Virtual viewing hosted for the 50th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium

On Aug. 29, 1970, East Los Angeles was flooded by tens of thousands of young Mexican Americans part of the Chicano Movement. To commemorate the 50th anniversary of what is now known as the Chicano Moratorium, the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism on Aug. 29 hosted a virtual screening of the documentary “Rubén Salazar: Man in the Middle” and a live Q&A with a panel featuring filmmaker Phillip Rodriguez and leading Mexican American journalists, educators and activists.

The viewing was part of the Rubén Salazar/Chicano Moratorium campaign created by Rodriguez alongside media, community sponsors and educational partners. It seeks to encourage discussions surrounding bias and racial inequality in news coverage and how this event is significant to the Latinx community and its history.

Fifty years ago, following increased tensions between the Chicanx community and the Los Angeles Police Department, students and young activists alike took to the streets to protest the Vietnam War. Latino men were observed dying at a higher rate compared to the majority population in the war, making people in the Chicanx community concerned over the disproportional risk faced by Latinx soldiers.

These protests represent many different things for the Mexican American community in L.A. For one, it commemorates the tragic death of former Los Angeles Times reporter and KMEX news director Rubén Salazar.

Known for his news reporting on Latin America and the unrest in Mexico during the late 1960s, Salazar became further intertwined with the Chicanx community by joining KMEX, a Spanish language television station in L.A.

However, despite the Chicano Moratorium’s protests calling for the end of brutality toward Mexican Americans, Salazar was killed that day by LAPD Sheriff’s Deputy Thomas Wilson. Salazar had taken shelter after police released tear gas into Laguna Park and escalated violence at the protest. Wilson had fired tear gas into the Silver Dollar Cafe, where Salazar had taken refuge. While others in the building fled after the tear gas had entered the cafe, Salazar was fatally struck by the canister.

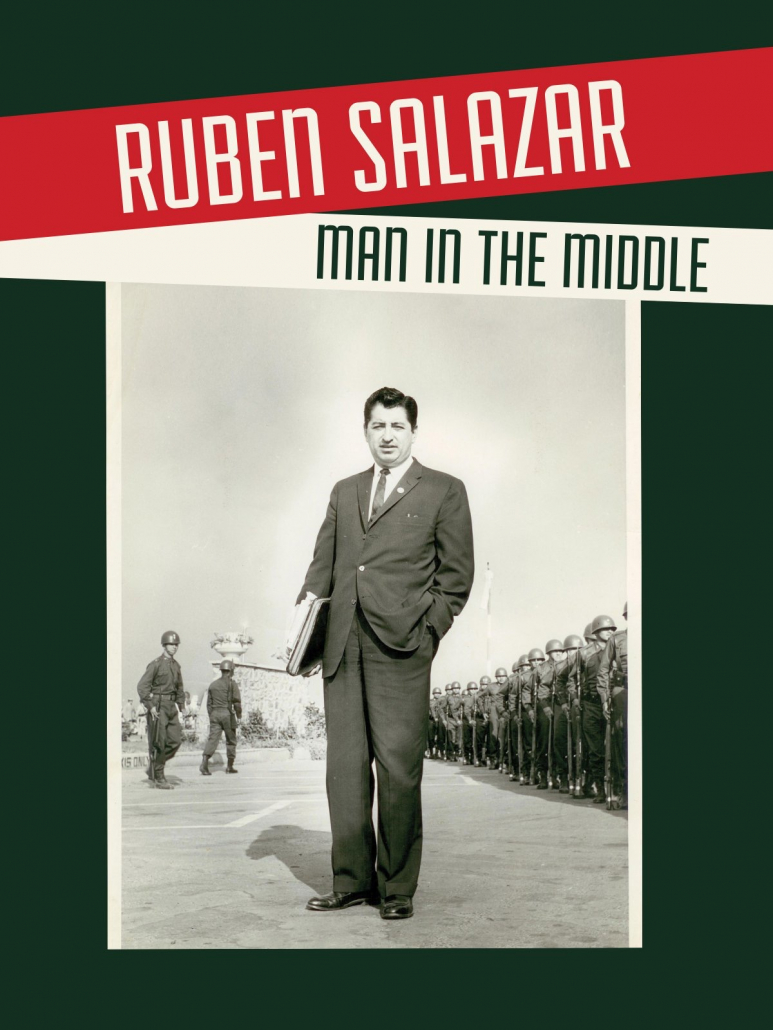

Salazar’s death sparked further protests and the legacy of his work is immortalized in the 2014 award-winning documentary “Rubén Salazar: Man in the Middle.”

The documentary showcases Salazar’s story, his Mexican heritage and transformation from a run-of-the-mill reporter to a staunch supporter and chronicler of the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 70s. It captures the enormous impact his life and death had on the Mexican American civil rights movement and modern social justice movements.

Rodriguez wanted to make “Rubén Salazar: Man in the Middle” because he saw something in Salazar’s story that piqued his curiosity, he said. He tried to dig deeper into mysterious circumstances surrounding Salazar’s death but soon found a more familiar story in the working-class man’s life.

“I set out to make a film certainly drawn by the glamour, by the noir, the glamour of his mysterious demise,” Rodriguez said. “But as I delve into it I realized he was a human being much like my parents, the silent generation of Mexican Americans, all but forgotten in terms of history and media product. I found a lot of appeal, glamour in his very ordinary, mid-century Mexican American identity.”

He also saw value in bringing to light the suspicious events surrounding Salazar’s death and what his passing represented for the community.

“I understood also I had an opportunity to bring up the facts of his death,” Rodriguez said. “It’s a bit of a paradox, that the big name that got killed at that event was not a Chicano American ‘rabble-rouser’ throwing a Molotov cocktail or an activist, but the middle-class guy.”

The 50th anniversary and its message for equality and the elimination of police brutality remain relevant amid the Black Lives Matter Movement, which has garnered mainstream media attention since the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and countless others.

Panelist and Los Angeles Times reporter Daniel Hernandez said, “From my observation, historically, Latinos have indeed often and frequently throughout history looked to African American models of resistance, we’ve looked to African American leaders.”

While the Black and Chicanx communities’ needs are not the same, each movement’s messages are intertwined in similar desires for increased protection and an end to systemic oppression.

“I think historically that there is a sense of deference and cooperation with Black leadership in the history of the United States,” Hernández said. “But I think there is opportunity to further advance the kinds of coalitions that have been taking place there, while also serving and focusing on the concentrations of each individual community as well.”

While the issues of oppression and racism that persisted in Salazar’s life exist now, many of those within the Chicanx community are looking toward the future for more ways to spread the demand for racial justice, which include diversity in media and reporting.

“I think what we can learn from the period of time in the ’70s, and specifically from Rubén Salazar, is that… we just need more voices,” panelist and co-founder of Mijente, an organization focused on providing political and social resources for the Latinx community, Neidi Dominguez said. “But we don’t have enough diverse voices to really reflect the impact that [coronavirus and police brutality] is having in our communities.”