WALLS OF TROY

No, East Coasters, LA can handle rain. At least, it once could

SoCal and the East Coast handle rain differently, but it’s not just the infrastructure.

SoCal and the East Coast handle rain differently, but it’s not just the infrastructure.

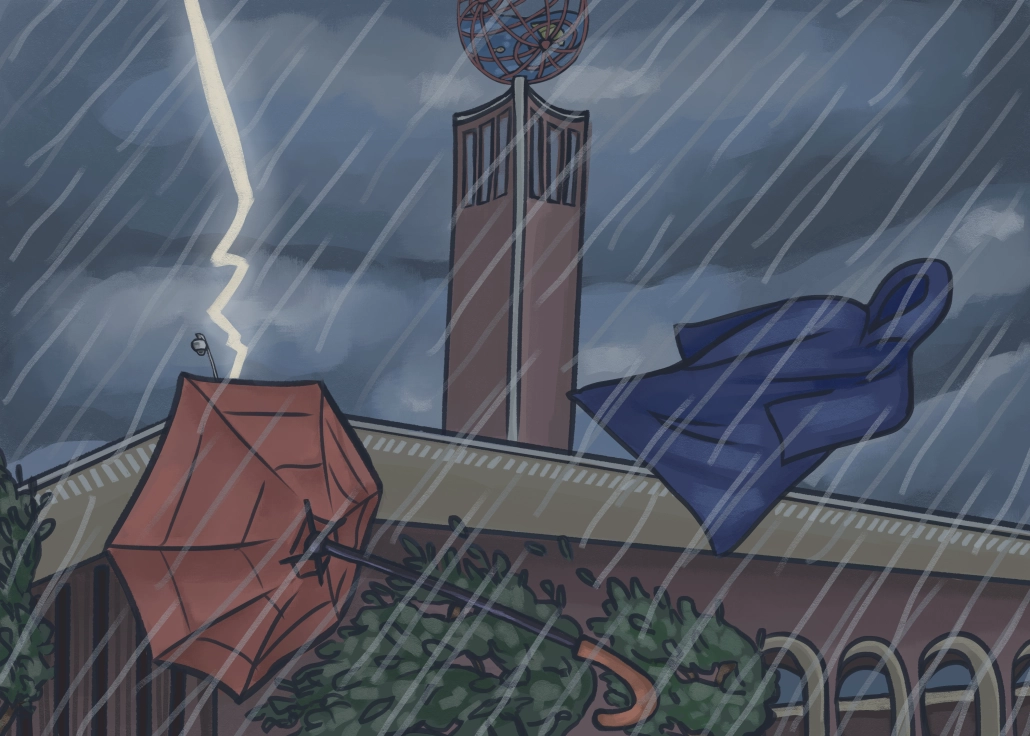

Another rainy weekend has passed. At least for you, dear reader. At the time of writing, I am unfortunately stuck in the shoe-sogging wetland that is Los Angeles after a light downpour. It seems as though L.A.’s infrastructure is entirely reliant on evaporation — Angelenos give great purchase to the curative powers of their ever-present sun.

And, like clockwork, your friends from the East Coast will make a point to remind you that this doesn’t happen over there. That their infrastructure can handle similar levels of rain with ease. That L.A. sucks and is designed poorly. The reality is they’re only kind of correct. Unlike its stormwater, L.A.’s drainage problems go far beyond the surface.

Long ago, when L.A. was a pristine wilderness coexisting harmoniously with its indigenous inhabitants, flooding was a natural part of the annual climatic cycle. The L.A. River, a majestic waterway, would overflow with rainwater during the winter months. As the water flowed, it would slowly seep into the dry Earth, replenishing stores of groundwater and nourishing the environment. The rest would drain into the ocean or evaporate.

Settlers arriving en masse at the turn of the century encountered this phenomenon and felt it was a great idea to build as close as possible to this raging force of nature. To their great surprise, their homes were inundated and their livelihoods were destroyed by the flooding river.

These settlers, being stubborn or foolhardy, felt the best course of action was to continue building by the river. So the city stepped in and turned the L.A. River, nature’s solution to the L.A. rains, into a concrete channel.

Nowadays, that surface water gets channeled into the sewer system where it moves sewage and is unceremoniously dumped into the ocean. Of course, not being allowed to drain into the soil as it once did, this water also pools in flat areas until the janitorial sun comes around to mop it up.

But what your East Coast friends may not know is their own rivers have been artificially altered to divert drainage. For instance, as the city of Boston began running out of room for further development around 1900, streams supplying the river were culverted — in other words, covered up — so humanity could expand over them.

The difference between culverting and channelization is that, in culverts, these feeders into the watershed are still preserved; as long as stormwater flows into these covered streams, water can reenter the natural environment. It’s just not as accessible to the surface. Channels prevent this water recycling, parching the land.

Then why did L.A. not use culverts? One answer: geology. The L.A. Basin is built upon dry sandstone, whereas the East Coast is founded on somewhat rockier, more moist sediment. Crucially, dry sediment has an overall lower capability of liquid absorption, meaning on drier soil, water will have to travel further before being absorbed. In soil with a balanced moisture content, water will be absorbed much better.

The fact that L.A.’s rain comes in bursts only exacerbates the problem; large amounts of rainfall for short durations are even harder to absorb.

That is why water must travel along the surface — causing floods — in L.A., while on the East Coast, it drains more easily into rivers. Water is not absorbed quickly enough by the soil to prevent percolation. The East Coast handles rain better because it rains more, in short. In addition, 61% of L.A. is covered with impervious pavement.

And this problem of absorption can be readily seen here at USC. McCarthy Quad flooded during February’s record downpours, and because the water did not drain quickly enough, the grass was torn up during the preparation for an event. Now drainage — on a grass field, mind you — is being installed to divert the water that would otherwise just sit there, according to statements from USC Facilities and Planning Management.

So yes, L.A. has problems, but that’s because the weather is relative. The East Coast will be experiencing flooding as climate change fuels ever more intense storms, and these once-stable rivers will begin to overflow. By 2070, the Charles River will flood over 3,000 acres that do not currently experience inundation due to these more powerful storms.

It’s not that L.A. can’t handle rain, it was handed a different deck of cards. It’s like saying the East Coast can’t handle great changes in elevation. It just doesn’t happen over there.

Climate change is affecting all of us. It’s not just an L.A. problem. It’s everyone’s problem.

Daniel Pons is a sophomore majoring in geodesign writing about USC’s architecture and how it impacts the community. His column, “Walls of Troy,” runs every other Monday.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: