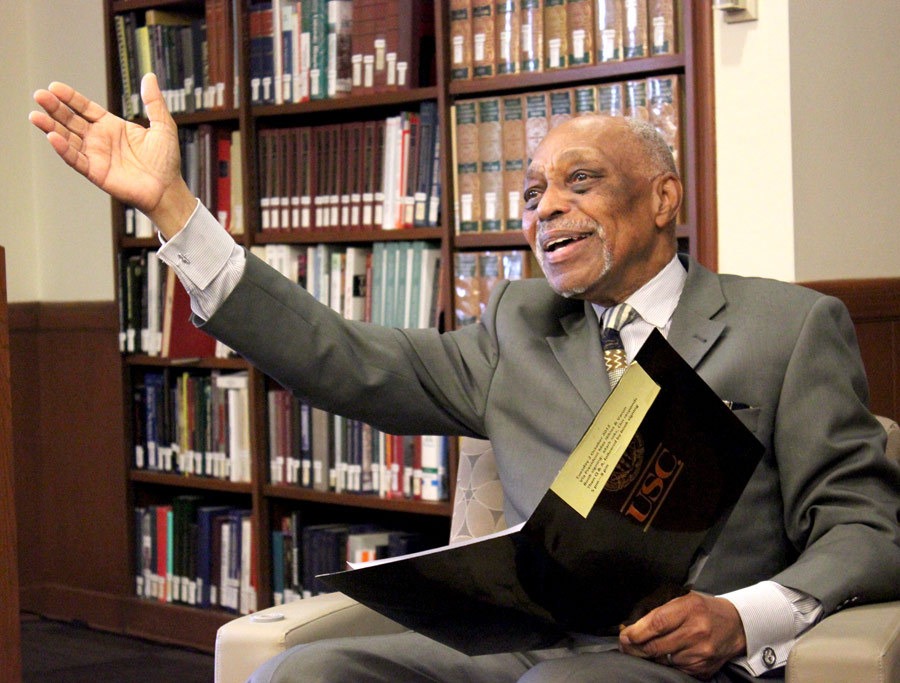

Friends reflect on Cecil Murray’s legacy

University leaders remember the late reverend’s impact on USC students and staff.

University leaders remember the late reverend’s impact on USC students and staff.

The Rev. Cecil “Chip” Murray — a prominent activist, a pastor and the creator of USC’s Cecil Murray Center for Community Engagement — passed away April 5. Those who worked with him at USC remember him for his determination to uplift and support low-income Angelenos, as well as his approachability, humbleness and wisdom.

Dean of Religious Life Varun Soni said Murray’s service to the community went far beyond his sermons. Murray ran a job creation center, did gang intervention work, funded early childhood development schools and permitted the AIDS Healthcare Foundation to offer free HIV screening services at his church on Sundays.

“[Murray] took that idea that the church should be doing work outside of the church walls,” Soni said. “He was preaching with his feet; he was in the world. He wanted to bring that to USC … He believed that both the church and the University needed to be in the world of their communities.”

While Murray did not teach his own class at USC, Soni would bring him in yearly to “Global Religions in Los Angeles” to have Murray give a lecture on the Black church. Rather than providing purely academic content, Murray often delivered a speech closer to a sermon, leaving a profound impact on students.

“Students were in tears. They knew they were in the presence of greatness. They knew it. They could feel it. Even if they weren’t Christian, even if they never heard a sermon before, they could feel their spirit was moved. In my teacher evaluations, no one ever says anything good about me, but everyone says beautiful things about Chip,” Soni said.

Murray served as a pastor of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church of L.A. for 27 years. His time in this role coincided with the L.A. Riots of 1992. His church sheltered 125 people on the first day of the riots and advised President George Bush, Gov. Pete Wilson, and Mayor Tom Bradley on how to contain and subdue the violence. After the riots passed, he helped raise over $400 million for low-income communities in L.A.

Donald Miller, a professor of religion who founded the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture, first brought Murray to USC for his integrity, leadership skills, charisma and his selflessness toward others. He said Murray’s activism during these riots was his first introduction to the pastor and his work and that he was further drawn to Murray because of his selflessness.

Miller recalled that Murray survived a plane crash while in the Air Force. Murray survived, but the pilot did not, which prompted Murray to dedicate his life to serving others.

“[Murray] always said from that point on, he was living for two people, not just for himself,” Miller said. “I really think that was an attitude he always had: that life was only worth living if you’re living for others.”

When Murray arrived at USC in 2004, he helped found the Passing the Mantle program, which would eventually become the Murray Center. In these programs, Murray mentored pastors on how to best serve their communities beyond simply giving a good sermon. He taught them how to set up nonprofit organizations, engage with other houses of worship and connect with community organizations.

The Rev. Najuma Smith was a member of Passing the Mantle’s inaugural class and said the program taught her how important community engagement was.

“[Passing the Mantle] helped to solidify that faith and community and civic engagement go hand in hand,” Smith said. “Our faith work is really lived out and expressed in the work that we do in our communities, whether it’s civic or community engagement.”

Smith described Murray as a man who was disciplined and funny, punctual and humble, and understood how to give people his wisdom rather than his opinions. She also said Murray never acted arrogant but was a “reachable” man who everyone felt connected with.

“Everybody felt like he was theirs or that they were his. Everybody felt like a daughter or a son … Everybody got dignity and respect. Everybody was treated with love and honor,” Smith said. “He was just a person of courage … We were more afraid of him going than he was.”

Soni said future generations of USC students would look back on Murray as an iconic civil rights leader. He said students would think about how Murray once worked at USC in the same way that Princeton University students marvel that Einstein once taught there.

“I want people to really know that [Murray’s] presence on our campus is an example of blessing and inspiration all around us; we just have to look for it,” Soni said. “There are people around us who actually walk the walk and don’t just talk the talk, and if we just have the right lens to see the world, we’ll see it everywhere.”

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: