Hostile architecture isn’t helping anybody

Instead of supporting hostile architecture, governments must support the houseless.

Instead of supporting hostile architecture, governments must support the houseless.

To me, home feels like my mom’s home-cooked chicken noodle soup that warms my heart. Home feels like cozying up in a fuzzy blanket to rewatch one of my favorite movies for the 20th time. It feels like listening to Lana Del Rey on vinyl while reading a book before bed. I am lucky to say that my home feels warm, comfortable and caring.

However, the estimated 75,518 people who experienced homelessness in Los Angeles County in 2023, according to the L.A. Homeless Services Authority, unfortunately, cannot say the same. This is especially considering that rates of unsheltered homelessness rose by 14% from 2022 to 2023, meaning that there are now even more unhoused people struggling while living out on the streets of L.A.

To them, “home” feels like having extremely limited access to, and in some cases, no access to truly nutritious meals. Home feels like days and nights spent outside with little protection from uncomfortable weather like the cold and rain. It feels like constantly checking for potential risks such as badgering from other citizens due to negative stereotyping, theft or the unhygienic conditions of the streets and facilities intended to aid unhoused individuals.

As one woman shared about living as an unhoused person to The Guardian, “If you want the truth, shelters, soup kitchens and other facilities for the poor are the most unsanitary, unhealthy and dangerous places I have ever been.”

Ultimately, it is clear that to people experiencing homelessness, their “home” on the streets doesn’t feel warm, comfortable or caring. And their living situations are only worsened by the rise of hostile, anti-homeless architecture.

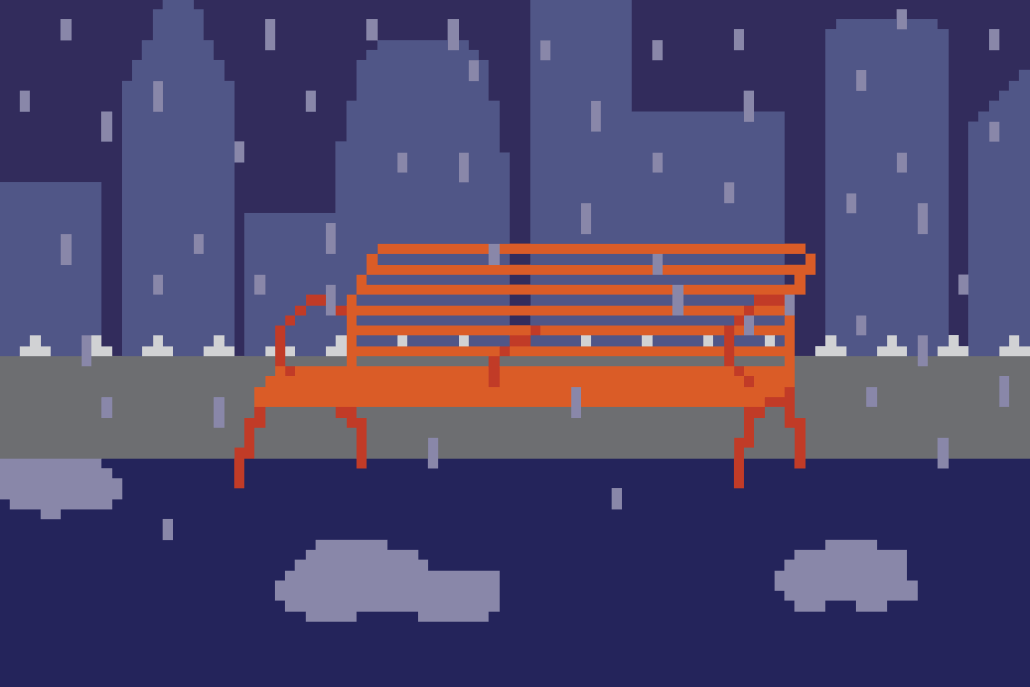

Hostile architecture presents itself in a variety of ways.

According to Rethinking The Future, an organization dedicated to architecture and design, examples of hostile architecture include “metal teeth, bolts separating seating on benches, spikes on railings, metal spikes on lower walls, which perfectly trigger an uncomfortable feeling and an emotion of unfriendliness.”

Additionally, some privately owned places of business and public spaces have implemented high-pitched blaring sound systems specifically intended to “scare away homeless people.” Other spots even set off sprinklers that spray in the night, aiming to ward off the unhoused population in a way LAist has deemed “possibly criminal.”

Cities including L.A. continue to allow hostile architecture to exist in public spaces under pretenses, The New York Times has outlined, of helping to “maintain order, ensure safety and curb unwanted behavior such as loitering, sleeping or skateboarding.”

However, despite seemingly “good” intentions, in effect, hostile architecture lives up to its name: It’s hostile. It promotes a lack of humanity by making the lives of unhoused people even more difficult, and implicitly supports unfounded negative stereotypes that all unhoused people are “dangerous.” In doing so, hostile architecture treats unhoused people more like unwanted nuisances than real people, and as less worthy of living than the rest of us.

While hostile architecture may work to prevent people experiencing homelessness from sleeping or staying in specific spots throughout a city, it still doesn’t address any of the root issues of homelessness, including poverty, racial disparities, lack of access to affordable housing, health issues and domestic violence — as outlined by the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

According to the County of L.A. Homeless Initiative, the most effective way to address root issues of homelessness would be enacting “public policy changes” with goals in mind of increasing access to affordable housing and generating support for people already experiencing homelessness so they can regain stability — financially and otherwise — to exit the cycle of homelessness.

Moreover, beyond hostile architecture undoubtedly not helping the unhoused population, it also seems to be negatively impacting the general public.

Jerold Kayden, a professor at Harvard University with expertise in urban planning, pointed out to The New York Times that, “The irony that some public spaces actively discourage public use should not be lost on anyone.”

His statement emphasizes how hostile architecture makes public spaces less comfortable not just for the “unwanted” populations that they target, but also for all communities that use them.

Considering all this, it is evident that hostile architecture is at best a band-aid solution, and at worst, a growing infestation. Therefore, instead of supporting hostile architecture, government institutions should focus on programs that prevent people from entering homelessness and assist people out of homelessness. Additionally, they should encourage welcoming urban planning decisions so that public spaces can truly be enjoyed by all.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: