Roski masters students showcase dirt exhibit

Edible soil sounds like an unlikely concept. Though it is difficult to imagine the existence of such an abnormal idea, Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison made it (and tasted it) back in 1970 as part of their performance art piece Making Earth. Roski M.A. candidates Karen Hinchcliffe, Rachel Keller and Carly Warhaft have video proof.

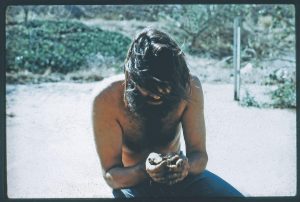

Photo courtesy of the Harrison Studio

Talk dirty to me · In Making Earth, one of the eco-art projects featured in the exhibit, a husband-wife duo make fertile soil using organic ingredients. The soil is edible and is part of the performance art piece.

Dirty Talk, an interactive exhibit curated by three M.A. candidates in Roski’s Curatorial Practices and the Public Sphere program, discusses Los Angeles’ soil ecology.

Making Earth is one of the works featured in Dirty Talk, an exhibition that opens Thursday at the Gayle and Ed Roski MFA Gallery just off Figueroa Street. Hinchcliffe, Keller and Warhaft, students in USC’s curatorial practices and the public sphere program, curated the gallery together as their capstone project.

Dirty Talk carves out a unique space even within the niche of eco-art galleries. During their preliminary research, the curators were drawn to the generation of eco-artists that includes the Harrison duo, and they had an insight that gave them a focus for their exhibit.

“[The Harrisons are] categorized as environmental artists, but they’re actually coming out of a historical lineage of performance.” In Making Earth, the Harrisons mixed topsoil, manure and other organic ingredients together in order to make dirt that was naturally fertile as well as edible. Tasting the final product was how they proved that the soil was healthy. But it was also a performative gesture, which invited the audience to consider how much they really knew about the chemistry of the soil their food grows in.

That’s a gesture that Hinchcliffe, Keller and Warhaft want to extend in Dirty Talk. In addition to commemorating Making Earth, and other historical eco-art projects by the Harrisons and conceptual artist Mel Chin, the Roski students have curated contemporary works in the same vein. All of the new pieces are by artists who live or have done extensive work in L.A., and all focus on local soil ecology. Their shared interest is in “shifting our understanding of Los Angeles as a place of nature,” as Keller put it.

Most importantly, every one of the works featured in Dirty Talk has an interactive or pedagogical component.

“We didn’t want it to just be a white box gallery show,” Keller said. “We hope that people come ready to engage, chat and talk critically about the works, and take things with them.”

For example, one work by the Commonstudio collective has visitors take home seed bombs – clay dolls peppered with hardy poppy seeds that can be planted in any soil. Another piece, a floor sculpture by Jenny Kane, contains a dozen samples of soil from different places in L.A. “How often do people walk on soil anymore?” Keller asked. “We’re hoping that people will take off their shoes and walk through this section of the gallery.”

Dirty Talk promises visitors an opportunity to physically engage with both the artwork presented and the issues the art takes on.

The curators are eager to make a difference with their gallery, not simply present the local history of eco-art.

“We talk a lot in the [MA] program about what we can do as curators,” Keller said. “What tools do we have that we can use in the cultural sphere to invoke or promote action or engagement in some way?”

The students’ retrospective approach is a forward-thinking curatorial strategy. Presenting historical eco-art performances by the Harrisons and Chin alongside contemporary pieces reminds visitors that environmental stewardship is a matter of legacy and tradition. When visitors leave the gallery, they’ll have something to take with them and ponder further. Keller suggested: “Take a seed bomb, and think about what it symbolizes.”

The gallery is located in the USC Graduate Fine Arts Building on 3001 S. Flower Street. Its hours are Wednesday through Saturday, 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Following the opening reception on Thursday evening, the exhibit will be open until Nov. 20. Admission is free.