WALLS OF TROY

Folt’s campus is changing, and students are left behind

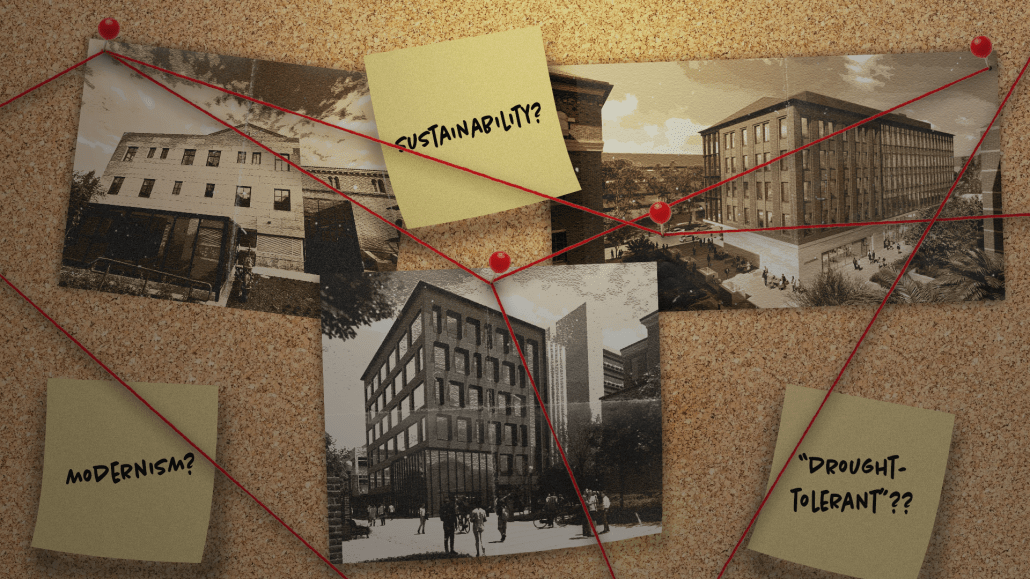

Despite the University’s growth since major scandals, many students feel that it’s abandoning an essential part of its architectural identity.

Despite the University’s growth since major scandals, many students feel that it’s abandoning an essential part of its architectural identity.

The new buildings

As we are all almost painfully aware, USC is hell-bent on pushing its sustainability prerogative. Banners celebrating Earth Month are plastered across Trousdale Parkway, and we are constantly reminded of the various waste-reducing and water-saving measures implemented throughout campus. Every available square inch is seemingly dedicated to the advertisement of sustainability.

The greatest billboards, however, have to be the newest buildings on campus.

The School of Dramatic Arts extension and in-progress Ginsburg Hall are shrines to sustainability, clad in heat-deflecting terracotta and endless curtain walls of glistening insulated glass. They are sleek, clean and progressive — and students seem to hate them.

‘Actually nauseating’

A Spring 2024 Daily Trojan survey asked for student opinions on various buildings constructed throughout USC’s history, and it received 85 responses. Once tallied, the results were clear: Of the buildings on University Park Campus, respondents liked the ones built under President Carol Folt’s tenure the least.

Rather ironically, the buildings students most preferred — aside from the original 1920s Romanesque staples of campus — were those of the most recent era of construction under former President C.L. Max Nikias. For every student who described a Nikias building as “slay” on the form, there was one who wrote “wtf is this” describing a Folt structure.

So, why did Folt even stray from an already successful formula? Jon Soffa, University architect, explained that part of the difference in aesthetics is a political move on the part of Folt.

“Our current administration is probably more aggressive in distinguishing itself from other administrations than the prior two, especially through sustainable and progressive policy,” Soffa said in an interview with the Daily Trojan.

An element of that differentiation, he said, is how sustainability is emphasized through architecture.

“If you walk by Ginsburg, where you’ve got, obviously, a lot more glass area to skin [opaque material] ratio,” Soffa said. “If you’re aware, and most people are these days, [you] would notice that [this] building is different than many others on campus.”

Hunter Gaines, executive director of capital construction development UPC, also noted that the enormous amount of glass could serve to advertise the innovation occurring within the building.

“I would assume that that glass facade, with public areas [visible], [would serve as] a way to invite people into the building,” Gaines said.

But as seen through renders, the best views into Ginsburg Hall are across the street in a parking garage. The building, almost poetically, turns its back to the students who would most appreciate it. What’s telling is that the publicly available concept art for the hall is elevated, hiding the fact that, on the student level, it appears as a blocky monolith. A commuter driving past would have a better view than the student going there for class.

Students gave Ginsburg Hall a median rating of three out of five possible points.

But the SDA extension fared far worse, as students rated it a paltry median one of five possible points. Respondents called the project everything from a “Minecraft building block” to “actually nauseating,” many of whom lamented that it did not match the aesthetic of the original church.

Rather surprisingly, restoration codes mandate the contrast.

“The addition has a completely different look. But that kind of follows the Secretary of the Interior’s standard for historic buildings. They don’t recommend that you try to make the addition look like the original building,” Gaines said.

I do want to add that Capital Construction Development did a phenomenal job maintaining the character and beauty of the original church. The facade, with all of its intricate brickwork and moldings, is just about unchanged, aside from a window or two.

But the SDA project does not get off entirely scot-free, as the extension still reads like tumorous outgrowth of terracotta from an otherwise beautiful building. While regulations recommend that it be different from the original building, there were other designs that were scrapped in the approval process for this project.

President Folt’s influence

These preliminary designs never saw the light of day, and remain .jpg files in the hard drive of some architect’s office. I cannot say for certain whether students would have preferred those designs, but they were discarded in part due to the direction of one President Carol Folt.

Before I go on, I do want to note that every USC project is overseen by an incredible number of individuals working to have the final product be a viable and long-lasting asset to the University. That said, I found it fascinating that Folt, perhaps the figurehead of the sustainability movement at USC, plays a non-insignificant role in the look of campus.

“My boss basically reviews each project with [Folt] and goes through the major features … [My boss] shows [her] options and sometimes answers questions about those [options],” Soffa said. “But typically, the President likes to see options and we present her with options.”

In essence, Folt is given a set of designs for these new projects and decides which one best fits her vision for campus, presumably one centered around sustainability. Given the precedent set by previous administrations, the architecture chosen could have been something more traditionally “romanesque,” as seen in many developments during Steven B. Sample’s tenure as president.

The move toward modern architecture is a deliberate one, symbolizing sustainability through design and executed under the influence of Folt’s predilection. To her credit, though, the University’s relentless push toward sustainability has made genuine headway.

Initially appointed to help USC move past scandals, Folt’s USC has moved away from the “University of Spoiled Children” to the “University of Sustainable Culture.” Drought-tolerant landscaping is slowly taking over campus, solar panels are being installed atop older buildings and the Sustainability Hub has a major, even symbolic, presence at the literal heart of campus.

USC has need-blind admissions, and 68% of the student body receives some kind of financial aid. USC is looking to shift in a more modern, forward-looking direction. The buildings erected under the current president directly reflect this shift in their outward aesthetics, retaining bricks — or at least their memory — while presenting themselves as sleek, modern, novel and sustainable.

Before Folt’s tenure

Folt is not the only president to use architecture as a tool for communication. Just seven years ago, Nikias christened USC Village with the statement “the looks of the University Village give us 1,000 years of history we don’t have.” His goal was to make USC a more prestigious university, so he appropriated collegiate gothic architecture and all of the repute associated with the style.

The current set of buildings is doing the same thing the University has always done: build in reflection to what it wants to advertise.

But for the first time in arguably 30 years, the University is no longer building for students. Sample revived the romanesque of the University’s historic core, while Nikias injected collegiate gothic into USC’s architectural playbook to resounding praise from students. People like those buildings. They may not be for everyone, granted, but the resounding majority of students enjoy the architecture.

Conversely, the resounding majority of students feel negatively about USC’s newest developments.

What could be

When I shared the survey results with Soffa and Gaines, they both expressed surprise and intrigue. Soffa clarified that the final product of any building is the result of a diverse range of opinions, some of which may not be in complete agreement over the final result.

“The goal of the University, it’s … [to] reflect whatever the current and future ambition of the programs that the buildings serve,” Soffa said. “The input on those [buildings] is certainly diverse … I’m sure not everyone is of the same opinion.”

Gaines said he felt that there was more that could be done for students given the results of the survey.

If anything was to be gathered from the survey results, it would be that students dislike blocky buildings. This fact extends across all building eras. Unfortunately, in the present architectural sphere, sustainable means modern, and modern means blocky. It’s a connotational cycle in which we seem to be trapped.

It’s one also reinforced by the skyrocketing land prices around USC and Los Angeles, forcing new construction to take up as much of a rectangular footprint as possible. Ultimately, the current forces surrounding construction at USC are conspiring toward the blocky prisms springing up around campus.

But that need not be the case. As demonstrated throughout USC’s history, its architecture is reactionary, molded by the demands and pressures of the political and cultural climate. Sustainability needn’t be boxy, nor should we move away from it.

USC is a beautiful university — it’s one of the reasons I came here. Something about the old campus just feels perfect. I think other students here feel that, too.

USC can and should be sustainable. But on the path to sustainability, it lost a bit of its heart. It just needs to remember that students want to be around a beautiful campus. We still like to feel a little spoiled.

Daniel Pons is a sophomore majoring in geodesign writing about USC’s architecture and how it impacts the community. His column, “Walls of Troy,” runs every other Monday.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: