‘The Monkey’ is a bloody, disjointed crowd-pleaser

The Stephen King adaptation is a gory joyride, although it may leave a little to be desired as a follow-up to Oz Perkins’ “Longlegs.”

3

The Stephen King adaptation is a gory joyride, although it may leave a little to be desired as a follow-up to Oz Perkins’ “Longlegs.”

3

Oz Perkins’ “The Monkey” solidifies the director as one of the strangest nepo babies in the industry today. Less than a year off his modern horror masterpiece, “Longlegs” (2024), and a decade after his directorial debut, “The Blackcoat’s Daughter” (2015), comes an incredibly strange horror comedy that appears to defy all of Perkins’ directorial past.

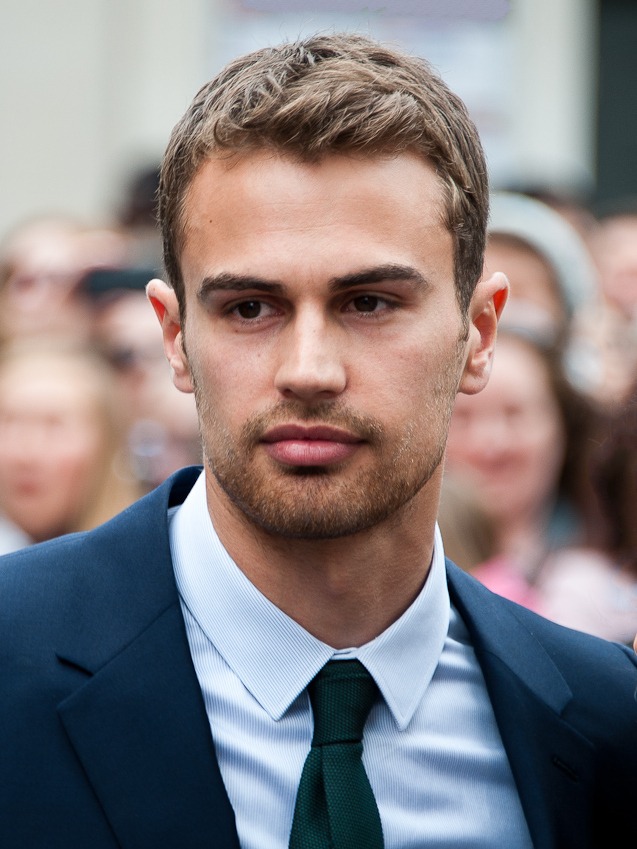

“The Monkey” follows twins Hal and Bill, both played by Christian Convery, who, as kids, discover and must deal with a wind-up monkey doll that mysteriously and indirectly kills a random person whenever its key is turned. Many years later, the monkey mysteriously returns and goes after a whole new slew of victims, and it is up to the now grown-up Hal and Bill, both played by Theo James, to discover what is happening and bring the massacre to an end.

Although Perkins has always stayed well within the horror genre, this film’s comedic and, frankly, quite light tone does not reflect any of his previous work. There are many successes within the film, such as stunning performances from the whole cast, and in particular James and Tatiana Maslany, and the phenomenal kills. However, there are other aspects, like the aforementioned tone as well as the themes of responsibility in the film, that ultimately result in a fun, but not very fulfilling, viewing experience.

James leads this film’s shockingly stacked cast twice over, once as Bill and once as Hal. While two roles by themselves would be impressive enough, the two characters are immensely different and move in completely different directions over the course of the film. Despite both characters looking exactly the same, it is easy to immediately identify which twin is which. Convery does a similarly spectacular job as the childhood versions of Bill and Hal, showcasing an up-and-coming talent that audiences should keep an eye out for.

Maslany meanwhile plays Hal and Bill’s mother and acts as the emotional heart of the film. There are several moments throughout that almost seem like they would’ve been cut if not for Maslany’s excellent performance.

Colin O’Brien closes out the main cast as Hal’s son Petey, and he shows a surprisingly large amount of depth despite the limited amount of screen time given to him. Smaller roles, such as Adam Scott as the twins’ father and Elijah Wood as Hal’s ex-wife’s new husband, round out the simultaneously hilarious and deep performances in the film.

The film is based on Stephen King’s short story “The Monkey,” and the original story is a standard King affair, a surreal mix of “Christine” and “It.”

Perkins’ adaptation, however, blows up the original short story in a spray of blood and viscera. King’s original story steps into overt violence very few times; the only death that even directly mentions blood is when a dog suffers an extremely traumatic hemorrhagic stroke — which is loosely adapted into the film, albeit not with a dog.

It is difficult to count exactly how many deaths are in the film, but there are probably 20 kills more gory and violent than the bloody death in the original by a significant margin. The kills are gruesome and creative. Due to the fact that the monkey is not able to attack directly, many of the deaths are set up like “Final Destination” lite, with elaborate setups that lead to the final, brutal kill. If audiences are coming to this film for the kills, they will get their money’s worth.

While “The Monkey” is a funny film, the humorous and direct tone does little to make it seem like the plot matters. Comedy is used as an occasional narrative sidetrack rather than half of the film’s genre profile. The humor is played cynically, and there are many scenes that feel anticlimactic as a result of focusing on humor rather than on the storytelling potential.

One of the biggest examples is the resolution of the primary conflict of the film. After it is discovered that Bill is responsible for the newest round of monkey-related deaths, he activates the monkey one final time. He makes amends with his twin and his nephew, and it seems to be building to a sweet resolution until a previously set-up cannon is ignited and blows Bill’s head off. It is a funny and shocking moment, but it works against the rest of the film. Humor is fine, but this film tends to use humor to the detriment of the plot.

The themes of the film are another place where the film falls apart. The original short story is a somber tale of grief, about the randomness of death and its inescapable existence. The monkey in that version is the physical manifestation of grief.

In the film adaptation, the heartfelt themes entrenched in why the villain works so well are replaced with ill-thought-out ideas of responsibility. The monkey’s randomness is replaced with intent by specific characters, making it less scary and much more annoying.

As opposed to the monkey’s presence in the original being built on terrifying randomness, the monkey in the adaptation is built on poorly established and single-dimensional motivations from the film’s characters.

The monkey is truly an icon of King, on the level of something like the Dark Tower or even Pennywise, and, in an attempt to put an explanation to the unexplainable, this film simply does not do that icon justice.

“The Monkey” is extremely entertaining and certainly worth a watch, although fans of the original short story or audiences looking for more than just a fantastically bloody film may find it lacking. It is not a bad film, and certainly not a waste of time, but it is doubtful to be a well-remembered inclusion in either Oz Perkins’ filmography or the larger canon of Stephen King adaptations.

We are the only independent newspaper here at USC, run at every level by students. That means we aren’t tied down by any other interests but those of readers like you: the students, faculty, staff and South Central residents that together make up the USC community.

Independence is a double-edged sword: We have a unique lens into the University’s actions and policies, and can hold powerful figures accountable when others cannot. But that also means our budget is severely limited. We’re already spread thin as we compensate the writers, photographers, artists, designers and editors whose incredible work you see in our paper; as we work to revamp and expand our digital presence, we now have additional staff making podcasts, videos, webpages, our first ever magazine and social media content, who are at risk of being unable to receive the support they deserve.

We are therefore indebted to readers like you, who, by supporting us, help keep our paper independent, free and widely accessible.

Please consider supporting us. Even $1 goes a long way in supporting our work; if you are able, you can also support us with monthly, or even annual, donations. Thank you.

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: