The franchise era will inevitably come to an end

Counter-culture will lead us out of entertainment’s infinite nostalgia purgatory.

Counter-culture will lead us out of entertainment’s infinite nostalgia purgatory.

I am afraid to admit I have been ceaselessly binging “Friends” for the past few weeks. As bedtime approaches, this is precisely the comedy I need to turn my brain off — and I would be lying if I said that it didn’t give me a much-needed dose of familiarity as the academic year and its courses, assignments and extracurricular commitments start to mount.

Yet, I hate canned laughter; I don’t really like the characters and I automatically despise the taste of anyone unironically preferring the show’s dumbed-down comedy over more sophisticated classic sitcom offerings like “Seinfeld.”

This past week, Max updated the show’s assets to celebrate its 30th anniversary — a big deal in the corporate world. In the past decade, franchises based around intellectual property have become a key part of most major entertainment corporations’ strategies.

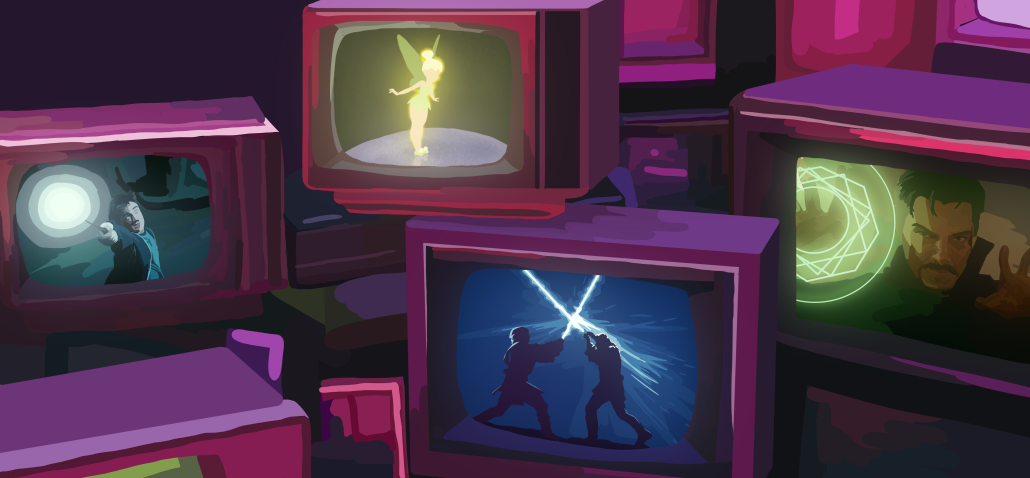

To illustrate, see “Star Wars,” “Harry Potter” (dubbed “The Wizarding World”) and the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the latter arguably laying the blueprint for how to continually engage a fanbase by spoon-feeding them seemingly endless spin-offs and crossovers.

The incentive of film sequels is obvious: a baked-in audience wanting to once again step into a universe it already loves, increasing the project’s chances of returning on investment and securing profits.

Many (yours truly included) love, and every other year revisit, classic millennial marathon-friendly franchises like Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings and The Hunger Games. But at what point does corporations leaning in to lure us back into these universes hamper the development of new, original ideas?

There’s a parallel here to the music industry, where samples and nostalgic references seem to have become a cornerstone of modern songwriting, and ongoing academic discussions are ripe about how popular music has become less complex.

The backdrop to all this is streaming: Gen Z is the first generation to grow up with not only its own generation’s music and film at its fingertips, but also all the classic music and film of the 20th century. The result? Current artists now compete with classic acts with budgets to boot.

In 2022, Per Sundin, former president of Universal Music Nordic, declared most record labels should make their brightest employees focus on catalog, rather than more recently released music.

In 2014, Mark Fisher, a former lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London, declared that “the future has disappeared” in a lecture titled “The Slow Cancellation of the Future.” He argues that the breakdown of social democratic policy, such as housing and unemployment benefits, have destroyed artists’ ability to contribute novel ideas to the culture: “The thing that has disappeared is a sense of difference … The sense of culture belonging to a specific moment, that is what has disappeared in the 21st century.”

Or maybe all the best songs and all the best stories have simply already been conceived?

There are, after all, only 12 notes in Western music, and most stories can be traced back to religious scripture. Corporations doubling down on a franchise strategy emboldened by 20th century nostalgia rooted in the malaise of our times certainly does not help. Neither do the financially cushioning incentives that come with it. Artificial intelligence, with its many potential implementations, is likely to bolster this backward-leaning approach to fresh culture.

Despite all the academic and commercial doomsday prophesying, as a passionate fan of film and music new and old, I am not worried. While it might be hard at this moment to imagine Harry Potter diminishing any of its massive popularity, or The Beatles somehow losing their reverence in favor of modern songwriters, I have faith in culture being inherently reactive.

I also believe creativity and originality prevails; history has proved that corporations, while having the clout to influence most cultural landscapes to a certain degree, are often helpless against creative ingenuity rooted in broader cultural shifts.

Every generation wants its heroes, and if repackaging and spinoffs — or global artists on billion-dollar grossing tours — define this era, expect original ideas and local artists to scratch the counter-cultural itch of Gen Alpha. Or maybe Gen Beta. Until then, let’s try to enjoy the nostalgia loop while it lasts.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our daily paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper daily (we are the only remaining college paper on the West Coast that prints every single weekday), independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: