Architecture lecturer finds justice through design

MASS Design Group executive director Michael Murphy spoke about the importance of integrating sustainability and ethical practices into architecture at the USC Wong Conference center Wednesday night. Accompanied by senior principal partner Kelly Doran, the two discussed how their nonprofit incorporates justice with beauty and creates carbon positive buildings that are the future of architecture.

MASS Design Group is a team of more than 120 architects, craftsman, researchers and artists who are reimagining the building process from design to construction. They prioritize using locally sourced, high quality wood, brick and tile to reduce environmental impact through the entire supply chain. This ensures that the project is durable and will last without the need for continual repairs that create waste and require more materials. They also focus on using ethical labor by hiring from within the community of a new building site, which ultimately facilitates long-term economic growth.

“MASS Design Group’s identity as a design firm is based on it’s assertion of having a mission to research, build and advocate for architecture that promotes justice and human dignity,” said Milton Curry, dean and professor at the School of Architecture.

Doran presented on the recent MASS project in Rwanda, which aims to build a new campus for the Rwanda Institute for Conservation Agriculture. The project exemplified the benefits and possibility of using locally sourced materials and labor for a large-scale project.

“The making of the building, aside from fasteners and tools, was entirely of the place and sourced 10 kilometers of the site,” Doran said. “Economically, this has a profound impact. The construction of this project is $250,000. Not a penny of that was spent on materials aside from a few nails and tools, so that all went into labor.”

The company uses local artisans for everything from bricks to lamps woven from banana leaves. One mason, Ahkiza from Rwanda, has supplied MASS Design group with his stonework for years.

“We’ve seen ongoing entrepreneurship emerge,” Murphy said. “We worked very closely with a series of masons and one of them is a gentleman by the name of Akiza. We still work with Ahkiza today, he has continued to do that same masonry work for 10 years with us and in doing so has started his own masonry guild.”

In addition to his efforts abroad, Murphy is implementing his vision of a more sustainable future in his hometown of Poughkeepsie, N.Y. The once thriving fringe city experienced a mid-century population decline, he said. Many buildings, which have been abandoned for decades, are now uninhabitable and most companies are not up to the task of restoring the city.

“When developers come to the city of Poughkeepsie at the end of a late market cycle, they inevitably find that the margins are too slim in order to invest and they give up,” Murphy said.

As a nonprofit, MASS works wherever they are needed. An office is now open in Poughkeepsie and many sites across the city have been preserved and refurbished to better serve the community, with some sites now serving as cultural centers, Murphy said.

When his team arrived in Poughkeepsie, it sought to repurpose abandoned spaces while still preserving the U.S. history that is frequently lost during urban renewal.

“This was an old garage which held the trolleys that went up and down Main Street — I had no idea what it was,” said Murphy, who did the design for free so that the project could get built. “But just pulling back that front door and seeing that it was this beautiful old piece of infrastructure, connecting with another nonprofit there, asked if it could be a new art and cultural space.”

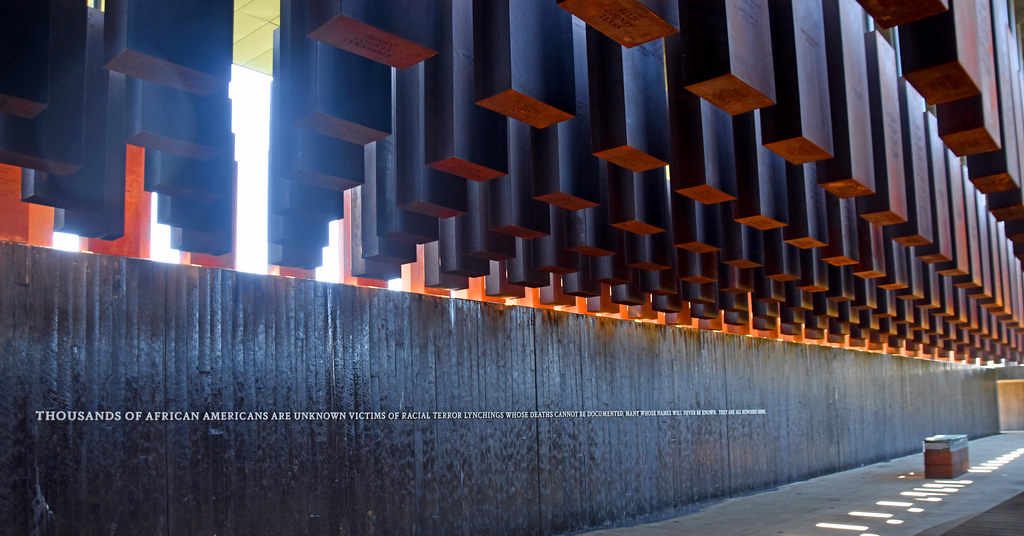

In addition to pursuing more ethical construction practices, MASS is committed to promoting social justice through their projects. The company designed and built the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., to recognize the ongoing impact of slavery and racial terror.

The monument consists of 800 steel tablets suspended from the ceiling, one for every county where lynching occured and each with the name of a victims and the date of their death.

“When you come up to it, you’re brought into this selective journey where you are forced to read and engage with the actual history of these places, by county, by name, by date,” Murphy said. “And then inquire, ‘Where are we?’”

The Gun Violence Memorial Project is another work of remembrance created by MASS. The memorial comprises four glass houses made of 700 bricks representing the 700 lives lost each week to gun violence in the United States. Within each brick is an object of significance from a victim of gun violence provided by the families. The memorial’s goal is to stop treating victims of gun violence as statistics or numbers and instead make it personal to show that each victim was an individual, precious life lost, according to MASS Design Group’s website.

The memorial originally debuted in the Chicago Cultural Center in September, and the reaction was so profound that Murphy decided that they had to continue expanding.

“It was amazing to see that this is an active, living memorialization process, one that gave us real hope that this could go to a larger scale,” Murphy said. “Could we continue collecting objects, fill thousands of these bricks and then take the project all over the country — one for every state, one for D.C., one for native lands — and put 52 of these on the National Mall?”

This integration of architecture and activism captivated the audience, which was made up primarily of USC architecture students. Devin Kidde, a junior majoring in architecture who has admired MASS and Michael Murphy’s mission for years, thinks that this sustainably focused design model is where the architecture business is heading.

“I saw his TED Talk when I was in high school, and it’s honestly the reason I decided to get into architecture school,” Kidde said. “I really hope that a lot of what he’s doing with taking a step back and looking at architecture as a nonprofit business design. I hope that that can take off in the future.”

Murphy, Doran and MASS know that they cannot change the world’s infrastructure alone, but they hope to act as a leading example of how others can change the world through whatever their medium may be.

“This emergence, this illumination, is a commitment to what I call the construction of dignity,” Murphy said. “That we have the possibility to do more with what we have in front of us.”