Latines must modernize religion

Social progress should be a uniting force for religious Latines — not an obstacle.

La religiosidad latina debe ser modernizada

El progreso social debería ser una fuerza unificadora, no un divisor religioso.

Social progress should be a uniting force for religious Latines — not an obstacle.

El progreso social debería ser una fuerza unificadora, no un divisor religioso.

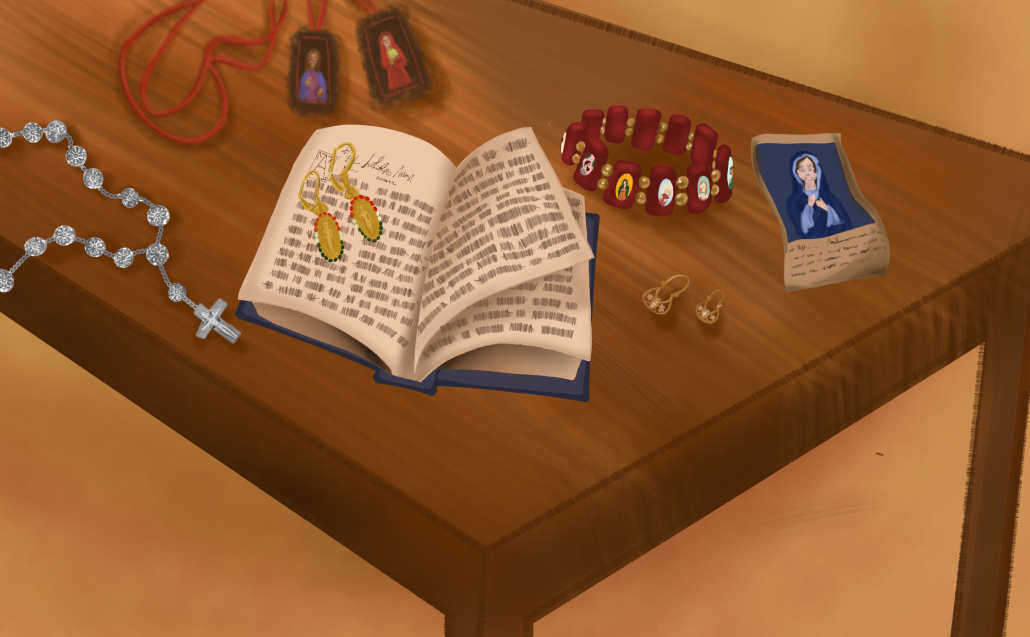

Despite being raised Catholic and even doing my confirmation in México just last summer, I always felt a disconnect with the faith I grew up with. I was never a fan of people telling me to ‘have faith’ when I was in doubt and being met with anger when I would bring up the various horrific moral failings of the Church — the hypocrisy of Catholicism made the religion feel like a farce, and yet I had mixed feelings about abandoning it completely as I became an adult.

Interestingly, I recently had a conversation with a friend who was not Latine nor religious where I recounted my lack of enthusiasm for religion growing up and they asked me, “So why don’t you just remove yourself from religion?”

A valid question, to be fair. But for many Latines, it goes without saying why one can’t just do as they please, especially when religion is involved; I remember when I told my parents a couple years back that I was feeling iffy about being Catholic — that moment felt like a faux pas if there ever was one.

Even though I’d consider my parents to be progressive Catholics, I can understand why they weren’t exactly jazzed about that revelation. According to the Pew Research Center, only 30% of U.S. Latines aren’t religiously affiliated — unsurprisingly, Catholicism sweeps other religions with a 43% majority; meaning, religion is so deeply ingrained in our culture that stepping away from it reads like a personal affront to the values, morals and community that raised you.

Destiny Oquendo, a junior majoring in political science, explained religion’s role within her family, “I think [we] use religion as the common foundation and a lot of friendships build from that — and I also think it plays a large role because it’s generational.” Considering that many Latines have passed down religion for generations, religion-based social lives, norms and expectations are inextricably entwined with daily life.

However, views on religion are quickly changing in the U.S. — even in Latine communities. The Pew Research Center estimates that there has been a 24% decrease in American Latines that identify as Catholic between 2010 and 2022, with younger Latines leading the charge in becoming religiously non-affiliated. My parents, and likely countless other Catholics from older generations, might misinterpret this shift as stemming from a lack of faith, instead of a growing (and warranted) awareness and dissatisfaction with the pitfalls of organized religion.

Anahi Jimenez, a senior majoring in sociology, “I say I’m religious to an extent — I like to practice [Catholicism], but I don’t agree with a lot of the things the Catholic Church does or says.”

Similar to Jimenez, I’m critical of the Church and its actions, but I still wouldn’t consider myself an atheist; I believe in a higher power, pray and do my best to be a good person. But ultimately, Catholicism is just not the right fit for me — as we continue moving into the future, the religion and a sizable amount of its followers have dug their heels into the dirt, begrudgingly inching towards political correctness. Ranging from countless sexual abuse coverups, to permissive attitudes on domestic violence, to hate towards the LGBTQIA+ community and wars on bodily autonomy — Catholcism has inadvertently ousted younger Latines from wanting to engage authentically with the community.

“[Religion] puts everybody in this box — and if you don’t fit in, or if you’re slightly outside of this box, you’re othered or seen as not holy enough.” said Oquendo.

Personally, I have struggled quite a bit trying to understand if and/or where I fit into my community when it comes to religion. I feel loved when I tell my grandma about an ambition I have and she says she’ll pray everyday for my success. I feel cared for when my parents give me the sign of the cross before I head back to L.A. I feel conflicted knowing that there are parts of our religion that bring me happiness, but other parts that seriously make me reconsider my involvement. And unfortunately, it’s not an uncommon feeling as demonstrated by Oquendo and Jimenez.

Even with my personal aversions to Catholicism, I see how imperative it is for understanding and connecting with my family;however, I simultaneously feel that Latines as a community must do better to modernize and meet younger generations halfway in terms of creating and sustaining supportive networks, in and outside of religion. Ultimately, we are all trying to do our best for ourselves and our families and we can’t do so without approaching each other with patience and tenderness.

A pesar de haber sido criada como católica y haberme confirmado en México el verano pasado, siempre me había sentido desconectada de la fe con la que crecí. Nunca fui fanática de que la gente me dijera que ‘debería tener fe’ cuando tenía dudas y que se enojaran cuando hablaba sobre las fallas morales de la Iglesia. La hipocresía del catolicismo me tenía desilusionada, pero no quería abandonar mi religión por completo como adulta.

Recientemente, tuve una plática con una amiga (que no era latina ni religiosa) donde le conté mi experiencia con la religión durante mi adolescencia y me pregunto: “Entonces, ¿por qué no te alejas de la religión?”

Pues … es una pregunta lógica. Pero como sabrán muchos latinos, tradicionalmente uno no puede hacer lo que da la gana, especialmente cuando se trata de religión. Recuerdo cuando le dije a mis padres que tenía dudas sobre ser católica hace un par de años — fue un momento muy incómodo.

Aunque considero que mis padres son católicos progresistas, puedo entender por qué no estaban contentos conmigo después de esa revelación. Según el Pew Research Center, solo 30% de los latinos en Estados Unidos no están afiliados a ninguna religión. Además, el catolicismo representa la mayoría de latinos que son religiosos. Es decir, la religión es tan importante en nuestra cultura, que si te alejas de la religión, se siente como una ofensa personal a los valores, la moral y la comunidad que te criaron.

Destiny Oquendo, estudiante de tercer año de ciencias políticas, explicó la posición de la religión dentro de su familia. Teniendo en cuenta que muchos latinos han heredado la religión de manera generacional, está inextricablemente entrelazada con la vida diaria, la vida social, las normas y las expectativas.

“Creo que [usamos] la religión como base común y muchas amistades se construyen así”, dijo Oquendo. “[La religión] juega una posición importante porque es generacional”.

Sin embargo, las opiniones sobre la religión están cambiando rápidamente en EE. UU. — incluyendo las comunidades latinas. El Pew Research Center estima que ha habido una disminución de 24% en el número de latino-americanos que se identifican como católicos entre 2010 y 2022, incluyendo muchos latinos jóvenes que han dejado atrás las afiliaciones religiosas. Mis padres, y probablemente muchos otros católicos de generaciones anteriores, podrían malinterpretar este cambio como resultado de una falta de fe. Sin embargo, pudiese venir desde un lugar de insatisfacción con las fallas de la religión organizada.

Anahí Jiménez, estudiante de cuarto año de sociología, es parte de este grupo de jóvenes que ha tenido dificultades reconciliando las fallas morales de la Iglesia con sus creencias.

“Digo que soy religiosa hasta cierto punto”, dijo. “Practico [el catolicismo], pero no estoy de acuerdo con muchas de las cosas que la Iglesia Católica hace o dice”.

Como Jiménez, no apoyo las acciones de la Iglesia, pero aun así no me considero atea. Creo en un poder superior, rezo y hago mi mejor esfuerzo para ser una buena persona. Desafortunadamente, el catolicismo simplemente no es la religión para mí. Aunque estamos avanzando hacia el futuro, el catolicismo, y una cantidad considerable de sus seguidores, no ha querido cambiar sus costumbres.

Problemas como innumerables encubrimientos de abusos sexuales, casos de violencia doméstica, odio hacia la comunidad LGBTQIA+ y guerras contra el derecho al aborto, han disuadido a los latinos jóvenes de participar activamente en la comunidad religiosa.

“[La religión] pone a todos en una caja, y si no encajas, o si estás un poco fuera de esta caja, eres diferente o no eres lo suficientemente ‘santo’”, dijo Oquendo.

Personalmente, me ha costado bastante entender si encajo en mi comunidad cuando se trata de religión; siento el amor cuando le cuento a mi abuelita sobre una ambición que tengo y ella dice que orará todos los días por mi éxito. Me siento segura cuando mis padres me hacen la señal de la cruz antes de regresar a la escuela. Me siento en conflicto al saber que hay partes de nuestra religión que me traen felicidad, pero también otras que me hacen reconsiderar seriamente mi participación. Y lamentablemente, no es un sentimiento desconocido o aislado, como lo demuestran Oquendo y Jiménez.

Incluso con mis aversiones personales al catolicismo, veo lo imperativo que es comprender y conectarme con mi familia de esta manera. Al mismo tiempo, siento que los latinos, como comunidad, deben esforzarse más para modernizarse y encontrarse con las generaciones más jóvenes a medio camino en términos de crear y sostener redes de apoyo — dentro y fuera de la religión. Más que nada, todos estamos intentando hacer lo mejor para nosotros y nuestras familias. No podemos hacerlo sin acercarnos los unos a los otros con paciencia y ternura.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: