Embracing the uncomfortable

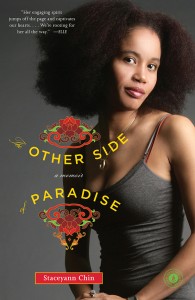

Femme fatale · Author Staceyann Chin recounts her past as a half-Jamaican, half-Chinese woman in her memoir, Other Side of Paradise. – Photo courtesy of Simon and Schuster

I often make people uncomfortable. Sometimes, it’s because I’m a hijab-wearing Muslim and that scares the Islamophobes. Sometimes, it’s because of how I write. People say I’m too intense, too feminist, too loud while trying to be heard. When I was younger, I viewed “too” as a negative word. It meant that I should be less of what I am so people don’t think I’m too much, so they think I’m just right.

But then I grew up and realized that I didn’twant to be just right — I didn’t want to be one of the many trying to fit in because in the so-called diverse land known as the United States, I will never be just another face. In the eyes of the public, I’m a criminal, and my rap sheet includes being a brown, loud, female Muslim with a moody temperament. And that’s OK.

As with most of my column so far, I take the long, rambling way to make a point. This week is no different.

The previous Thursday, after a long day of class and midterms, I attended the Survivor Speak Out event, which was part of the Woman Student Assembly’s Take Back the Night week. All I wanted was to go back to my dorm and repay my sleep debt, but I’d never been to Take Back the Night before, and my curiosity won out. My column had also come out that day, and I’d written about sexual assault, so I felt compelled to hear what sexual assault survivors thought of USC’s abysmal sexual assault and harassment rates.

The event took place at E.F. Hutton Park — that small, sloping space outside of old Annenberg. Many students were already gathered, spread out on blankets on the damp grass, holding electric candles in homage to those affected by sexual assault. A hush fell over the place, an almost sacred and unbreakable silence as we collectively held our breaths for what was to come.

Nothing could have prepared me for the emotional rollercoaster that took place. While the survivors who went on stage both broke my heart and made me outraged with their stories of sexual assault or partner violence, the keynote speaker resonated with me stronger than anything had that week.

Half-black, half-Chinese keynote speaker Staceyann Chin was an all-star. Although she was physically tiny, her personality took up the entire stage. Her voice was strong at times and soft at others, as she performed some of her poems and read excerpts from her book, The Other Side of Paradise.

Chin was abandoned by her mother as a child, and she didn’t know who her father was, only that he was Chinese. Her skin was lighter than that of the other children in Paradise, Jamaica, where she grew up, which earns her the status of “white girl.” She was also repeatedly sexually assaulted as a child — she describes her cousin’s sweaty hand making its way up her thigh with disgusting detail.

She spoke mostly in a loud, brash voice. She spoke about sex, masturbation and rape. She poked the audience until our timid answers were roars in the dark night, the space around us illuminated by the electric candles we held up high. She said “f-ck” a lot.

Chin made me uncomfortable.

In our little college bubble of privilege, it’s rare we’re made to feel uncomfortable. We may occasionally come across views we don’t agree with and people we don’t like, but we almost always are able to brush them off. Our lives are so privileged that we aren’t able to experience the feeling of being uncomfortable in our day-to- day lives, let alone go outside of our comfort zones. Although college is where we go to become full-fledged human upon graduation, it’s easy to remain unchanged in a campus as apolitical and sheltered as USC.

After the event, Chin’s voice was still ringing in my ears. I bought the Kindle version of The Other Side of Paradise because that uncomfortable feeling was mostly new, and I wanted to hold onto it.

Chin’s book is, as one reviewer calls it, “a captivating portrait of an artist as a young woman.” In it, she recounts every heartbreaking detail of her past.

Often memoirs are a mix of bravado and woe-is-me. Despite having had a terrible childhood, Chin’s memoir read like a competition of one-up-manship where the category is “worst life ever.” It’s a tragic book, yes, but Chin’s voice is consistently clear. She discusses race unabashedly and relays the dangers of being a young woman in a world where sexual violence is the easiest way to obtain power. Her resilience speaks through her words and is endlessly empowering and admirable.

Chin has always been a fighter. Everyone thought new born Chin, born several months premature, would barely live past her first week, let alone live long enough to write a memoir.

In her memoir, Chin writes: “It tickles me to think that from my very first breath, everyone expected me to stop breathing. Against the odds, I surprised everybody. And I must admit that in some of the moments of my life so far, no one has been more taken aback by my own breath than me.”

Noorhan Maamoon is a junior majoring in print and digital journalism. Her column, “The Hijabi Monologues,” runs on Thursdays.