Haring exhibit upholds accessibility, joy

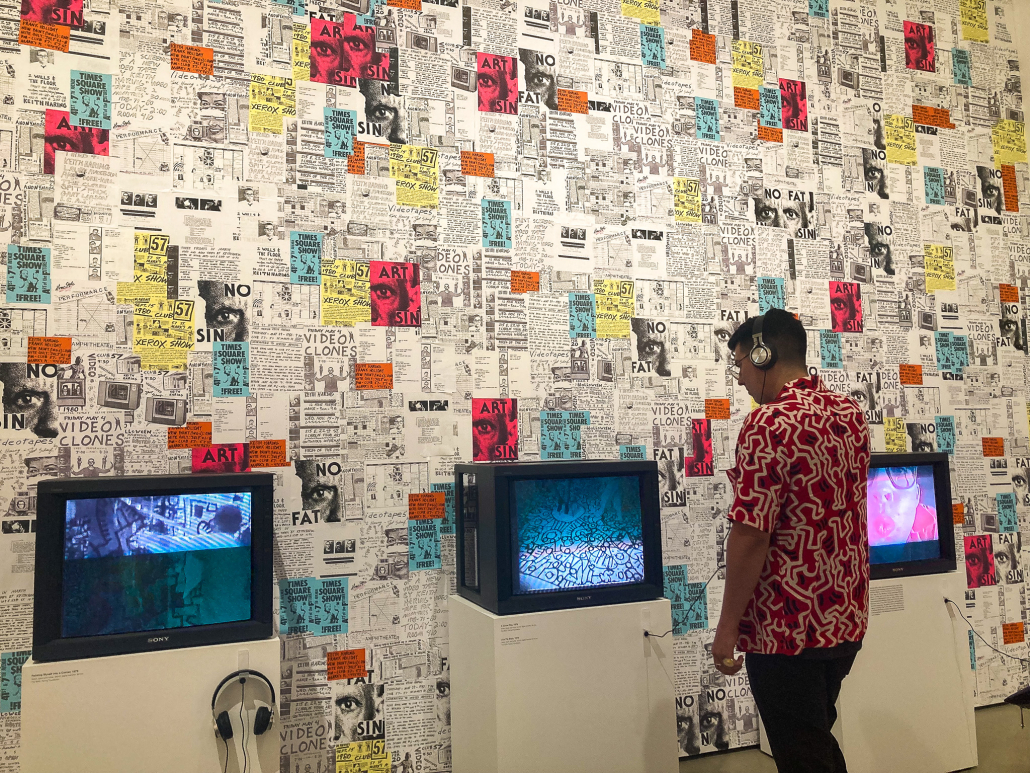

“Art is for Everybody” at the Broad pays homage to Keith Haring’s art and legacy.

“Art is for Everybody” at the Broad pays homage to Keith Haring’s art and legacy.

In 1980, a college student at the School of Visual Arts in New York City named Keith Haring began one of his first public art projects: daily chalk drawings on the unused advertising panels of the NYC subway system.

While Haring would soon become a household name for his lively murals and commercially-iconic figures like the radiant baby and barking dog, he also used his extensive platform to critique social issues of the 1980s. The Broad’s new exhibition, “Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody,” features 10 galleries spanning his life and prolific work, with art from 1978 to 1988.

The in-depth, interactive exhibit gives museum-goers insight into how Haring commented on the AIDS epidemic, apartheid, nuclear warfare, wealth inequality and police brutality while maintaining his instantly recognizable linework and vibrant style. From the very beginning of his career, Haring prioritized public advocacy through symbolic art.

“He really saw [the subway drawings] as a gift for the city. It was sort of an experimental project where he could develop his iconography,” said Sarah Loyer, the curator and exhibitions manager at the Broad Museum and the curator of “Art is for Everybody.” “He also saw them as ephemeral — someone could wipe their hand across it and smudge it and it could be gone. It was a way to create an imagery that was ambiguous and could cause people to stop and think, but also spread joy.”

Loyer began planning the show in 2019, traveling to the Keith Haring Foundation in NYC to do research. Many of the direct quotes on the walls of the exhibit, as well as its title, come from Haring’s journals, which have been published by the Foundation, to “bring his voice into the show.”

“I titled the show after a quote from his journal that he wrote when he was 20 years old … He had just arrived in New York, and he was responding to an art world that was pretty insular and not reaching the masses,” Loyer said. “He wanted to make work that was going to reach as many people as possible. Not only did he want that, he thought that was the responsibility of an artist. He really lived by that as a pillar of his practice.”

Loyer leaned into the biographical nature of the exhibit, interspersing Haring’s paintings with memorabilia such as Polaroid photos of him with friends and contemporaries, fliers he designed for the Chicago Voguers’ Ball benefit to support AIDS healthcare and a suit he painted for Madonna to wear at his “Party of Life” celebration. Collaboration was key to Haring’s process, and he worked closely with artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, LA II, Bill T. Jones and Grace Jones. NYC’s nightclub scene also helped foster community for Haring, and one gallery plays music from Haring’s mixtape collection of DJ sets, which he recorded live at clubs like Paradise Garage and the Palladium.

“Even though almost all of [his artwork] was made in the 1980s, it feels like it could have been painted yesterday,” Loyer said. “I wanted to have that same kind of feeling throughout the whole space, and I think the music helps make it feel alive.”

Kymia Freeman, a junior majoring in public relations, said the exhibit gave her a deeper understanding of Haring’s social justice work.

“Keith Haring, along with Jean-Michel Basquiat, are two really interesting examples of artists whose work started in one place and after their deaths have taken on a whole new life,” Freeman said. “Honestly, for a long time before actually seeing Keith Haring’s work in person, a lot of my conception around the art that he made came from a very commercial point of view. There are so many pieces of Keith Haring memorabilia, like T-shirts and bags in the world that the art can kind of get lost.”

Freeman particularly recalled one gallery that focused on Haring’s struggle with AIDS and his reaction to the epidemic and the lack of response and intervention from the government.

“A lot of the works in that part of the gallery were pretty well known, but seeing them right in front of my face was very emotional because I have done a decent amount of personal research into that period of American history and what role Keith Haring had in the advocacy around it,” Freeman said. “Seeing those works in person for the first time was really moving and just honestly represents a lot of what makes him such an incredible artist to me.”

Charlotte Bartel, a sophomore majoring in cinema and media studies, enjoyed seeing how Haring included various aspects of the LGBTQIA+ experience in his artwork.

“Near the end of the exhibit, he has these signs dedicated to being queer. My favorite one there is kind of simple, but it was one that he made when it was October, towards [National] Coming Out Day,” Bartel said. “A lot of the time when you have art [in museums] there’s not a lot of queer representation and expression.”

Haring’s acute ability to balance activism with joy through accessible art has played a profound role in solidifying his iconic legacy. His murals brought awareness to systemic issues of the 1980s that were rooted in bigotry and inequality, yet Haring created and shared them in a way that was digestible and vibrant.

“Anywhere he went, he would try to do a project that was in a public space, whether it was at a pool, or on the side of a building or in children’s hospitals, but really trying to find places where it was going to not only reach a lot of people, but also provide some sense of hope and optimism,” Loyer said. “Even though he’s addressing all these really difficult social and political realities, it’s always with a bright color palette and a dose of optimism. I think he really believed that art could change the world.”

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsDo Not AcceptWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them: