DOWNLOADABLE CONTENT

Interactive media is high art’s summit

Film, music and theater are highly esteemed in the critical and creative worlds, so why aren’t games?

Film, music and theater are highly esteemed in the critical and creative worlds, so why aren’t games?

Those who have known me for a while know that I’m not the best at hiding my latent pretensions when it comes to the topics of art and philosophy. I was originally accepted into USC as a philosophy major and aspired to become an archaeologist. I cry when I visit museums — I apologize to the tourists who witnessed my open weeping at the Uffizi Gallery — and enjoy casually analyzing literature, cinema and art with my friends. I know I sound insufferable, but please save your boos of disapproval for the end of the article.

I only write this introduction to communicate a crude familiarity with the intersection of art and philosophy — or rather, the existence of an exclusive club many academics (those far more annoying than me) have coined “high art.” For many, this clique of artistic work only allows members from the following seven categories to join: painting, sculpture, architecture, literature, cinema, performance and music.

If you have your critical-thinking cap on, you’ve already spotted something evidently missing from that list of worthy art forms — interactive media. Numerous academics and critics still exclude video games from their classification of high art. Honestly, this should not be surprising, due to the relentless negative press and hate campaigns waged against games that began haunting the medium in the 1980s. Granted, this media panic spanned far more than just interactive media — think “Satanic Panic” — but it only stuck to games past Y2K.

Though some would claim otherwise, interactive media is far from a nascent art form. Arguably, the first game was made in 1958 by a nuclear physicist who helped J. Robert Oppenheimer in his quest to develop a nuclear warhead. Since then, video games have only continued to rocket forward, propelled by advancements in technology, art and storytelling.

As early as the 1980s, some began to notice the artistic potential of interactive media. Titles such as “Moondust” (1983), “EarthBound” (1994), “Baldur’s Gate” (1998) and “The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time” (1998) enraptured players with more than just mechanics meant to entertain — clearly, the games were trying to say something through their narrative, art and music.

The use of a term such as high art implies a binary, or rather, the existence of “low art.” This is my main issue with such an approach to art appreciation and analysis. Critics and academics view interactive media as low art as they reside on a pedestal, forced to look down their noses to even see the medium.

Video games have always been on the periphery of critics — never directly in their line of sight — because they turn their heads away from games every time they enter their vision. If you navigate to the websites of any publications with respected arts & entertainment criticism such as The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, most of the time you won’t find a games tab on the front page. Many of those uneducated about the artistic potential of video games only think of games as mind-numbing pastimes rather than Metropolitan Museum-worthy artworks.

It is human nature to categorize things. I can tell you my star sign and Myers-Briggs quicker than my blood type (Pisces, ENTP). I do not hate the existence of high art categorization, I simply disagree with the way art is classified as such. Limiting high art to the aforementioned seven art forms not only restricts the evolution of art as a concept but also locks deserving artworks out of critical and academic recognition. Sure, art is entirely subjective and high art is in the eye of the viewer, but I would like to see interactive media receiving formal critical recognition from the art world.

To me, games are a pinnacle of artistic expression and evolution. They marry many pillars of art, as film does, but have the advantage of viewer interaction, which opens countless doors that remain shut for other mediums. Music, visual art, literature, cinema and performance are all arguably facets that contribute to the creation of a game. Between score, dialogue, acting, cutscenes and other factors, games are the ultimate amalgamations of artistic potential.

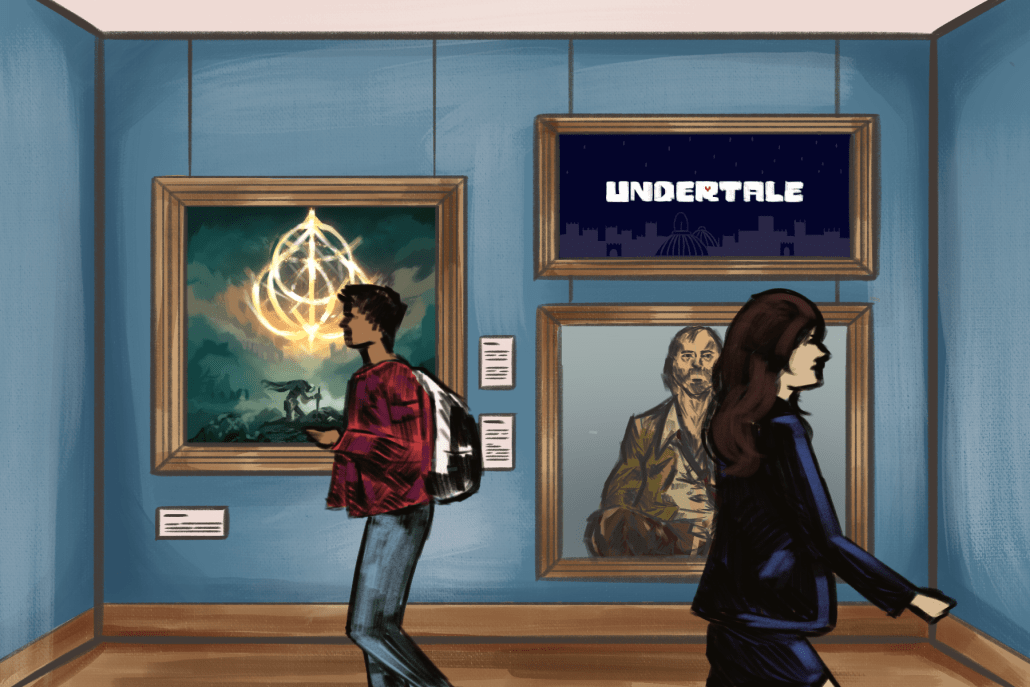

Not every game is high art. Again, since art is subjective, I can’t objectively say what is and isn’t high art — that is for you to decide. But, titles such as “Disco Elysium” (2019), “Elden Ring” (2022) and “Outer Wilds” (2019) would be my personal picks to kick off a new era of interactive high art analysis. Each of these titles blew me away with their art, scores, gameplay and narrative, and I am certain if an art critic got their hands on one, they would agree.

Aubrie Cole is a junior writing about video games in her column, “Downloadable Content,” which runs every other Tuesday. She is also an arts & entertainment editor at the Daily Trojan.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: