Gamification changes approach to software

No one, not even the late Steve Jobs, can say that they know everything about technology. Jobs might have come the closest to possessing knowledge about all things tech, but even he did not know every single programming language nor every startup in Silicon Valley.

The simple life · Your Extra Life gives users a false sense of accomplishment by rewarding users for incredibly simple tasks. – Sara Clayton | Daily Trojan

As a college student, tech is unavoidable. Apps such as Snapchat and Instagram play a significant role in today’s culture, and as a millennial, it’s fascinating to observe how tech is coming to shape our wired, Buzzfeed-loving society. In particular, gamification, which recreates the feeling of seeing your hard work pay off or being recognized, is a concept that is becoming normalized as our love affair with instant gratification continues.

Gamification is nothing new. In elementary school, it’s common for children to make games out of otherwise tedious tasks. Even in college, students are perhaps all too familiar with games such as king’s cup and beer pong, which add a gamified element to social drinking. In other words, “gamification” is an updated and digital-friendly version of such phrases as “positive reinforcement” and “extrinsic motivation.”

But these days, gamification stands out from these other ways of making tasks easier to complete because it is both simple to incorporate into non-gaming platforms and, best of all, cheap if not free to implement.

One example of gamification in action is Khan Academy. Khan Academy was founded by MIT graduate Salman Khan back in 2006, this nonprofit organization started out as a website featuring a collection of math lessons broadcasted through YouTube. But as the website continued to grow, so did Khan’s ambitions for his brainchild. After adding more topics to the site, in 2010, the Khan Academy team introduced six types of badges that users could earn by watching videos and solving problems. The more videos a user watches, the more objectives and badges he or she will achieve and, as a result, the more the user will learn.

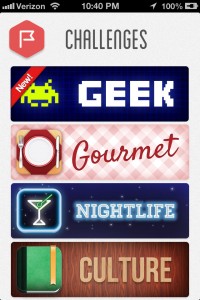

There’s also YourExtraLife, an iOS app that gamifies — yes — your life. The app isn’t as daunting as it sounds. Rather, it’s another way to keep you entertained and encourage you to break out of your comfort zone. In this app, there are several categories to choose from including “Geek,” “Culture” and “Romance.” Within these categories, there are challenges pertaining to each respective theme that must be completed in order to unlock more new challenges. With every challenge that gets completed, users move onto higher levels and are rewarded a variety of in-game nicknames.

For the most part, when various apps are interlaced with elements of gamification, the results are fairly successful (when executed well, that is). With 15 million registered users, Khan Academy boasts six million active monthly users — 40 percent of its overall user base. Apple’s Game Center, which serves as the archetype of gamification, has more than 240 million people connected. In addition to the previous examples, popular apps such as Nike Training Club also use this type of user retention model, pushing users to train harder in order to unlock extra workouts and badges.

Reaping real-life results from free and virtual rewards is effective in terms of cost and productivity. This all might sound too good to be true, though. And maybe it is.

Rewards in gamified apps and websites tend to be easier to achieve. While the reward after writing a 10-page essay tends to be a feeling of accomplishment or relief, when it comes to YourExtraLife, sometimes all one needs to do is take a photo or a screenshot to complete a challenge.

Though we’re not lab rats, it’s the exposure to these kinds of low-effort, high-reward scenarios that notoriously earned Generation Y the labels “lazy, entitled, selfish and shallow” by Joel Stein in a May issue of Time.

But as a member of this generation, this push towards gamifying just about everything might not be so much a reflection of millennials as it is a reflection of what has become of society in this day and age.

Because tech continues to get newer, faster and more advanced, our generation is becoming more difficult to satisfy. We never had to deal with massive computers or giant game consoles. We’re in an age where more than half of all adult Americans own smartphones and, on average, smartphone-users check their phones every 6.5 minutes.

While millennials are surrounded by so many other distractions, gamification is one way of capturing their attention. Call it entitlement, but it’s more like keeping up with the times.

It is sad, however, to think that the next generation of young people might always need something to keep them going. Be it Google Glass applications or robots that can encourage us based on what we’re doing, the next level of gamification is due – and it’s more than possible if it isn’t already underway.

Sara Clayton is a junior majoring in public relations.

Follow Sara Clayton on Twitter @saraclay15

At first I thought I found an article which criticizes gamification, which I would highly welcome in the current hype stage gamification is in. However, I miss the lack of understanding of the concept in this article: Even though I like that you highlight that gamification and its psychological origins from games is not new, restraining gamification to “positive reinforcement” and “extrinsic motivation” is simply a superficial act.

The concept of (proper) gamification goes far beyond feedback and extrinsic rewards, which may be overshadowed by the abundance of news articles and gamification implementations focusing solely on points, badges and leaderboards (PBL). Reinforcing intrinsic motivation, creating meaning through bigger goals or collaboration as well as designing a positive flow experience are just a few examples.

However, maybe this article can have a good influence on people by getting them thinking more deeply about the topic in order to design proper gamification. This means not to fall for the “quick and dirty” but predominant way of gamifying (PBL), which you described as the current stage.

Would love to discuss further:

@dmeusburger