Alone and searching for meaning: Inside USC’s ‘high-pressure group’ problem

Amid a crisis of loneliness, some religious clubs offer more than spiritual guidance. Vulnerable students are paying the price.

Amid a crisis of loneliness, some religious clubs offer more than spiritual guidance. Vulnerable students are paying the price.

The first week of class at USC barrels down at you with the speed of a Metro train.

Trousdale Parkway, the campus’s superhighway of e-scooters, bikes and skateboards, is a flurry of students whipping by to get to their next lecture. Groups of friends swarm around Tommy Trojan, dissecting new living situations, new teaching assistants, new clubs.

The isolation of an unfamiliar environment can be overwhelming.

Then, in a moment of clarity, you hear a voice call out: “How are you?” Someone who looks like a student asks if you need help finding a class or if you just want to talk.

But the conversation soon shifts to heavy, existential questions: “What do you think happens when you die?” “How well do you know your faith?” Then, finally, they ask if you’d care to attend a Bible study, and they want to exchange phone numbers.

Religious proselytizers have a constant presence on campus. Though not all are recognized by the University, they invite students to Bible study, promising a devoted faith community unlike anything they’ve experienced before.

Last spring, the Daily Trojan spoke with 18 people who have experience with these organizations, ranging from brief run-ins to yearslong involvement. Some dove deep and connected with their faith in entirely new ways, while others plunged into communities where they felt trapped, deceived and helpless.

‘An off feeling’: Some students uneasy with recruitment tactics

For many students, brushes with “high-pressure” religious groups on campus — defined by their aggressive recruitment tactics and the exertion of control — are much more casual, everyday occurrences: a quick chat outside the USC Bookstore; an awkward wave of, “I’m not interested!” from the Physical Education Building’s steps.

But some say they’ve been approached more times than they can count, or pursued so much it made them uncomfortable.

Tyler Truss, a sophomore majoring in accounting, said she was routinely asked to attend Bible studies throughout her freshman year. She’s had most of her run-ins with The Harvest, one of the most prolific Christian groups at USC.

“The group will spot me, and they’ll be like, ‘Hey, I talked to you. When are you going to come?’ and it’s just very annoying,” said Truss, who is religious. She said she felt pressured into giving her number to one of the proselytizers.

The University has more than 40 recognized Christian student organizations, but The Harvest — which now goes by D.R.E.A.M. Campus Ministry @ USC — isn’t one of them.

Though she’s told the group she isn’t interested, Truss said she receives texts “consistently” imploring her to come out to one of The Harvest’s worship events. Changing her route to avoid interacting with the group’s members is now ingrained in her routine.

The same goes for Sarah Anderson, a sophomore majoring in architecture, who said she was approached three times during her first week on campus.

“I was looking for a Bible study group,” Anderson said. “I did give the girl my phone number, and I had to block her because she harasses me on the phone.”

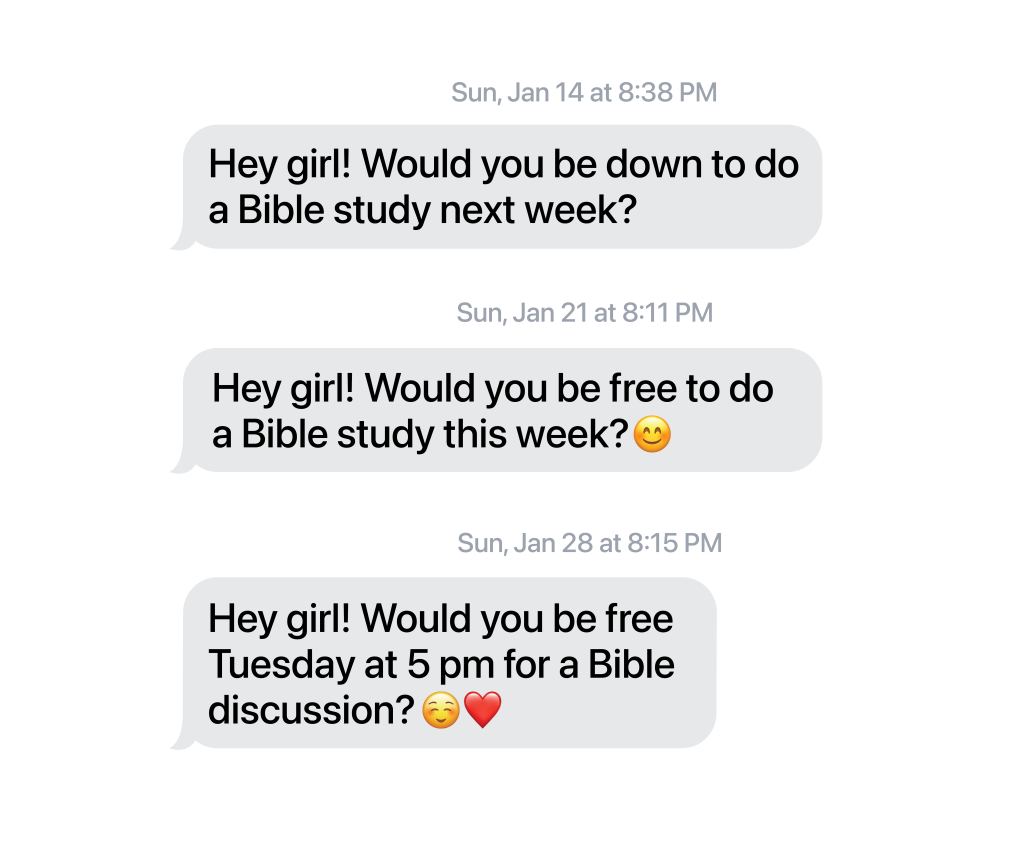

From the first week of Spring 2024, a member of The Harvest texted Anderson roughly once a week asking if she was interested in attending a Bible study. The messages continued for two months.

As a spring admit, Anderson said it was a challenge to find a faith-based club she connected with right off the bat. Though she considered meeting The Harvest for one of its Bible studies outside the USC Village Starbucks, older students at the USC-run Caruso Catholic Center told her the group wasn’t University-approved.

“I’ve been religious my whole life, and this one experience gave me an off feeling,” Anderson said.

The Harvest, similar groups banned by some colleges

In August of 2022, The Harvest set up a table at USC’s Involvement Fair with index cards displaying various Bible trivia questions, a bowl of candy and a tri-fold poster board with information about the club, including its values — one sentence typed out onto a piece of paper: “We believe in the Bible, living by what it says, and spreading the Good News to others!”

The table marked the start of another semester on campus as a recognized organization. The Harvest continued searching campus for new people to invite to small-scale Bible studies and weekly church services at Taper Hall. They baptized more and more people in the fountain by the Traveler statue.

The Harvest is a branch of the International Christian Church, a nondenominational Christian church with nearly 12,000 members operating in 43 states and 55 countries. The organization heavily emphasizes recruiting new members and growing the church in a practice called “discipling.”

College branches of the ICC have sprouted up over the past few decades, attracting negative attention for their aggressive recruitment tactics. Its incarnations have been burned with the “cult” label on some campuses.

On its website, USC’s Office of Religious and Spiritual Life defines high-pressure religious groups based on nine characteristics, including manipulative recruitment, high commitment and claiming to have an “exclusive understanding of the truth.”

The Harvest, which currently counts 11 members, had good standing in the years leading up to the coronavirus pandemic, but Dean of Religious Life Varun Soni said the organization’s recruitment efforts ramped up following students’ return to campus.

Although many religious groups employ missionaries or proselytization, Soni said he’s never seen a group operate with the “high-pressure tactics” The Harvest uses in 15 years at USC.

In April of 2023, ORSL revoked the organization’s recognition. In an email to The Harvest’s leaders and members, Soni cited irreconcilable differences between ICC’s practices and ORSL’s Ethical Framework, a standard that the University holds all recognized religious student organizations to.

The email alleged that ICC uses “aggressive proselytization” tactics, pressures students to prioritize religious commitments over academics, and assigns “handlers” to students who encourage them to dissociate from family and friends.

Revoking The Harvest’s recognition meant it could no longer request University funding or table on campus. The decision also prevents the group from reserving USC facilities for its weekly church services, which used to fill large lecture rooms in Taper Hall.

Olayinka Oredola, a co-leader of the ICC region which The Harvest falls under, disputed the allegations Soni and ORSL made in the email. Oredola said USC is punishing practices critical to living out one’s life as a Christian and that allegations of “high-pressure” tactics are exaggerated.

“They sent myself and all the students and my wife an email saying, ‘Hey, we revoked [your recognition]. You guys are done,’” Oredola said. “I just told them, ‘Well, I’ll see you around campus. We’re still going to be here.'”

The Harvest persists despite loss of recognition

Members of The Harvest told the Daily Trojan they joined the group because it taught them how to follow the Bible and apply it to their lives, unlike other Christian organizations on campus.

Tre’ Baker, a junior majoring in cognitive science and a member of The Harvest, said applying the Bible to his life involves proselytizing, a practice he said mirrors the first-century church Jesus established.

On average, Baker estimated that he approaches at least 30 people every day. What might come off as harassment is The Harvest’s members’ attempt to share their faith with those who need it, he said.

“The Bible says in Acts 17 that God appoints the times and places for people to meet,” Baker said. “Someone could have had a near-death experience, maybe they got broken up with, maybe someone in their family died, maybe something catastrophic happened in their life — and now they actually want to do a Bible study.”

Several members of The Harvest, including two of the Harvest’s leaders, joined the ICC after being approached at their college.

Members of The Harvest also have spiritual mentors, but Oredola said the mentors are more like “accountability” partners than “handlers.” He said the goal of these relationships is to keep people on the right path and hold them accountable for following their faith, though he said mentees ultimately have free will.

“It’s not this one-way street, like, ‘I’m going to talk down to you, I’m going to tell you what to do,’ but it’s iron sharpening iron,” said Regine Oredola, who leads the ICC region overseeing The Harvest alongside her husband. “What’s really cool is, at any point, if there’s a disagreement, we do have the same standard, which is the Bible.”

The Rev. Joe Kim, director of campus ministry at the Caruso Catholic Center, said The Harvest’s members have used the Catholic Center to gain legitimacy.

Kim said he and other regular visitors of the Catholic Center have noticed members of The Harvest outside the center talking to students or attempting to use its facilities without permission.

The Harvest and the Catholic Center share similar messages about following God, reading the Bible and strengthening their faith, making it difficult for students to distinguish between the two, he said.

“Let’s say a student has a bad interaction. They just make that association: ‘Well, since the content of what they’ve been saying, with the similar terms, happened here on the grounds of the [Catholic] church, it must be the Catholics who are trying to do this,'” Kim said. “I find it very disturbing and disrespectful, but really a big disservice.”

Attention, care in a time of ‘spiritual crisis’

Though college campuses lifted pandemic-induced isolation and social distancing restrictions more than two years ago, the weight of loneliness and detachment continues to plague students, Soni said.

“The real spiritual crisis of our campus is loneliness, and I see that getting worse every year,” Soni said. “Religious community can be a remedy for the kind of loneliness that students often face when they come to a campus as big as USC.”

And as religious participation has risen across the board since the coronavirus pandemic, high-pressure groups’ success at USC has only grown, Soni said. To gain a sense of belonging, students can become vulnerable to the persistence and “love-bombing” tactics of groups that promise attention, connection and meaning.

“That love is actually manipulated into blame, shame, guilt and a power that allows these groups to micromanage a student’s life,” Soni said.

For students who feel targeted by high-pressure groups, Soni said the University can issue a temporary “stay away” order. The Department of Public Safety and the University’s Office of Threat Assessment and Management are also available to students facing harassment from high-pressure groups, Soni said. But USC can’t ban them from public areas like Trousdale and USC Village because their members have First Amendment rights.

Although The Harvest is one of the most visible groups that uses controversial practices on campus — leading to its loss of University recognition — it isn’t the only one.

University-recognized group also exerts pressure, former member says

On her way to dinner one night, then-freshman Melanie Li paused at a table set up on campus to get some free boba. After a quick exchange, the posted-up group invited her to a Bible study. Little did Li know, she would be a part of that group for the next five years — and come to regret it all.

The group was Acts2Fellowship, and the year was 2015. A2F, a recognized student organization, is an arm of Gracepoint Ministries, a widespread network of campus churches.

Soon after that first encounter, Li, who preferred a pseudonym be used for fear of retaliation, started showing up at the group’s Friday Bible studies. Raised culturally but not strictly Christian, she came in with little religious background and was what some call a “seeker”: She tried out several Christian groups and wasn’t, from the get-go, a regular at any of them.

Over time, she became more and more committed to A2F. She went to Sunday services and retreats and took courses in “Christian foundations.” At the time, the group would host worship events at King Hall, Taper Hall and the Religious Center.

A few months in, Li’s mentor, or “spiritual leader,” started to pressure her — including discouraging her from living with certain friends her sophomore year and pushing her to quit the marching band.

Those pressures were often prefaced by intense displays of care that amounted to “love-bombing,” Li said.

“I received a lot of attention and a lot of love,” she said. “That was a way that they would pressure me to attend events or to do certain things or to make certain decisions about my life.”

One of A2F’s key virtues, from Li’s perspective, was a deep tie between members’ self-perception and the group: “Your identity is your ministry.” Surrounded by a community of the only friends she’d kept at USC, Li stayed in the group past her college years as a mentor.

After five years, a switch clicked for Li. Despite putting in 30 hours a week to recruit international students into the church while working her post-graduate job, she said she was repeatedly told she wasn’t spiritual or devoted enough. So she left.

“The more that I found my identity within the group,” Li said, “the harder it was to leave, and the easier it was for them to gaslight me into thinking certain things about myself.”

Members who left the church were cut out and disregarded, Li said. When she began to resent and rebel against the group’s control, Li feared being ostracized the same way.

Other former members of Acts 2 college churches across the country allege “spiritual abuse,” characterized by a coercive environment and leaders that sought to control members’ personal lives.

Though Li graduated in 2019, another student who joined A2F in January 2022 told the Daily Trojan she also faced incursions into her personal life. When the student, now pursuing a master’s degree at USC, started raising concerns about the group’s behavior, she said she was “shunned” and pressured to leave.

Despite these testimonies of “high-pressure” tactics, A2F is a recognized, funded student organization at USC with roughly 40 members.

The group’s most recent president, Burabari Yorka, said she sees no issues with A2F’s practices.

Yorka, a senior majoring in health promotion and disease prevention studies, joined A2F with her sister their first week on campus. She hadn’t tried out any other Christian groups when an A2F member invited her to a Bible study after a brief conversation at the dining hall, and she hasn’t looked back since.

“Everyone was very welcoming, and they really truly cared about how you’re doing,” Yorka said. “Especially being new to campus, that just really touched me and my sister.”

Now, Yorka spends her Fridays and Sundays with the club, which she said has helped her develop a deeper connection with Christianity and other students.

A2F prioritizes “relationship over religion,” Yorka said, but doesn’t ask members to make unreasonable sacrifices for the group. She also doesn’t think anything A2F does can be classified as “high-pressure.”

“It’s all a personal choice,” Yorka said. “No one’s ever forced me to do anything.”

Students find joy, pain in searching for a faith community

“From Luke 14, God said, if you want to be a Christian, you must give up everything,” Olayinka Oredola said. Sacrifice is a central component of The Harvest’s vision of a life based in the Bible, but the church leader said sacrifice comes out of free will, not pressure.

For one student, that meant giving up a full-ride scholarship at USC.

The student had joined the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps on campus after earning a scholarship in exchange for military career placement. One of his NROTC friends — Ian Williams, a senior majoring in economics and mathematics — said he knew something was wrong when the student missed the group’s mandatory Fall Ball last November to attend The Harvest’s church service. By the end of the semester, the student had walked away from the program and scholarship.

That student was Ranier Velasco, and he said the decision was worth it.

A year before he joined The Harvest, Velasco was a high school senior, unsure where his life would lead. Having grown up Catholic, Velasco heard the stories of David and Goliath and Jesus on the Cross but said nobody had taught him the Bible’s true meaning.

He searched for answers to life’s mysteries in the works of Jordan Peterson, Marcus Aurelius and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Velasco said the books helped him understand how to go through life but failed to answer the question: What is it all for?

Then, last September, a member of The Harvest reached out to him; it was Velasco’s second month at USC as a freshman majoring in health and human sciences.

Now a member of The Harvest, Velasco said he was grateful that the group taught him to live “how Jesus lived” and helped him grow in his faith. But Williams sees his former friend as just one of many students who have had run-ins with The Harvest, and one of the few who were manipulated to stay.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: