ‘How can we create a campus that either deters this wildlife or, hopefully, helps us live in communion with them a little bit better?’” Fagersten said.

If you ask anyone on campus, the latter is much more likely. For instance, USC community members have made it a habit to feed the squirrels.

“[The squirrels] are so overly familiar with people — I can’t stand it,” Fagersten said. “I will sit and watch people feed them, because they think it’s cute … That’s a wild animal. You should not be doing that.”

Under California law, it is illegal to feed wildlife — including squirrels. Dines said feeding squirrels leads them to become accustomed to being fed and can increase aggression.

Douglas said an unlucky encounter with a squirrel could be devastating. So devastating, she said, it might cause a disgruntled student to go on a rampage on Instagram calling to euthanize all USC squirrels.

“I’m gonna be doing a citizen’s arrest anytime I see it happening,” Fagersten said.

The squirrels are so well integrated that their diet and lifestyle are nearly indistinguishable from fellow students and staff — they wander around campus, sleep in the grass and eat snacks — but most squirrels on campus are not native to the area.

Amelia Neilson-Slabach / Daily Trojan

Before the 20th century, the eastern fox squirrel — an orange-furred tree squirrel that is now ubiquitous in L.A. — was largely unknown to the area. As the name implies, the eastern fox is native to forests ranging from the eastern U.S. to northern Mexico.

Shortly after the turn of the century, the Sawtelle Veterans Home — a facility near modern-day Westwood that housed veterans from the Civil War, the Spanish-American War and other conflicts — became one of the first places in L.A. where humans and the eastern fox squirrels lived in harmony.

Until it was time to eat them.

As the legend goes, the veterans brought the squirrels to Sawtelle and kept them like how “people who are not farmers sometimes kept chickens,” an article in Nautilus stated. Once it was time for the squirrels to stop being friends, veterans turned them into squirrel stew.

Dines told Nautilus that hospital administrators soon took issue with how the squirrels used up resources at the veterans’ home — they survived off eating table scraps — so they decided to release the squirrels into the wild.

Little did they know that this, combined with other efforts to spread the squirrels across the U.S., would allow invasive and incredibly resilient species to soon dominate the region.

The eastern fox squirrel has an omnivore diet that includes insects, fruit, fungi, seeds, young rodents, bird eggs and anything else it can get its paws on. The squirrel also can produce two litters of offspring per year, each containing an average of two to four babies. It makes its nests in hardwood trees but survives well in wide-open areas with sparsely populated trees — like parks and backyards.

Over the next century, the eastern fox squirrel’s traits allowed it to blossom in a region where the western gray squirrel — another tree squirrel species that is native to L.A. — is in decline.

Western grays survive on a limited diet of acorns and fungi that grow from the roots of native oak trees, limiting their range to continuous stretches of forest. The squirrels also only produce one litter of offspring per year, with roughly three to five offspring on average.

On college campuses, the fates of eastern fox and western gray are intertwined: As college campuses and other natural areas cut down their oak population to clear land or replace with other species, the western gray has an ever-shrinking list of places to live and the eastern fox continues to thrive.

In a study of over 536 college campuses published in the Journal of Mammalogy in 2020, 95% of campuses had at least one species of squirrel, but less than half had three or more species.

The eastern fox squirrel’s diverse diet gives it a critical weakness that trackers exploit to study and map them. The “Mammalogy” professors set an unassuming bag of Cheetos or peanuts in a metal wire trap, and once a hungry squirrel wanders inside, the door closes from behind it.

Researchers trap the squirrels to take measurements and affix radio collars to the squirrels’ necks with a unique identifier that students pick up using their antenna.

About 48 squirrels on campus are collared, and an overwhelming majority of the captured squirrels are male. Dean and Dines said this is likely due to increased aggression in male squirrels that makes them more willing to investigate new territories. In the four-year history of “Mammalogy,” only one squirrel has ever been recaptured.

“It just couldn’t resist the Cheetos, right? It knew better, but it just couldn’t resist going in there,” Dean said. “We removed that collar. We put a new one on it. He was like, ‘Aw man.’”

Dean stressed that the collars were minimally invasive to the squirrels and reflected best practices in mammalogy research: The collars are loose enough that you could fit a pinky finger in the gap between it and the squirrel’s neck.

“We’re not two crazy dudes doing weird things with squirrels,” Dean said. “These are absolutely established technologies for learning how a mammal uses its space.”

Every April, students descend onto campus with their large antennae to track squirrels and mark their location on a sprawling map of campus and the surrounding community.

Tracking down squirrels is no easy feat. Both Douglas and Fagersten described it as a game of “Hot and Cold” as students follow the beeping noises transmitted from the radio collars. Sometimes, the same squirrel appears not to have moved for a long period of time. In those cases, students have to investigate further.

“A crazy grad student, he’s even climbed the tree to look up there,” Dines said.

One of the biggest challenges in squirrel tracking has little to do with squirrels at all — it’s students.

“Every single time I went out and tracked, I got stopped by someone, by at least two to three people,” Douglas said. “There was a time that I probably doubled the time I would have spent tracking had I not been stopped so many times. It was to the point where I had a group of four people following me and were like, ‘Can we track them with you?’”

Fagersten said the resulting data isn’t always reliable. In the map where students record the squirrels’ locations, a student noted that squirrel 209, which I have elected to call Scott, was in Associates Park — in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. According to the map, over 20 USC squirrels are hanging out in eastern China.

651, 7/27/2021: “Cool location with lots of shade”

272, 4/8/2022: “peanut shells”

171, 4/16/2022; “Tree south of Norris theater,” placed in the Jiangsu province, China

209, 4/17/2022; “chasing other collared squirrels“

311, 4/20/2022: “Just chilling on a branch”

209, 4/28/2022; “Associate’s Park,” placed in the Pacific Ocean

Dines said they expanded their research to include the Exposition Park Rose Garden and the greater Exposition Park area to investigate how far fox squirrels can travel. The researchers conducted the same process — Cheeto trap, collar, tag — but once they returned, the squirrels were nowhere to be found.

“We talked to one of the head gardeners there, and … they would actually trap the squirrels because they’re pests, messing up the beautiful roses, and they would transport them elsewhere,” said Dines. “When Matt says it was almost like a disaster, that’s why.”

While Dean and Dines uncovered the mystery of the missing squirrels in the Rose Garden, there was still a bigger issue at hand: Every year, a third of the tagged squirrels disappear.

“We don’t know where they go,” Dean said. “I don’t think it’s collar malfunctions. They’re either picked off by a hawk and flown away, too far to be tracked, or … we actually have no idea.”

When the professors learned that there were squirrels missing, they kicked it into high gear to find them.

“One time, we drove all the way around campus, and I was hanging out of the car with the telemetry equipment,” Dean said. “They’re just gone.”

Unfortunately, because of how dated the equipment is, the professors could not retroactively track the squirrels.

“We can’t just be like, ‘Oh, the squirrel disappeared. Let’s just look back at our records to where it was last identified,’” Dean said. “That’s not how it works.”

The type of telemetry equipment used to track the squirrels dates back decades. Dines brought up an old show — “Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom” — to illustrate the age.

“The main characters in the show would do radio telemetry with essentially the same kind of equipment,” Dines said. “This was back in the ’70s.”

In lieu of any concrete evidence, the professors turned to theory to find the lost squirrels’ locations. Though, after their Rose Garden theory fell through and with minimal evidence to support their hawk theory, they seem to be at an impasse.

Perhaps the collars broke, or maybe the squirrels hopped on the metro to Santa Monica. The squirrels could’ve simply taken a vacation.

Any student who bought into The Sack of Troy’s squirrel misinformation campaign last spring might believe they were euthanized. Of course, they were not, and campus seems to be one of the safest places in L.A. for a squirrel.

We can only hope, for their own sake, that they stayed close by.

The squirrels did not respond to requests for comment.